|

|

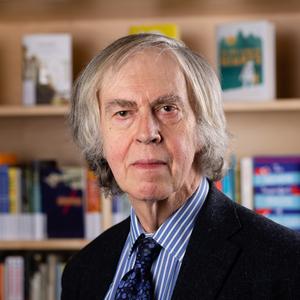

| photo: Michael Jershov | |

Charles Palliser's The Quincunx was awarded the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction by the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, which is given for the best first novel published in North America, and it has sold more than a million copies internationally since its publication in 1990. His other novels include The Sensationist, Betrayals, The Unburied, and Rustication. His new novel, Sufferance (Guernica Editions, May 1, 2024), is a deeply unsettling psychological story set in Eastern Europe during World War II.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

In a country under occupation, a man offers shelter to a young girl of a different faith. Gradually it becomes clear that he has put his family in grave danger.

On your nightstand now:

I'm reading Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh, which is the most astonishing and gripping first-person account of an old woman recalling her appalling relationship with her disgusting alcoholic father. She describes how, at 24, she was working in a boys' prison in the mid-'60s when she became obsessed with a glamorous new female counselor there. Explosive consequences follow from that situation. You gradually realize that the narrator is on the edge of insanity and probably has a personality disorder. Her anger at the people around her is matched only by her self-disgust. The novel is compellingly horrible.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I first read The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien when I was 11, and I read it again every few years. Very few writers have achieved the narrative drive of that trilogy which keeps you gripped through hundreds of pages and numerous intertwined stories. It's hardly an exaggeration to say that Tolkien invented almost everything in fantasy that has been worth doing since his time.

Your top five authors:

Saul Bellow's fiction made a powerful impact on me in my late teens: the wit, the comedy, the invention of a language that could soar from the street-gutter to the heights of speculative thought inside a sentence. Herzog is one of the greatest novels of the last 60 years.

Kurt Vonnegut showed me how much you can achieve by writing in almost the opposite way to Bellow: laconic, stripped down, darkly ironic.

I find it astonishing that Bernard Malamud, writing in the '50s and '60s, is not better known now. The Fixer and The Assistant are immensely powerful and moving novels in which he explores with extraordinary insight the mystery of human emotions in all their bewildering complexity.

Carson McCullers is a giant of the novel. Is there a better study of early adolescence than the girl, Frankie, in The Member of the Wedding? Her transition from child to teenager is captured with understanding and sympathy--but with irony, too, as the reader sees and understands much more about adulthood than she can, even as she longs to enter the world of grownups on which she spies. McCullers's work is deeply concerned with "outsidership"--with people being or feeling excluded from what they see as a more rewarding form of life. Her work is deeply compassionate and never remotely sentimental.

Jane Austen is the novelist I reread most often. Her work, however familiar, is always fresh and I think that's because of the wit of the dialogue, the steady focus on the motives and values of her characters, and the pared-down elegance of her prose.

Book you've faked reading:

I never got far into James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. In my defense I will say that, on the other hand, I came to know and love his Ulysses, which, though far more accessible, is still not an easy read.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Lanark by the late Glasgow writer and artist Alasdair Gray is an astonishing masterpiece. It's about--among so many other things--the struggle of a creative person against both an environment hostile to the arts and also against his own inner demons that threaten to drive him into madness and violence.

Book you've bought for the cover:

I once bought a copy of Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White because it had an extraordinarily haunting and evocative painting on the cover that depicted a big old house at night with only a few windows lit up. I already owned another edition of that book and it's one of my favorites. I bought that copy for the cover, which was a painting by the underrated Victorian artist John Atkinson Grimshaw.

Book you hid from your parents:

At 13, I got access to a copy of the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley's Lover by D.H. Lawrence, which had just been published for the first time.

Book that changed your life:

I read Franz Kafka's The Castle at 16, and it showed me how deeply into your unconscious a novel can lodge. The narrative turns the reader into a dreamer in the way the setting and the events and the mysteries and obstructions that baffle and frustrate the central character have the strange logic of a dream in which what is happening is, on one level, absurd and irrational and yet, at the same time, has a deeper meaningfulness that is the logic of the unconscious.

Favorite line from a book:

In Jane Austen's Emma the heroine says to her father: "One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other." So true!

Five books you'll never part with:

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad, The White Hotel by D.M. Thomas, The Music of Chance by Paul Auster, and The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose: a vivid imagining of life in a medieval monastery and an intriguing murder-mystery.