|

|

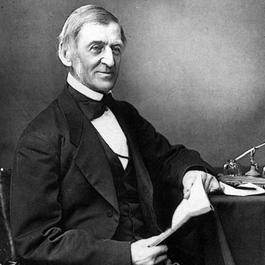

| Ralph Waldo Emerson | |

I hate quotations. Tell me what you know.

--Ralph Waldo Emerson

Inspiring quotations are as traditional a way to start the new year as champagne toasts and resolutions. So let me quote author Ben Ehrenreich, from a 2013 Los Angeles Times New Year's Eve item: "My literary resolutions are always the same: Read more, write more, and when otherwise unoccupied, read and write more." Sound advice.

I've been thinking about quotations this week because of something Fast Company sent in one of its Compass e-newsletters for the new year--a link to an archived 2018 piece headlined: "You've been misquoting these inspiring phrases your whole life." This pertinent question was asked: "Do all those inspirational quotes we see for #MotivationMonday or #WisdomWednesday really exist? And were they really said by the people we are so quick to believe said them? Yes and no."

Example: Do not follow where the path may lead. Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail. Forbes contributor Maseena Ziegler had earlier pointed out that the lines were often misattributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson online, but Muriel Strode actually wrote them in her 1903 poem "Wind-Wafted Wild Flowers," which opens: "I will not follow where the path may lead, but I will go where there is/ no path, and I will leave a trail."

Ziegler also explained that an academic periodical reprinted Strode's slightly revised quote (replacing just the I's) with a credit to Emerson. "Not long after, it appeared as a sign at a school once again incorrectly credited--and from there you could say it took off."

Despite Emerson's previously mentioned antipathy to quoting and the Internet's flawed essence, I love quotations and have long been a devoted "bracketer" (private quoting, you might call it) when I read. If I pull a book at random from my shelves and idly flip through the pages without seeing the title, I know immediately if it's a work I liked due to the number of sentences or paragraphs set off by brackets. Purists and serious book collectors may be appalled by the way I deface the books I love most, but I'm a collector, too. I collect from inside the book.

Here's the last sentence I bracketed, just yesterday, in Amanda Lohrey's brilliant novel The Labyrinth: "This was my unlikely beginning: in the midst of madness I had been happy."

Bracketing is probably my version of a commonplace book. It's also a mnemonic sometimes, sparking memories beyond the page. For example, take this book I just pulled from my shelves--Emerson: The Mind on Fire (U. of California Press, 1995) by the late Robert D. Richardson. (Okay, I cheated a little there because I did reach for it intentionally.)

Bracketing is probably my version of a commonplace book. It's also a mnemonic sometimes, sparking memories beyond the page. For example, take this book I just pulled from my shelves--Emerson: The Mind on Fire (U. of California Press, 1995) by the late Robert D. Richardson. (Okay, I cheated a little there because I did reach for it intentionally.)

Flipping through the pages, I'm reminded that Richardson came to the bookstore where I was working at the time for an author event. I had the privilege of introducing him and he signed my copy. So did legendary artist Barry Moser, who created the jacket illustration and attended this reading, but steadfastly declined to autograph a copy of the book until the author had signed it first, which impressed me.

Since that night, I've added my own marks in the form of bracketed passages. Now it's my story, too. Here's some Richardson that brought out my pen while I was reading:

[Emerson wrote]: "Learn how to tell from the beginnings of the chapters and from glimpses of the sentences whether you need to read them entirely through. So turn page after page, keeping the writer's thoughts before you, but not tarrying with him, until he has brought you the thing you are in search of. But recollect, you only read to start your own team."

The last point is crucial. Reading was not an end in itself for Emerson. He read like a hawk sliding on the wind over a marsh, alert for what he could use. He read to nourish and stimulate his own thought, and he carried this so far as to recommend that one stop reading if one finds oneself becoming engrossed.

Sounds like a bracketer to me. By the way, Emerson didn't really hate quotations. He quoted other writers all the time. He also wrote: "By necessity & by proclivity, & by delight, we all quote.... The quoter's selection honors & celebrates the author. The quoter gives more fame than he receives aid."

So quoting him seems like a good way to end this column and begin 2022: On January 4, 1827, Emerson wrote in his journal: "A new year has opened its bitter cold eye upon me... & found my best hopes set aside, my projects all suspended. A new year has found me perchance no more fit to die than the last. But the eye of the mind has at least grown richer in its hoard of observations. It has detected some more of the darkling lines that connect past events to the present, and the present to the future."