Once upon a time (the summer of 2005, to be precise, just two years before Kurt Vonnegut's death), a slender book with a provocative title--A Man Without a Country (Seven Stories Press)--gained what the publishing industry likes to call "traction." It was written by a great American author.

Once upon a time (the summer of 2005, to be precise, just two years before Kurt Vonnegut's death), a slender book with a provocative title--A Man Without a Country (Seven Stories Press)--gained what the publishing industry likes to call "traction." It was written by a great American author.

During the early 1970s, like thousands of others, I "discovered" Slaughterhouse-Five, and continued reading Vonnegut for several years until I just... wandered away. ("So it goes.") Inspired by A Man Without a Country, I returned to his books again, but with the perspective of a much older Earthling. His hard-won wisdom and sense of humor seemed even sharper and more relevant.

A Man Without a Country is a study in justifiable anger, generously spiced with compassion and humor. Consider the answer Vonnegut once gave a woman asking for his advice about bringing a child into this terrifying world: "I replied that what made being alive almost worthwhile for me, besides music, was all the saints I met, who could be anywhere. By saints I meant people who behaved decently in a strikingly indecent society."

Or this: "But I have to say this in defense of humankind: In no matter what era in history, including the Garden of Eden, everybody just got here."

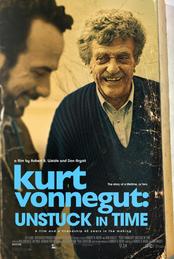

As it happens, I was rereading A Man Without a Country when I learned about the new IFC documentary Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time (in theaters and VOD). Directed by Emmy winner Robert R. Weide and Don Argott, the film chronicles the brilliant, wise and complicated author's better-than-fiction life story. It also opens a window on his unlikely but deep 25-year friendship with Weide, who filmed Vonnegut over the course of two decades, then spent a long, long time reaching the point where he could put the film together.

The reasons for this are complex and addressed beautifully in Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, which spans the author's childhood in Indanapolis; his experiences as a WWII prisoner of war in Dresden before and after the horrific firebombing in 1945; his complicated family life; his early careers as a publicist for General Electric and a car salesman; and his long years as a struggling writer before a bolt of fame hit him with the 1969 publication of Slaughterhouse-Five.

|

|

| Robert Weide and Kurt Vonnegut in Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, courtesy of C. Minnick and B Plus Prods. An IFC Films release. | |

This amazing film project really began when Weide was a teenager. "I discovered him like most readers did, in high school," he recalled. "My English teacher was pretty hip. Her name was Valerie Stevenson and she was only in her 20s herself, and she assigned us Breakfast of Champions. It changed my life. I always want to acknowledge the role that she played, which would make Kurt happy because he was constantly talking about how teachers are so undervalued. They really serve the most important job in a democracy, he always said, and we treat them like dirt."

Several years after first reading Vonnegut's books, Weide, now a 23-year-old aspiring filmmaker, wrote a letter to his literary idol proposing a documentary on the author's life and work. To his surprise, he received a handwritten response in which Vonnegut said, "Anything that is any good of mine is on a printed page, not film," but also gave his blessing and a phone number, inviting Weide to call. Shooting began in 1988 and continued intermittently until the author's death in 2007.

|

|

| Kurt Vonnegut in Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, courtesy of C. Minnick and B Plus Prods. An IFC Films release. | |

Nearly four decades would ultimately pass, however, from Weide's first reading of Slaughter-House Five until he was ready to literally and figuratively unpack all the footage and accompanying memories. The result is deeply compelling. Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time is time travel at its best. As Vonnegut and Weide age on screen, their personal and professional lives alter, as lives do. Filmmaker and subject become close friends ("family" to use Vonnegut's word).

|

|

| Robert Weide (photo credit: Colin Hutton) | |

Weide, whose portrait of Vonnegut is a candid one, observed that "there is certainly pain and loss in his life and in his work, so it was inevitable that this melancholy would come through in the film. In his books, sometimes it's text, sometimes it's subtext. But the beauty of his work is the cliché that he's got you crying one minute and laughing the next. The humor and the tragedy, and the blend between the two make up a very distinct part of his voice.... [This film] should also leave the viewer feeling like he or she just spent two hours with one of the funniest, smartest, most creative people they could ever hope to meet."

Vonnegut remains a significant presence in the life of Weide and his wife: "A day never goes by where he doesn't come up in conversation," the filmmaker observed. "Also, his artwork is all over our house, and we still use the candlesticks that he got for our wedding as our Shabbat candles every Friday night. We also practice Kurt's suggestion that during happy moments in your life, you should say out loud, 'If this isn't nice, what is?' It's all just a continual reminder as to how much this guy has impacted my life."

The line is in A Man Without A Country, too, when Vonnegut recalls his late Uncle Alex's ability to appreciate being in the moment. I could say the same about Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time: "If this isn't nice, I don't know what is."