Short answer: ∞/1.

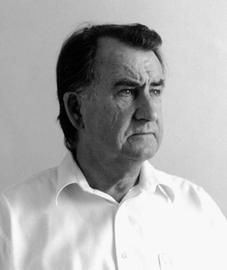

A gracious loser, however, I congratulate Annie Ernaux on her well-deserved honor and can now confess that my money was on a longshot: Australian writer Gerald Murnane, whose 2022 Nobel Prize for Literature bookies' odds coming down the homestretch were running around the 30/1 mark.

|

|

| Gerald Murnane | |

That number was consistent with his Nobel odds back in 2006, when he told the Age, "It's a bit better odds than this drought will break." He was not surprised to be on the list then ("I was given to believe some months ago that I had been nominated. It wasn't by an Australian. It was almost certainly from someone in Sweden."), but wouldn't be flying to Stockholm should he win ("My reason is that my whole life is built around a reluctance to travel.").

Why Murnane? Well, for the past couple of months I've been on a reader's winning streak with his books. At one point in the early stages, I found myself simultaneously enthralled by The Plains (hardcover), Last Letter to a Reader (paperback), Tamarisk Row (e-book) and Border Districts (audiobook). This was crazy-making, of course.

Another, not quite so noble, reason for gambling on Murnane could be chalked up to the fact that his work and life are infused with horse racing: bookmakers' odds, punters' "can't fail" systems, owners' "can't lose" colts; bets won or--more often--lost. Even as a child, he would arrange "my glass marbles on the lounge-room mat or my chips of stone on my pretend-racecourse under the lilac bush" to run imaginary races. Variations on these memories often pop up in his tales.

After the Nobel Lit Prize results were announced yesterday, London's Kirkdale Bookshop tweeted: "Gerald Murnane is looking wistfully at his collection of marbles round about now. In his mind, countless real and imaginary horse races are occurring simultaneously."

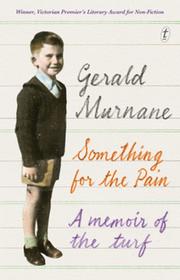

In Something for the Pain: A Memoir of the Turf, Murnane writes: "I've always believed the odds to be too much against me. And yet, I still today continue the research that I began as a boy more than 60 years ago; I still spend a few minutes each morning checking the results of the latest betting system that I've devised."

In Something for the Pain: A Memoir of the Turf, Murnane writes: "I've always believed the odds to be too much against me. And yet, I still today continue the research that I began as a boy more than 60 years ago; I still spend a few minutes each morning checking the results of the latest betting system that I've devised."

He also recalls: "I knew better than to expect much money from the sales of my books of literary fiction, but I hoped to earn a modest income from betting--yes, betting on racehorses. Despite my father's dismal record and my own lack of success in earlier years, I still believed I could beat the odds."

In the Nobel Lit Stakes, however, Murnane has remained a longshot, if one with solid form. On Tuesday, the Guardian reported that Salman Rushdie, victim of a horrific stabbing in August, was the bookies' favorite at 13/2, with Michel Houellebecq and Annie Ernaux ("last year's bookmaker's favorite") at 5/1, followed by Anne Carson (4/1), Haruki Murakami (12/1), Margaret Atwood (9/1) and Stephen King (17/1).

But in the Atlantic on Wednesday, Alex Shephard wrote that predicting the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature "is a fool's errand. I should know: For the past seven years, I've tried to guess the winner based on odds from the British sportsbook Ladbrokes and never once gotten it right.... Despite this track record, I continue to make predictions about the prize. Why? Two reasons. One is that it's a fun, low-stakes way to engage with the literary world, which most people take way too seriously. And the other is that it remains the single best global survey of literature."

He touted five authors who had never won the prize, and "they probably won't win this year. But their names keep coming up for a reason: They have, over the past several decades, built up an astonishing and influential body of work."

One of the five was Annie Ernaux; another was Gerald Murnane. "Four years ago, the New York Times's Mark Binelli wrote that 'a strong case could be made for Murnane, who recently turned 79, as the greatest living English-language writer most people have never heard of,' " Shephard noted, adding that the author "is admittedly a bit of an eccentric, and culturally remote. He lives in the middle of nowhere in Australia: Goroke, Victoria, population about 300, where... he occasionally tends bar and hangs out at the local men's shed (a kind of state-run cultural center aimed at reducing loneliness among the elderly). All of this makes Murnane fun to talk about, but he is also an extraordinary writer."

How did Murnane take another Nobel loss? Quite well, I suspect. "I was bemused by what I had learned about myself that day," he writes in Something for the Pain. "I seemed to have a built-in regulator that would not allow me to bet more than a certain amount. I might have said that whenever I stepped onto a race course my arms became short and my pockets deep."

And... there's always the next race.