On Veterans Day, I think of my father, who landed on Utah Beach in August 1944 with the 243rd Field Artillery Battalion. He died at 50, taking his memories with him. He was a quiet man, so I had to read him as best I could, mostly between the lines.

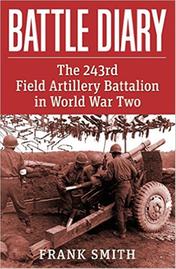

There's one book, however, that does connect me to the 23-year-old poor kid from Castleton, Vt., who'd been working for the Vermont Marble Co. in a quarry before he was drafted. Captain Frank Smith's Battle Diary: The 243rd Field Artillery Battalion in World War Two was self-published in 1946, and a copy sent to everyone in the battalion, with their names and home addresses listed in an index. It's really an edited version of daily after action reports. I've read it many times.

There's one book, however, that does connect me to the 23-year-old poor kid from Castleton, Vt., who'd been working for the Vermont Marble Co. in a quarry before he was drafted. Captain Frank Smith's Battle Diary: The 243rd Field Artillery Battalion in World War Two was self-published in 1946, and a copy sent to everyone in the battalion, with their names and home addresses listed in an index. It's really an edited version of daily after action reports. I've read it many times.

My father didn't talk about his war, but in Battle Diary I can follow his shadow as he slogged across France to Germany. When I first approached the book many years ago, I was cautious, assuming it was the enemy before gradually discovering an ally. That's what books can sometimes do.

Battle Diary is about time passing dangerously, within the deceptive context of daily routines, like this: "14 March 1945--Six rounds of 170 mm slammed into B's number 1 gun position at around 2400 last night. All men were in the cellar except the guard on the piece, who quickly dropped into a spade pit. One round hit only eight yards away, tearing holes into five rounds of ammunition but leaving him unhurt." My mother, at some point, scribbled "your father" on the page, with an arrow pointing to the entry. My anonymous old man, under fire.

He would have turned 102 years old October 29 if he hadn't died July 17, 1971. This means he has been gone from my life longer than he was in it, which is one way of reading time. Marble is another, its geological history mocking human timekeepers. Had my father been a superhero in one of the comics I read, he would've been called Marbleman, defying time like stone. But he wasn't, and time won that battle handily.

If someone saw real action during World War II, they generally didn't talk about it much. When I was a kid, we knew those vets in town. They scared and intrigued us.

Any details I have about his war come from the scattered paperwork he left behind. For example, I can read a form that tells me he was in the Army for 38 months, rose to the rank of Private First Class. He was a Cannoneer, Heavy Artillery. His job description: "As a crew member of an eight-inch gun using separate loading ammunition, assisted in moving, emplacing, firing, and withdrawing the piece in combat operations. Set up and fired gun, assisted in such maintenance as cleaning and oiling of gun. Performed these duties for 17 months overseas."

Overseas is a pleasant word that, in this context, has deadly implications, including battles in Northern France, the Rhineland, Ardennes and Central Europe. He was awarded Good Conduct and Victory medals. He did his job, came back home, and went down into one of the quarries again, before eventually being transferred to the finishing shop in Proctor.

|

|

| Worker's punch clock, Vermont Marble Co. office, circa 1870. | |

Later in his life he worked in the Vermont Marble Co.'s machine shop, where he would eventually earn a promotion to the position of timekeeper, a job he never explained to us beyond the fact that it had something to do with calculating payroll, with punch clocks and, well, with keeping time for other workers.

My father wasn't much of a book reader, but he made an exception for anything about General George S. Patton, who, as it happens, had been a voracious reader. His biographer, Martin Blumenson, observed in Patton: The Man Behind the Legend, 1885-1945 (1985) that "he jumped from vulgarity to scholarship as nimbly as a cat."

In Battle Diary, I read: "Upon arrival in England the battalion was informed that it was assigned to the Third Army, commanded by the already fabulous George S. Patton, Jr., and then marshalling for movement into France for a decisive strike against the Germans." Later, Smith notes: "As Patton's Army moved from the Moselle to the Saar, all three batteries of the 243rd followed closely behind the doughboys and tanks."

My father had been just another small-town boy captured in his natural habitat and released into the organized chaos of a monumental and terrifying moment in world history. Patton once wrote: "The most vital quality a soldier can possess is self-confidence, utter, complete and bumptious." Hard for me to think of my father that way. An unlikely pair, those two, and yet one of the last books I recall my father reading was Ladislas Farago's Patton: Ordeal and Triumph (1964).

At the Vermont Marble Museum in Proctor, there are blown-up, grainy photographs depicting early 20th-century marble workers posing down in the quarries, or beside their gang saws, or shielding their eyes from sun reflecting off marble slabs in the yards. All of them stare grimly at the camera, as if to say: You done yet? We got work to do. They could be soldiers; some probably were.

The museum also has an exhibit depicting the origin story for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Vermont Marble Co. workers quarried, sawed and fabricated those blocks, then delivered them by rail to Arlington National Cemetery in 1931 to be assembled and finished.

The museum also has an exhibit depicting the origin story for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Vermont Marble Co. workers quarried, sawed and fabricated those blocks, then delivered them by rail to Arlington National Cemetery in 1931 to be assembled and finished.

Just thinking about the complexity of that word--unknown. Hard man to read, my father.