It is universally known that there are books compos'd without any strength of genius, which appear quite insipid and unaffecting to the reader, and only tire the eyes; but those that are compos'd with an exquisite force of ideas, and with an exact connexion of thought, elevate the foul, and fatigue it with the very pleasure, which, the more compleat, lasting, and frequent it is, breaks the man the more.

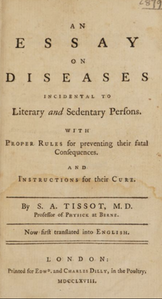

--An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Literary and Sedentary Persons by Samuel-Auguste Tissot, M.D. (1768, London)

What's the perfect book gift for the person on your list who's trying to ban every book they encounter for any reason that occurs to them? A former bookseller (once a bookseller, always a bookseller), I still read with that little voice in the back of my head wondering: Who could I handsell this to? Book banners seem like an ideal target for the title cited above. Keep 'em guessing.

As a book banning Fahrenheit 451 wildfire continues to spread across parts of the U.S. that will remain anonymous to protect their lack of innocence (including states we'll code name FL and TX), I recently found myself entranced by a 250-year-old work that has everything you'd want to read if you were intent on never reading again. Comps? Let's say Edgar Allan Poe co-authoring a self-help medical book with Dr. Oz. A work at once terrifying, nausea-inducing, absurd, and boundlessly overconfident.

|

|

| Samuel-Auguste Tissot, by Angelika Kauffmann, 1783 | |

The full title of Tissot's aberrant treatise (long-term side effects still to be determined) is An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Literary and Sedentary Persons with proper Rules for Preventing Their Fatal Consequences and Instructions for their Cure. The author was a notable 18th-century Swiss physician once praised by Napoleon and apparently best known for Avis au peuple sur sa santé (1761) and L'Onanisme (1760).

A Facebook post by The Public Domain Review clued me in, linking to a copy of Tissot's essay. "It was dangerous to be a man of letters in the eighteenth century," PDR noted. "All that rumination; such single-minded concentration; countless hours hunched over the escritoire. 'Some men are by nature insatiable in drinking wine, others are born cormorants of books,' wrote the Swiss physician Samuel-Auguste Tissot.... As with the reckless consumer of claret, an overindulgence in books could have devastating consequences for the mind and body."

Tissot offers hundreds of "examples of men who read too much, studied too hard, and consumed knowledge to the point of madness," including the young man who developed an allergy to reading ("if he read even a few pages, he was torn with convulsions of the muscles of the head and face, which assumed the appearance of ropes stretched very tight") and another whose intense focus affected hair retention ("his beard fell first, then his eye-lashes, then his eye-brows, then the hair on his head, and finally all the hairs of his body"). Then there's the guy experiencing "dreadful palpitations" while reading Descartes' Treatise on Man, and the one who "fainted away whilst he was perusing some of the sublime passages of Homer."

Edging into Poe territory, Tissot diagnosed "the blind Constantius Huygens, whose 'immoderate studies so broke the force of his sensorium, that he thought his body was made of butter.' Huygens found himself very cold, shunning the fire 'lest it should melt him,' and tragically ended his life by leaping into a well. And there 'have been many instances of persons, who thought themselves metamorphosed into lanterns, and who complained of having lost their thighs,' " PDR wrote, adding that some of Tissot's prescriptions have modern relevance in our era of "dopamine fasting" and "digital detoxes." Paging Dr. Oz.

Edging into Poe territory, Tissot diagnosed "the blind Constantius Huygens, whose 'immoderate studies so broke the force of his sensorium, that he thought his body was made of butter.' Huygens found himself very cold, shunning the fire 'lest it should melt him,' and tragically ended his life by leaping into a well. And there 'have been many instances of persons, who thought themselves metamorphosed into lanterns, and who complained of having lost their thighs,' " PDR wrote, adding that some of Tissot's prescriptions have modern relevance in our era of "dopamine fasting" and "digital detoxes." Paging Dr. Oz.

Given the curious obsession of contemporary book banners with removing excellent rather than bad books from libraries, it's interesting to note that Tissot believed the best writers were potentially more damaging to a reader's health. According to PDR, "Unlike later moral panics about the corrupting effects of fiction on female readers, here it is paradoxically the most praiseworthy material that produces the most lamentable results."

After pages of cautionary and sometimes odious medical detail (for studious men, "a perpetual dissipation of the nervous fluid springs from the incessant action of the nerves."), it's curious that Tissot ends his treatise on a relatively upbeat note: "Cheerfulness of temper is the source of health, and a virtuous life is the source of cheerfulness: a good conscience, a mind pure and clear of all contagion, all the best preservatives of health; and if the learned were without them, it would be a shame: for of what use is learning without wisdom?" I guess everybody loves a happy ending.

-Doctor, it hurts when I read An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Literary and Sedentary Persons.

-Well then, stop reading! Give it to the book banners. At least you'll confuse them.