|

|

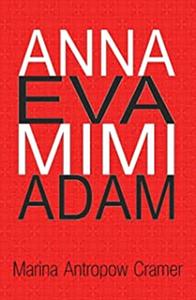

| Marina Antropow Cramer at Watchung Booksellers, Montclair, N.J., for last week's launch party for her new novel, Anna Eva Mimi Adam. | |

Born in postwar Germany into a family of Russian refugees, Marina Antropow Cramer has been a waitress, fabric store manager, traveling saleswoman, telephone fundraiser, used book dealer, business owner and bookseller. She holds a B.A. in English from Upsala College. Her work has appeared online in Blackbird, Istanbul Literary Review and Wilderness House Literary Review. She left bookselling in 2014 to focus on writing full-time, and now lives in New York's Hudson Valley. She is the author of the novels Roads, published by Chicago Review Press, and Anna Eva Mimi Adam, just released by Runamok Books.

My father, who lacked a formal university education, was a learned man. After the privations of the war years and with the refugee experience behind us, he filled our home in Paterson, New Jersey, with books--a steady stream of volumes bought with his laborer's salary, arranged on floor-to-ceiling shelves he built to house our growing library. Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev, Tolstoy shared space with Dickens, Shakespeare, Dumas, Jack London, Conan Doyle. Russian literary and scientific journals piled up in stacks on his side of the bed until my mother found room for them in the basement; to throw them away would have been unthinkable.

I was too young to read Doctor Zhivago when, in the 1950s, the phenomenon of its publication outside the Soviet Union became an international sensation. From the heated discussions around our kitchen table, I realized for the first time that literature was sometimes more than stimulating entertainment, that telling a story in a book of fiction could be political and treacherous. Pasternak's treatment was tempered by the approbation his work received in the free world, but not enough to lift the indignity of virtual house arrest or allow him to accept the Nobel Prize. Writing, I learned, could be an act of defiance, perceived as treason by those with the power to suppress the work and punish the author. I was old enough to become aware, even as a child, that reading could be more than a pleasant pastime. Books were not only delightful; they were important.

My father was pleased when I opened my bookshop, Cup & Chaucer Bookstore in Montclair, N.J., in 1985; it was almost as if his life's purpose in nurturing my mind had been fulfilled. For me, the work of acquiring inventory, stocking shelves, talking to people about reading, spending untold hours in the presence of books – all that came naturally, like an extension of the book-filled rooms of my growing years. To be a link, no matter how insignificant, in the chain that passes thoughts from one mind to the next, was intensely gratifying. I was, in my small way, a conduit for civilization.

My father was pleased when I opened my bookshop, Cup & Chaucer Bookstore in Montclair, N.J., in 1985; it was almost as if his life's purpose in nurturing my mind had been fulfilled. For me, the work of acquiring inventory, stocking shelves, talking to people about reading, spending untold hours in the presence of books – all that came naturally, like an extension of the book-filled rooms of my growing years. To be a link, no matter how insignificant, in the chain that passes thoughts from one mind to the next, was intensely gratifying. I was, in my small way, a conduit for civilization.

He encouraged my early writing, too, praised the effort even if the results were clumsy and naive. The many years of stops and starts, of abandoned projects, of putting story after story aside to take care of life's imperatives--much of this happened against the backdrop of being a bookseller. My shop was a constant reminder of what a writer could achieve with the necessary diligence, the vision made real through the application of time and work needed to add another book (mine) to the shelf.

Eventually, the shop closed, subject to economic realities and illness in the family. What would I do now? I was no longer young. I was committed to bookselling, not interested in a new career. I went to work in another bookstore, Watchung Booksellers, Montclair, N.J., doing tasks I knew and loved while staying connected to a vibrant reading community and beginning to recognize the shape of the book I needed to write.

It took a long time. Being in the bookselling world made it easy to meet other writers, to benefit from their experience and perspective. We formed feedback groups, met in each other's homes or in offices after hours, the space still resonant with the aura of the day's business; we sat together at restaurant tables, reading, talking, our pages surrounded by coffee cups and the occasional beer glass. I had to listen, to pay attention to criticism without falling back on self-justification. I started reading differently, too, with closer awareness of the craft, the use of writers' tools. What makes that sentence effective? How did the author elicit an emotional response from me, using those words? How is this story built? We studied each other's texts, relying on shared wisdom to move our own efforts toward clarity.

It was all immensely helpful, but not enough. To write this book, I needed the luxury of total focus without the distractions of job obligations. Writing had to be the main event, not an activity tucked into time left over from other schedules. I got my affairs in order and took the plunge. Within two and a half years, the research was completed, the manuscript finished, sold, edited, and published. I had earned a place on the bookstore shelf, if only for a little while.

I am not Boris Pasternak. I do not live in a society ruled by suspicion. My work does not have to demonstrate my loyalty to any political point of view, under penalty of persecution or exile. Nor is the story I tell meant to open the world's eyes to the harshness of a political system destructive of individual choice and happiness; the wages of tyranny are already well-documented. All I can hope is that it may cast a little light on ordinary people caught in bad times, doing their best to hold on to their humanity and stay alive. And that this may be, in its own way, important. Who knows?

My father did not live to see my work in print. I will never know how he would feel about the way I chose to tell the story of people like him--like us: the story of flight and displacement, of growing up too fast in a world filled with cruelty and constant danger, with chaos and hunger and death. Maybe he would approve my use of imagination in Roads, the things I added to fill out what I knew. Maybe not. But he would understand the desire, the passionate progression from reading child to bookseller to author. He would nod, and smile, and make us a cup of tea.