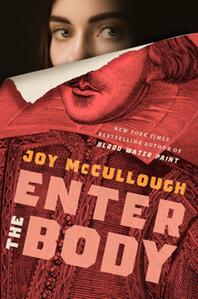

Joy McCullough (Blood Water Paint) pays homage to William Shakespeare, whom she admires for how he "took established stories and made them his own." McCullough, in turn, commendably retells the Bard's tragedies in fiercely feminist examinations of Romeo & Juliet, Hamlet and Titus Andronicus, built into an overarching plot that gives the plays' female characters a chance to tell their own stories.

Joy McCullough (Blood Water Paint) pays homage to William Shakespeare, whom she admires for how he "took established stories and made them his own." McCullough, in turn, commendably retells the Bard's tragedies in fiercely feminist examinations of Romeo & Juliet, Hamlet and Titus Andronicus, built into an overarching plot that gives the plays' female characters a chance to tell their own stories.

Enter the Body is divided into three parts. Part One begins in the trap room, a large open space beneath a theater's stage that acts as a "purgatory" for those who "die" onstage. Nineteen-year-old Lavinia, 17-year-old Cordelia, 15-year-old Ophelia and 13-year-old Juliet reside here, among others. Juliet tells the story of her forbidden love, a "spark ignited when palm met palm/ and turned to raging inferno that threatened/ to incinerate the world." Ophelia jumps in to relieve Juliet from her tragic tale and describes how she'd "been used/ and humiliated/ by these men." Next is Cordelia, "who made a sacrifice born out of love" only to be disowned by her father. One character whose story is not told but who is equally important--if not more so--is Titus Andronicus's Lavinia. Lavinia, with her tongue cut out and her hands cut off so she couldn't reveal the vile acts that had been done to her, represents the women who can't tell their stories, whether out of fear or death. She's instead a "silent observer," a witness to the other women's pain and vulnerability as they recount being subjected to male power and authority. Most of Lavinia's thoughts are shared in the sections of prose that are woven throughout the novel-in-verse. These sections are also welcome periods of pause, reflection and commentary, conveying what the other women in the room are thinking and feeling.

Part Two is written as dialogue in a play, with the women analyzing their stories and discussing Shakespeare's misogynistic choices, including making women mad or evil for convenience's sake and using their dead bodies as props. Juliet is fed up with the way things have always been done and challenges the women to tell their story as they would have liked it to play out. As a result, in Part Three, each woman shares her ideal version while the others provide astute and droll commentary. A poetic and entrancing tribute to the women of Shakespeare. --Lana Barnes, freelance reviewer and proofreader

Shelf Talker: This entrancing, fiercely feminist examination of William Shakespeare's tragedies gives his female characters the opportunity to tell their own stories.