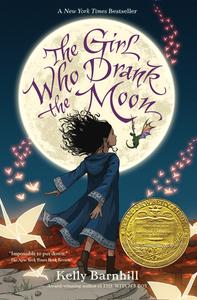

Yesterday, at the American Library Association's Youth Media Awards in Atlanta, Ga., Kelly Barnhill won the Newbery Medal for her fourth fantasy novel, The Girl Who Drank the Moon (Algonquin Books for Young Readers). Her novels The Witch's Boy and The Mostly True Story of Jack received four starred reviews, and Iron Hearted Violet received a Parents' Choice Gold Award and was an André Norton Award finalist. She lives in Minnesota with her husband and three children. Barnhill talked with Shelf Awareness on the phone shortly after winning the Newbery for her delightful, thought-provoking fantasy about "a 500-year-old witch and a poetry-quoting swamp monster and a perfectly tiny dragon with delusions of grandeur who all have to raise a magical baby."

_Bruce_Silcox_012317.jpg)

|

|

| photo: Bruce Silcox | |

Congratulations, Kelly! Tell us about "the call." Everyone always wants to hear the stories of where the authors were when they received their early-morning call from the Newbery Medal committee.

Nobody tells you how weird it is to get woken up at 5:15 in the morning by a roomful of librarians, you know. I was literally dead asleep. Dead, dead, dead asleep. Because it did not occur to me that this was even a remote possibility. And, in fact, there were a couple of people, even this weekend, who said it could happen, and each time I responded to them with total derision and disdain.

I have my phone in my room and my kids had changed the ringtone to the opening theme song for Wonder Woman, the old '70s TV show. So, first of all, that blasts me awake and I was totally disoriented, and I answer the phone and it's literally a roomful of librarians... cheerful librarians! And they're so excited. It's moving to me, because I know how much work goes into that, how seriously they take children's literature. That made me cry a little bit. Not so much what they were saying to me, but their work.

It's a strange thing for me because this book is incredibly dear to my heart-- and I was proud of it--but I didn't think that anyone would like it when I published it, honestly. In fact I had pre-written all my terrible reviews in my head... to save people the trouble... because I'm a Minnesotan, and I like to be helpful. But the first reviews came back so positive, I was shocked by it.

Tell us about the 13-year-old girl in The Girl Who Drank the Moon.

Luna! Luna is a child who does not know her own story. She only knows parts of her own story. She was a fun character to write because she's being raised by a very strange, but very loving family. When people ask me what my book's about, it's always very fun to say I'm writing a book about a 500-year-old witch and a poetry-quoting swamp monster and a perfectly tiny dragon with delusions of grandeur who all have to raise a magical baby. But the story's really about Luna.

She's coming to grips with the fact that her body is changing and her life is changing and her mind is changing in ways that happen to all of us, because all of us do grow. We realize that the world is not what we thought it was. And that can be confusing and enraging too, right? Sometimes kids, in the process of their growing up, experience rage because "Why is it like this and why is it that the things that I once could rely on, I suddenly can't?" Suddenly their forward motion is on their own two feet.

I liked writing about Luna because Luna is a prickly girl. I like writing about prickly girls and knowing about prickly girls because I was a prickly girl, and prickly girls don't get the credit that they need. She's prickly for a reason. She has a lot going on, a lot that she's trying to understand. But in the midst of all that is she feels so deeply. Her love for her grandmother and for her swamp monster and for her dragon are incredibly genuine, even though she understands that she's not being told the whole truth and that her family's need to protect her is genuine.

You said writing this book was dear to your heart. Why?

You said writing this book was dear to your heart. Why?

First of all, I really needed to spend some time thinking about the strange shape that a family can take and the strange shapes that love can take and how even though we can love one another with all of the fervor and the tenderness that goes with that, that we still make mistakes. We still get things wrong. And we still sometimes try to protect one another from sadness or harm even though it can be the actual protection that causes the sadness and harm. That was important for me to explore.

Where did the book come from?

I really started this book because of Glerk, the swamp monster. He was the very first thing that showed up. He was holding a daisy and he was saying a poem, actually the very last poem in the book. So I wrote down the poem and it appears, verbatim, just how I wrote it way back then. I don't know why I was thinking about a swamp monster. I'm not a visual thinker at all. It's extremely rare for me to get pictures in my head. So whenever I get an image in my head that pops up unbidden, first of all, I find it exhausting, and second of all, I pay attention to it because it's usually important, even if I don't know why.

So what does Glerk look like?

In my mind's eye, that one time I got a clear picture of Glerk, he was the color of algae, bright-green algae in a bog. And his eyes were very wide-spaced apart and very large. One thing that I don't think got into the text but is true is that his eyes move independently of one another. He's got very broad, damp jaws. So if you can imagine the face of a Chinese dragon but just generally more damp? I live in Minnesota, there are bogs everywhere; I have a great affinity for damp landscapes that are filled with life. He's of that substance, which might be gross to some people, but it's marvelous to me.

How did you manage such a complex plot structure? Storyboards? Index cards?

It's all instinct. My revision technique basically involves, "Select All/Delete." I do that a lot. It's not something I highly recommend, but it is mine, so I will claim it. It's returning again and again and again. Different threads will pull and tease out and wind around. Everything that makes sense is purely accidental. (Laughs.)

What are you working on now?

I'm working on a new book called The Sugar House, a retelling of the Hansel and Gretel story set in Minneapolis, in which the diabetic kid saves the day but nobody will believe him because he blew up the school. Not really, but that's how it plays in the media. It's about a kid who makes bad choices for sure, but he's a really good kid.

Speaking of how things play in the media, The Girl Who Drank the Moon addresses the recent discussions of "fake news" in a way, since the entire City of Sorrows is perpetuating a tragic tradition based on a lie they think is true.

I have a lot of friends who are journalists, and I remember in the fall after Hurricane Katrina we were having all these conversations about how the way we frame narrative can distort the facts. Are the people coming out of the broken store looters or scavengers? Well, it depends on my internal biases, right? So that was so interesting to me, and I wanted to be able to explore that in fiction. I didn't realize that this whole notion of fake news and false narratives would be so very relevant right now. I'm glad I can at least provide one avenue for people to discuss it.

It's been very gratifying to me to be able to talk to kids about big ideas like this. Fourth and fifth graders are incredibly global in how they think. And they are literally writing the universe with every step they take through the world. It's exciting. Books are so important for kids this age because they're tools and they're maps and they're lamps and they're swords and they're everything that they need to be able to navigate, and also rewrite, and also rebuild. It's a huge honor to be part of that process of mind-making and world-making. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness