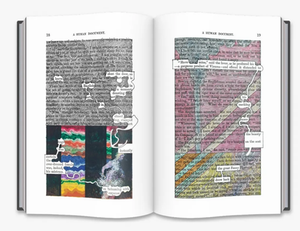

Imagine an artist's book that is also a reader's book. A Humument lures its readers into an intoxicating world of color and form, wit and intellect, love and lust. The art delights. The words intrigue. The combination astonishes.

|

|

| Tom Phillips | |

These were the opening lines of a 2004 piece I wrote for Tin House magazine's "Lost & Found" series, condensed from my graduate lecture at Bennington College in 2003. The art of Tom Phillips, especially A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel, had had an immediate and profound impact on me that has only grown deeper with time.

Phillips died November 28. He was 85. A Guardian obit in the art section, some social media posts, and a couple of art magazine notices appeared. His passing has otherwise seemed oddly unremarked upon, though his publisher, Thames & Hudson, tweeted: "We are saddened to learn of the passing of Tom Phillips. Our team had the pleasure of being involved with the 50th anniversary edition of his A Humument, a 'defining masterpiece of postmodernism.' He will be dearly missed by all those who knew him."

If ever there was a bookish artist, it was Tom Phillips. I'd originally "discovered" his work through a turn-of-the-century obsession with the painter R.B. Kitaj, another artist whose love of language infused his creations.

"As usual on a Saturday morning, R.B. Kitaj and I prowled the huge warehouse in search of bargains. Arriving at the racks of dusty books left over from house clearances, I boasted that the first one I found that cost threepence I would make serve a serious long-term project. I soon chanced on a yellow book with the tempting title A Human Document. Looking inside we saw the fateful price. 'If it's a dime,' said Ron, 'that's your book: and I'm your witness.' "

Over the next five decades, Phillips continued to acquire copies of W.H. Mallock's 19th-century novel and "treat" its pages with his art, leaving selected words from the original text exposed to craft an illustrated, "dispersed narrative" (as he described it) in verse, "with more than one possible order." The new tale was of a man named Bill Toge, who wallows hopelessly in love and lust for Irma, the ever-elusive woman of his dreams. Irma reprises her role from the original novel, though the story spins away in many directions over subsequent editions.

"I have so far extracted from this book well over a thousand segments of poetry and prose and have yet to find a situation, a sentiment or thought which his words cannot be adapted to cover," Phillips wrote. "That Mallock and I were destined to collaborate across a century became quite clear when I tested other fictions and discovered nothing to equal him in the provocation of fresh conflations and conjunctions of word and phrase."

To focus only on A Humument, however, is to do Phillips an injustice as an artist. You can happily find his works online, and it is a rabbit hole worth falling down. On the other hand, he was a man of letters, reading English Literature and Anglo Saxon at St Catherine's College, Oxford. As recently as 2017, he was named to the panel of judges for the Man Booker Prize, with the Guardian describing him as "a polymath" who had painted Iris Murdoch and collaborated with filmmaker Peter Greenway on a TV series based on Dante's Inferno. A love for words and literature infuses his art ("After Henry James," "Curriculum Vitae," "Samuel Beckett").

Phillips once observed that he loved "the smell of a library and the feel of books. Most of all I love the serendipity and the aleatory quirks of browsing.... Every book, however unpromising, will turn out to have its day." I like to imagine someone, a century from now, sifting through a tumbled pile of dusty books in a back alley shop and coming upon a battered copy of A Humument.

He finally tracked down Mallock's grave in 1990, and that treated image concludes the final edition, along with these words: "dedication--/ TO THE SOLE AND ONLY BEGETTER OF THIS VOLUME/ by whose bones my bones my best, perpetuate/ your grave in mine fused/ page for page/ THE END."