"She had always wanted words, she loved them, grew up on them. Words gave her clarity, brought reason, shape. Whereas I thought words bent emotions like sticks in water." --Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient

|

|

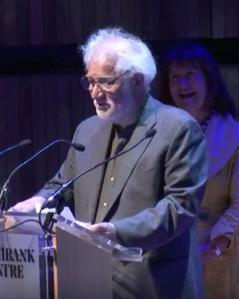

| Ondaatje accepting the Golden Booker. | |

When you learned this week that the Golden Man Booker Prize had gone to The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje, maybe you thought it was great news or maybe you thought of 50 other Booker winners who deserved the honor more.

Some folks considered the whole notion of a Golden Booker to be nonsense. Others suspected the popularity of Anthony Minghella's Oscar-winning film adaptation was the deciding factor, a theory Ondaatje himself didn't dispute. In his acceptance speech, he thanked Minghella, "who is no longer with us, but I suspect has something to do with the result of this vote." He also acknowledged "small presses everywhere," and cited authors--J.L. Carr, William Trevor, Barbara Pym, Penelope Fitzgerald, Alice Munro, Graham Swift, Samuel Selvon--who hadn't won a Booker but should have.

"Not for a second do I believe this is the best or most popular book on this list, or any other list that could have been put together of Booker novels," he said. "Especially when it is placed beside a work by V.S. Naipaul--one of the masters of our time, or a major work like Wolf Hall, or Penelope Lively’s beautiful Moon Tiger, or the heart-breaking Lincoln in the Bardo. I've not read The English Patient since it came out in 1992 and I suspect, and know more than any one, that it remains cloudy with errors and pacing."

While I admired his humility, I also wondered whether there's a point at which a book belongs to its readers as much as the author? When I learned that Ondaatje had won the Golden Man Booker Prize, I just smiled. Some books are more iconic than others, especially on a personal level. More than a quarter-century ago, The English Patient taught me--and still reminds me sometimes--how to be a better human being (a lot to ask of a novel, to be sure). It also, and this is no small matter, taught me how to become a bookseller and, specifically, a passionate handseller of books.

While I admired his humility, I also wondered whether there's a point at which a book belongs to its readers as much as the author? When I learned that Ondaatje had won the Golden Man Booker Prize, I just smiled. Some books are more iconic than others, especially on a personal level. More than a quarter-century ago, The English Patient taught me--and still reminds me sometimes--how to be a better human being (a lot to ask of a novel, to be sure). It also, and this is no small matter, taught me how to become a bookseller and, specifically, a passionate handseller of books.

Where do handsellers come from? "Everywhere" is the easy answer. The harder, though more precise, response is that they are often like gifted Dickensian orphans, waiting for someone to notice them. I can only tell you where one handseller came from, though I'd like to know your story, too, if you care to share it with me sometime.

I became a handseller in the fall of 1992. When I started working at the Northshire Bookstore in May of that year, I'd never heard the term. The first person who interviewed me explained that customers often came in looking for reading suggestions. In its simplest definition, a handseller was a bookseller adept at helping customers find those great reads.

Sometime during the middle of August in 1992, the same person who'd interviewed me placed an ARC of The English Patient in my hands and said, "I think you might like this." The novel was due to be published in a month or so. I fell in love with that book on first reading and every reading since. You know how it goes: rookie bookseller reads ARC, falls in biblio-love for the first time, and can't wait to talk about it.

Customer: "Have you read anything great lately?"

Me: "The English Patient."

"Could you recommend a cookbook for my mother?"

"Maybe she'd prefer The English Patient."

"My father hates novels."

"Oh, I think he'd like The English Patient.

"I'd like to return this book to exchange for something else."

"Have you read The English Patient?"

We sold the proverbial bejesus out of that book--well over 200 hardcover copies before it won the Booker Prize. I told my customers about the irresistible voice, characters, settings, as well as the fact that I could open to any page and read them an extraordinary sentence or paragraph. When they asked me to prove it, I did.

With that novel, I learned what it felt like to make an author's book my book. I learned that being a frontline bookseller mattered in a way that was fundamentally crucial to my life at the time. And I really haven't stopped handselling since, even as a longtime editor at Shelf Awareness.

I did, however, gradually learn that genuine handselling discussions actually begin with questions (ex.: What have you read lately that you love?) rather than fervent answers (You've got to read this!). And I realized that the art of conversation trumped the lesser art of evangelism every time.

In the film version of The English Patient, Count Almasy asks Hana why she is "so determined to keep me alive." Her response is at once spare and complex: "Because I'm a nurse." Handselling isn't about life or death, of course, but for most of us a life without reading is unimaginable (Because I'm a bookseller.). A little dramatic, but there it is.

From the novel: "She entered the story knowing she would emerge from it feeling she had been immersed in the lives of others, in plots that stretched back twenty years, her body full of sentences and moments, as if awakening from sleep with a heaviness caused by unremembered dreams."

The English Patient was an ARC I read in the summer of 1992. The story continues.