|

|

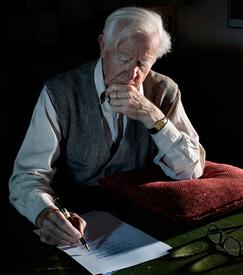

| John le Carré (photo:Nadav Kander) |

|

John le Carré, the master of Cold War spy novels that were thoughtful, densely plotted, elegantly written and explored ideology, history, language, and the interplay between politics and psychology, died on Saturday of pneumonia. He was 89.

His Cold War thrillers "elevated the spy novel to high art by presenting both Western and Soviet spies as morally compromised cogs in a rotten system full of treachery, betrayal and personal tragedy," the New York Times wrote. He "portrayed British intelligence operations as cesspools of ambiguity in which right and wrong are too close to call and in which it is rarely obvious whether the ends, even if the ends are clear, justify the means."

Born David Cornwell, le Carré worked in MI6, Britain's Secret Intelligence Service, and its domestic version, MI5, for 16 years. For a time he was a spy in West Germany, with the cover of a diplomat, running agents and more--all of which became fertile ground for his burgeoning career as a spy novel writer.

The best known of his more than two dozen books were set in Britain's MI6, "the Circus," forever at war with its Soviet counterpart, "Moscow Centre," with many of their battles played out in divided Germany. Most of the titles starred George Smiley, a taciturn, brilliant, methodical, dour, honorable, unassuming spymaster, betrayed by colleagues and his wife, and an aficionado of German literature and language; his Centre nemesis was Karla, who in many ways was more like Smiley than any other le Carré character.

Le Carré created a world in which, the Times wrote, "agents were 'joes,' operations involving seduction were 'honeytraps' and agents deeply embedded inside the enemy were 'moles,' a word he is credited with bringing into wide use if not inventing it. Such expressions were taken up by real British spies to describe their work, much as the Mafia absorbed the language of The Godfather into their mythology."

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, published in 1963 and le Carré's third novel, became an international bestseller, and was followed by, among others, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Honourable Schoolboy and Smiley's People, also known as the Karla Trilogy. One of Sir Alec Guinness's most memorable roles was as Smiley in the BBC TV miniseries of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) and Smiley's People (1982). Sadly for fans, le Carré said that Guinness played Smiley so well, taking over the character, that he could no longer write books featuring Smiley in the same way--and Smiley appeared only tangentially in several later books.

With the semi-retirement of the character Smiley and the end of the Cold War, le Carré developed new characters, set his books in different places, including Africa, post-Soviet Russia, and Central America, and investigated big pharma, money laundering and more. Among those titles were The Constant Gardener, Our Kind of Traitor, The Night Manager and The Tailor of Panama. In addition, The Little Drummer Girl, published in 1983, was, the Times wrote, "about an undercover operation by a passionate young actress-turned spy; the book performs the seemingly impossible trick of evoking genuine sympathy for both the Israeli and Palestinian points of view."

A Perfect Spy (1986), "le Carré's most autobiographical work, tells the story of Magnus Pym, a double agent with a con man father modeled after le Carré's own, and how the two deceive and are deceived by each other in an intricate skein of lies," the Times observed.

In later years, le Carré and his books became more straightforwardly political. He was vehemently against spy agency torture, the post-9/11 "war on terror" and Brexit. His most recent titles, both published in the U.S. by Viking, were The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life (2016), an autobiography, and Agent Running in the Field (2019), a spy thriller set in the world of the Circus in the present day.

Although le Carré refused to let his books be considered for literary awards, this year he accepted the Olof Palme Prize for his "extraordinary contribution to the necessary fight for freedom, democracy and social justice" and donated his $100,000 award to Médecins Sans Frontières. And in 2011, he accepted the Goethe Medal, given to non-Germans who "have performed outstanding service for the German language and international cultural dialogue."

As recounted by the Guardian, the Goethe Institut, which awards the Medal, said, "Fifty years after the Berlin Wall was built, 20 years after the end of the Soviet Union and 10 years after the terrorist attacks of 11 September, there could be no better moment than this to pay tribute to this extraordinary achievement of John le Carré with the Goethe Medal. Viewing language and knowledge of a country as a prerequisite for penetrating world history and understanding ideologies, religions and peoples--these are the aspects that characterise the life's work of John le Carré.... His novels, whose themes revolve around the contrasts between east and west and the cold war, captivate the reader with their painstaking psychological depiction of the characters and their wealth of historical details. Le Carré broke with stereotypical viewpoints and criticised the betrayal of western ideals."

The Goethe Institut also called le Carré "Great Britain's most famous German speaker" and said he "has always been convinced that language learning is the key to understanding foreign cultures."

Speaking at a Think German conference in 2010, the Guardian noted, le Carré said that for most of his "conscious childhood Germany had been the rogue elephant in the drawing room. Germans were murderous fellows. They had bombed one of my schools (which I did not entirely take amiss); they had bombed my grandparents' tennis court, which was very serious, and I was terrified of them. But in my rebellious adolescent state, a country that had been so thoroughly bad was also by definition worth examining. Also, one of the few things I had enjoyed about my schooling had been the German language, with which my tongue had formed a natural, friendly relationship."