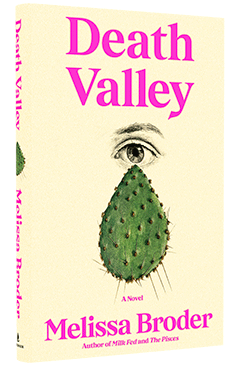

Death Valley

by Melissa Broder

In Death Valley, Melissa Broder (Milk Fed; The Pisces) brilliantly dissects the intersections of grief, loss, and depression (heavy topics, all approached with an unexpected sense of humor) through her protagonist, an author ostensibly seeking inspiration for her next novel. The unnamed woman flees to a desert motel in hopes of finding not just a story, but an escape from her own life--only to learn that escape in the desert can prove more dangerous than she ever might have imagined.

Pulling into a Best Western well outside of Los Angeles, the woman reflects on the weight of the emptiness she carries around inside. In desperation, she reminds herself that her "doominess isn't baseless," but borne of a life in L.A. that feels unmanageable (as though that reminder might somehow make it feel more manageable). "There's something to be said for manufacturing a crisis (a crisis can be simpler than just living)," she reflects, though she has no need to manufacture crises when life has offered her plenty of them. Her father has been in and out of intensive-care units and on the brink of death for five months, following a tragic accident, alternating between prolonged bouts of unconsciousness and surprising revivals. Her husband has spent nine long years with a debilitating and seemingly undiagnosable illness that leaves him bedridden for months on end. It seems her whole life has been about taking on other people's feelings as hers to manage, as the eldest daughter of a depressed father and a mother unwilling to acknowledge--let alone speak about--emotions of any sort: "I came to escape a feeling--an attempt that's already going poorly, because unfortunately I've brought myself with me, and I see, as the last pink light creeps out to infinity, that I am still the kind of person who makes another person's coma all about me."

The Best Western receptionist encourages the woman to order the blueberry muffin for breakfast (and definitely not the breakfast sandwich), and then to visit a local hiking trail. There, she finds huge cactuses--one so enormous she believes she can enter its cavity through a splice in its side, and so much larger-than-life that, once inside, she sees within it her father as a guitar-playing boy in his prime. She is entirely sober (refusing even cough syrup after struggling with addiction and recovery), and the image is clear enough to present as reality. "Does having visions inside a cactus count as a relapse?" she ponders to the sand and rocks. With the discovery of the revelatory cactus--which the staff of the Best Western insist cannot and does not exist--Death Valley slips out of reality and into something akin to a fever dream, with the boundaries between what is real and what is imagined (and what, perhaps, is a mirage) ever blurring along the way.

Self-described as a sober woman of many years, struggling with depression, the heroine is overly prone to "trying to solve a problem, the problem of me and my mood, rather than just experiencing it. But how do you just experience things?" This question, so pivotal to her desert flight to begin with, becomes moot when she takes a wrong turn on the trail, and finds herself thoroughly and completely lost in the wilderness: alone, unprepared, with limited water and just a bag of motel to-go breakfast for sustenance. Her only conversation partners are the rocks she's found and named (and granted personalities: The Egg, Grey, Door, etc.). And thus, her experience is reduced to just that: an experience, devoid of emotion, empty of the things that used to scare her. Instead of obsessing about "doom, mood, magic daughter, anticipatory grief, husband illness, bed-vortex, Montezuma Cypress, not good enough, the sky," she is--and must be--focused on survival: sips of water, shade in the daytime, warmth at nightfall, the limited battery in her phone, and continued lack of signal to call for help.

Within this desperate (if unanticipated) desire to simply survive, she finds a kind of presence she's not known before, one brought to life in Broder's elegant descriptions of the unexpectedly beautiful details of desert wilderness that appears barren from afar: "The crystallized beavertails. The rising sandstone wall and the steepening drop. Pistachio moss, chartreuse moss. Yellow flowers. Eroded ghost emoji log." (The latter representative of her enduring sense of humor, even in the darkest of moments.)

Ultimately, Death Valley is a story centered on survival: what it means to survive in a landscape not primed for human thriving, be it the literal desert or the more emotional world of anticipatory grief and loss, and what it means to survive a deep, unfathomable sense of loneliness while craving aloneness with a kind of wild desperation. In Broder's skilled hands, a story that could read as hopeless and desperate proves heartfelt and tender, moving seamlessly between the surreal and the all-too-real and back again. At times disorienting, at times familiar, and beautiful throughout, Death Valley is a smart, darkly comedic novel that reimagines the experience of grief in inspired and unexpected ways. --Kerry McHugh