I've written about retail mourning before, as far back as my bookselling days at the turn of the century. I may have even conjured the term. Most authors outlive their books and watch them vanish from print (even if digital ghosts remain to haunt), but for the lucky ones, their books outlive them.

When that happens, retail mourning occurs in bookshops. Buyers order multiple copies of the author's backlist, including early titles from small and university presses that the shop might not have carried for years. Booksellers create display memorials with whatever stock is on hand, adding appropriate signage. Everybody sells out, literally and figuratively, but in a nice way.

Upon learning that an author has passed, some readers head to bookstores because they feel compelled to seek out "books by that writer who just died. I never heard of him, but he sounds interesting." Or because they can't find the copies they bought years ago (which they know are hiding somewhere in the house or were loaned to friends/relatives and never returned).

|

|

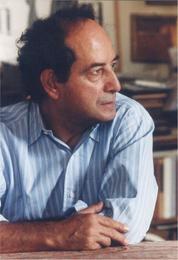

| Roberto Calasso | |

Something along these lines happened to me last month when I learned of Italian publisher, translator and writer Roberto Calasso's death. The New York Times described him as "a rare figure in the literary world--an erudite writer and polymath and a savvy publisher who was able to reach a substantial readership for books he released through Adelphi Edizioni, the prestigious Italian publishing house where he worked for some 60 years."

Jonathan Galassi, president of Farrar Straus & Giroux, which published eight of Calasso's titles, said: "He was always finding writers who hadn't had their due and he was always good at publicizing them when he published a book. He was kind of a literary magician."

As sometimes (well, too often) happens, I found myself questioning why I hadn't read more of Calasso's work, and vowed to correct the lapse. The book that called out to me wasn't among his more acclaimed titles, but one I somehow hadn't been aware of at all--The Art of the Publisher, translated by Richard Dixon (FSG, 2015). So I read it, and immediately became evangelical about it. Windows into the book trade are seldom left open. We should peek inside whenever we have the chance.

As sometimes (well, too often) happens, I found myself questioning why I hadn't read more of Calasso's work, and vowed to correct the lapse. The book that called out to me wasn't among his more acclaimed titles, but one I somehow hadn't been aware of at all--The Art of the Publisher, translated by Richard Dixon (FSG, 2015). So I read it, and immediately became evangelical about it. Windows into the book trade are seldom left open. We should peek inside whenever we have the chance.

I don't need to review The Art of the Publisher. I'm not a reviewer. And I don't have to handsell it. I'm not a bookseller anymore. What I'd like to do, though, is share a few of Calasso's own words. As I read him, I found myself composing a sort of commonplace book of his sharp observations. Here's the gift of a sampling:

*We can therefore conclude that, apart from being one branch of business, publishing has always involved prestige, if only because it is a kind of business that is also an art. An art in every sense, and certainly a dangerous art since, in order to practice it, money is an essential element. From this point of view it can be argued that very little has changed since Gutenberg's time.

*Try to imagine a publishing house as a single text formed not just by the totality of books that have been published there, but also by all its other constituent elements, such as the front covers, cover flaps, publicity, the quantity of copies printed and sold, or the different editions in which the same text has been presented.

*So the publisher who chooses a book cover--whether he realizes it or not--is the last, the most humble and obscure descendant in the line of those who practice the art of ekphrasis, but this time applied in reverse, attempting to find the equivalent or the analogon of a text in a single image.

*The point is that universal digitization implies a certain hostility toward a way of knowledge--and only as a consequence toward the object that embodies it: the book. It is not therefore a matter of being concerned about the survival of the book itself. The book has already encountered difficult times and has always endured. No one, after all, wishes it much harm.

*It wasn't a matter, he said, of deploring a general indifference of readers, but of finding out first of all what they are indifferent to.

*We watch a reader in a bookshop: he picks up a book, leafs through it--and for a short instant he is entirely cut off from the world. He is listening to someone speaking, whom others cannot hear. He gathers random fragments of phrases. He shuts the book, looks at the cover. Then he often takes a brief glance at the cover flap, hoping for some assistance. At that moment, without realizing it, he is opening an envelope: those few lines, external to the text of the book, are like a letter written to a stranger.

In his book The Celestial Hunter, Calasso observes: "A book is written when there is something specific that has to be discovered. The writer doesn't know what it is, nor where it is, but knows it has to be found. The hunt then begins. The writing begins." A book can be read for the same reason. The Art of the Publisher is my (belated) discovery.