It is ridiculous for one man to set himself up to decide what people shall read and shall not read. It would be an attempt to impose his temperamental and intellectual limitations on the general public. The reading public is the best judge of whether a book is moral or immoral.

--Sir Gilbert Parker, in a New York Times item headlined "Against Censoring Books" (September 8, 1922)

With self-appointed book vice squads ever mustering across the U.S., Banned Books Week focuses public attention on a year-round challenge (think whack-a-mole but with censors) by celebrating the hard work being done to confront pernicious Booksnatchers.

But what if we turned the clock back a hundred years; if we read the New York Times in September 1922. What might a comparable bookish news cycle look like?

|

|

| John Saxton Sumner | |

Well, on September 13, 1922, the Times reported that, in a decision by Magistrate George W. Simpson in the Municipal Term Court, a charge made by John S. Sumner, secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, against publisher Thomas Seltzer was dismissed and Seltzer discharged. Also exonerated was Mary H. Mark, a circulation library employee, charged by Sumner with loaning, for a consideration, one of three books involved in the case.

The titles on trial were A Young Woman's Diary, attributed to a Viennese girl between the ages of 11 and 15; Women in Love by D.H. Lawrence, described by the magistrate in his decision as a book in which "the author attempted to discover the motivating power of life"; and Casanova's Home-coming by Dr. Arthur Schnitzler, referred to by the magistrate as "a leading man of letters" whose book was "the story of the last love affair in his declining years of one Casanova, famous for his memoirs."

.jpg) "Books will not be banned by law, merely because they do not serve a useful purpose nor teach any moral lesson," Magistrate Simpson said, adding: "I have read with sedulous care Casanova's Home-coming, Women in Love and A Young Girl's Diary. Following the tests laid down by the cases in this state, both as to the manner of judging publications and as to the meaning of the statutes, I do not find anything in these books which may be considered obscene. On the contrary, I find that each of them is a distinct contribution to the literature of the present day. Each of the books deals with one or another of the phases of present thought."

"Books will not be banned by law, merely because they do not serve a useful purpose nor teach any moral lesson," Magistrate Simpson said, adding: "I have read with sedulous care Casanova's Home-coming, Women in Love and A Young Girl's Diary. Following the tests laid down by the cases in this state, both as to the manner of judging publications and as to the meaning of the statutes, I do not find anything in these books which may be considered obscene. On the contrary, I find that each of them is a distinct contribution to the literature of the present day. Each of the books deals with one or another of the phases of present thought."

Seltzer commented: "The people have shown clearly that they recognize the menace of literary censorship, and they have served notice on Mr. Sumner that they will not tolerate dictatorship of what books they may read and what books they may not read. They have the right to choose the reading matter for themselves and they mean to exercise that right.... The American People, I am sure, will soon find a legal way to put a stop to it.... I do not consider this my victory alone; it is the victory of the entire reading public."

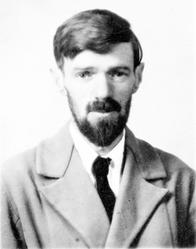

|

|

| D.H. Lawrence | |

Noting that "you can't win every case," Sumner was not disheartened by the loss, stating: "It is simply a case of his opinion differing from the opinion existing here and on the part of the people who called out attention to these books." Having confiscated many copies of the books he found in Seltzer's Manhattan office, Sumner was ordered to return them.

A day later, a commentary in the Times noted that "Sumner comes near to giving his case away. If there may be difference of opinion among intelligent and decent people about the morals of a given book, the Vice Society is going to find its field of uselessness restricted to something like its original objects. Luckily, the Court's opinion prevails; we are not yet, as it seemed not long ago we would be, in bondage to those members of the Vice Society whose minds were most avid and acute to scent evil where none existed."

By September 17, a lawsuit for damages of $10,000 had been filed against Sumner by Jonah J. Goldstein on behalf of Seltzer on the grounds of false arrest and injury to his business. A similar suit was to be filed soon on behalf of the employee.

But Sumner sprang up like a weed again later in the article, saying: "We have not this year obtained any convictions for the publication of indecent books, but we did last year. Although some publishers succeed in winning the cases against them, the chances of being convicted and the fact that others have been convicted is the chief deterrent against a flood of still more vicious books than we have today."

![]() He quickly took another loss, however. On September 28, the Times reported that Magistrate Charles S. Oberwager had dismissed Sumner's case against Boni & Liveright, Inc. for publishing The Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter.

He quickly took another loss, however. On September 28, the Times reported that Magistrate Charles S. Oberwager had dismissed Sumner's case against Boni & Liveright, Inc. for publishing The Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter.

"The legislature did not intend to confer on any individual or society general powers of censorship over literary works," the magistrate observed, "for if such were the case the power could easily be abused and the destruction of freedom of speech as well as freedom of the press would be the resultant effects of such a statute.... One who is not content with repressing scandalous excesses, but demands austere piety will soon discover that not only has the rendering of an impossible service to the cause of virtue been attempted, but that vice has thereby been added."