|

|

| Robert Fieseler (photo: Annie Flanagan) |

|

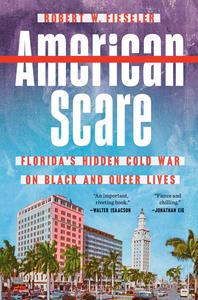

Robert W. Fieseler is a journalist investigating marginalized groups and a scholar excavating forgotten histories. He was named 2019 Journalist of the Year by the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association and received a Pulitzer Traveling Fellowship. His first book, Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation, won seven awards, including an Edgar for Best Fact Crime. Fieseler's second book, American Scare: Florida's Hidden Cold War on Black and Queer Lives (Dutton), is a riveting examination of a state-sponsored campaign of surveillance and intimidation. The following excerpt is from the preface.

It's as if the forces of justice and karma break and break upon the shores of Florida. From the swords of colonizers to the whips of overseers to the dynamite of Klansmen to the attack dogs of police, the land has acted as a New World Eden for strivers with oppressive dreams. It's a place where power plays beyond ordinary rules and where some folks get away with everything.

It was September 4, 2021. Hurricane Ida, a Category 4 storm, had made landfall several days prior. In the trunk of my rental van was sufficient evidence, twenty‐some bankers boxes of historical documents, to deliver to what I believed would be a mortal reckoning on Florida and its past. I knew I had to get these materials across state lines even if that meant hiding them in my storm‐ravaged city.

Hurricane Ida walloped the Gulf Coast on August 29, and it downed the power lines to my hometown of New Orleans, which sweltered without electricity in the peak of midsummer. I was in Chicago when the storm alerts hit my phone, and I had to book a hotel reservation on the fly in northern Mississippi for my husband and our two kittens, who immediately evacuated our house. Ordinarily, I'd have hopped a flight to join my displaced family. But my husband assured me from a Red Roof Inn that he was fine and the kitties settled, and I'd made a promise to someone in Tallahassee, Florida. It was an unusual promise (a spiritual boon for a historian in my position), a promise that I'd willingly accept a gift, that I'd take something unique off someone else's hands. And on that promise hinged an entire history at risk of vanishing.

I couldn't forget what Bonnie Stark, the first Johns Committee scholar, told me when we spoke that first time via video chat two weeks prior: "There are maybe twenty boxes of the papers. And I have them. Because the gentleman for the legislature who was overseeing the release of the papers, he came to appreciate how hard I was working, and when they finally transferred everything to the Florida Archives, he gave me the hard copies. And I've lugged these around forever. Right now, they're in my office at work."

Bonnie Stark possessed something that shouldn't exist. She held the secret second set of the complete records of the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (FLIC), also called the Johns Committee--a forgotten cabal of gerrymandered white legislators that went after Black and queer citizens in the mid‐twentieth century at the height of anti‐Communist hysteria. In the Johns Committee's path of destruction lay the freedoms of the masterminds of Florida desegregation, plus the lives and careers of more than thirty preeminent scholars, at least seventy‐one teachers, and as many as five hundred college students, whose persecution led all the way to the steps of the state supreme court and the U.S. Supreme Court. The crusades of these Florida men and their nearly decade‐long reign had all but vanished from the American story, the records sealed and then censored upon release. Names of victims were deleted by agents of the state who never had to say sorry. After all, why say sorry to a ghost?

Bonnie Stark possessed something that shouldn't exist. She held the secret second set of the complete records of the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (FLIC), also called the Johns Committee--a forgotten cabal of gerrymandered white legislators that went after Black and queer citizens in the mid‐twentieth century at the height of anti‐Communist hysteria. In the Johns Committee's path of destruction lay the freedoms of the masterminds of Florida desegregation, plus the lives and careers of more than thirty preeminent scholars, at least seventy‐one teachers, and as many as five hundred college students, whose persecution led all the way to the steps of the state supreme court and the U.S. Supreme Court. The crusades of these Florida men and their nearly decade‐long reign had all but vanished from the American story, the records sealed and then censored upon release. Names of victims were deleted by agents of the state who never had to say sorry. After all, why say sorry to a ghost?

The State of Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis's Florida, labored under the belief that it possessed the only surviving copies of FLIC records under lock and key. In a land of supposed sunshine laws, state authorities hid their histories in plain sight in the Soviet pillbox-like structure of the Florida State Archives, where the establishment could monitor who accessed them and obstruct the curious few with burdensome procedures and policies. "When you get power in Florida," state senator Lauren Book forewarned me, "you can use it to pick on anyone." In a Gulf borderland where administrations become regimes on a dime, people out of power tend to get hurt.

I knew I had to move this cargo out of Florida before state authorities caught wind of what Bonnie Stark had stashed and how I planned to use it. Within the official State Archives, I was permitted to review only one redacted page per one folder at a time, while sitting in one specific seat that directly faced the desks of watching bureaucrats, who could snatch things away on impulse. With all the files at my disposal, documents could be analyzed and cross‐referenced from first page to last. Duplicates could be compared, instead of culled, with redaction mistakes noted and leveraged to recover knowledge. De‐censorship would be possible. Power had lynched history, but by an unforeseeable twist, it could be restored. Then we, the people, might finally sit with the story they didn't want us to read.

On September 4, I loaded up box after box in the parking lot of Bonnie Stark's legal office. She had kept the records to herself for nearly thirty years, to the point that it shocked her mentor to learn of them, and then she entrusted them to a veritable stranger. What did that feel like for her? I detected relief in her eyes as she watched them leave her sight. Later, I worked up the courage to ask her. "I remember thinking I have to help him," she said. "I felt a kinship to you, that we shared a common appreciation for the importance." I peeled out of Florida's capital city. Who am I to inherit such a quest, I asked myself, such a gift as this life's work? And to what extent did my whiteness or my maleness or my middle‐class upbringing somehow set me up to receive a lucky break out of a clear blue sky? How am I different from any other outsider who appropriates a people's history and then explains it back to them without shame?

Overwhelmed with impostor syndrome, I thought about turning around as I neared the tip of the Panhandle. As I crossed a bridge above a bay, my questions spun in the other direction. Aren't any Floridians besides Bonnie Stark even curious why, once a decade, an anti‐queer or anti‐Black movement will sprout from their soil, flourish, and spread its seeds across America in a panic that inevitably claims that tough action will save innocent whites from a moral hellscape? Why, to privilege a sunshine dream, are generation after generation of Florida strongmen allowed to escape culpability? How could one peninsula be such a pressure point for the American body politic, such a wavemaker for the nerves?

I possessed a hefty part of the answer in the back seat of my van. Although Florida didn't invent the American Scare, the strain of fear sown by the Johns Committee blooms first here before heading elsewhere. Yet I was still in Florida's jurisdiction, and I had the wildest thought that Governor DeSantis himself would be waiting at the border in his duck boots and blue fleece vest--standing with hand outstretched before a highway blockade. But nothing ridiculous like that happened.

I exhaled a short breath regardless as I passed the inverse "Welcome to Florida" signage and crossed state lines. Hours later, I entered the balmy cover of New Orleans, a metropolitan region asleep in shadowy quiet. Streetlights stretched overhead like the arms of sheltering saints. As I arrived at my shotgun house, neighbors sat gossiping and clinking beers on a nearby stoop. They rose to high‐five and greet me with their storm stories.

Politely declining offers of help, I off‐loaded the boxes by candlelight into my living room, which looked unfamiliar in the yellow glow. Then I blew out the lights, one by one, like a man from another time. The history they tried to kill has survived, I affirmed as I waited for my eyes to adjust. And someone in authority miscalculated terribly, I realized as I looked over the trove of evidence. You can't half kill the truth. Not in America, where it'll only play dead, go dormant for years, and resurface to tell its story of being buried. "No lie can live forever," preached the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in his final Sunday sermon before a nobody shot him in Memphis.

We are a nation where self‐evident truth outlives power, and not even pharaohs can carry their lies with them when they close their eyes to meet the same eternal rest as paupers. I tried to grab a few hours' rest before heading north to reunite with my displaced family. In my dreams, a man with no face redacted the Constitution in the name of public safety.

Excerpted from AMERICAN SCARE by Robert W. Fieseler, published on June 17, 2025 by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright ©2025 Robert Fieseler.