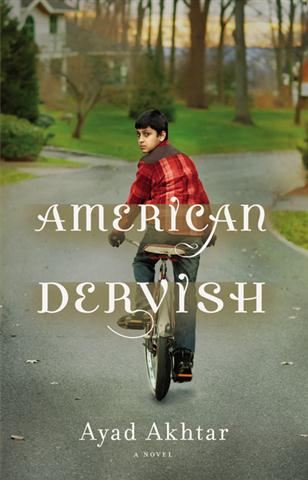

American Dervish by Ayad Akhtar (Little, Brown, $24.99 hardcover, 9780316183314, January 9, 2012)

American Dervish opens with an epigram from the Hadith Qudsi (sacred sayings of Muhammad): "And Allah said: I am with the ones whose hearts are torn." A fitting quote for this moving, insightful story about religion and family, immigration and assimilation, wherein hearts are numbed, warmed and broken. Faith and love are found, lost and re-formed as the narrator, Hayat Shah, travels a jagged road through the early years of adolescence with all its confusions and dramatic certainties.

American Dervish opens with an epigram from the Hadith Qudsi (sacred sayings of Muhammad): "And Allah said: I am with the ones whose hearts are torn." A fitting quote for this moving, insightful story about religion and family, immigration and assimilation, wherein hearts are numbed, warmed and broken. Faith and love are found, lost and re-formed as the narrator, Hayat Shah, travels a jagged road through the early years of adolescence with all its confusions and dramatic certainties.

In the prologue, Hayat remembers a watershed moment: at a college basketball game with two friends, he orders two bratwurst and a beef dog from a vendor. What they get are three brats. At that instant, Hayat decides he has no reason not to eat one.

"I lifted the sausage to my mouth, closed my eyes, and took a bite. My heart raced as I chewed, my mouth filling with a sweet and smoky, lightly pungent taste that seemed utterly remarkable--perhaps all the more so for having been so long forbidden. I felt at once brave and ridiculous. And as I swallowed, an eerie stillness came over me.

"I looked up at the ceiling.

"It was still there. Not an inch closer to falling in.

"After the game, I walked along the campus quad alone, the walkway's lamps glowing in the mist, white blossoms on a balmy November night. The wet air swirled and blew. I felt alive as I moved. Free along my limbs. Even giddy.

"Back at the dorm, I stood before the bathroom mirror. My shoulders looked different. Not huddled, but open. Unburdened. My eyes drew my gaze, and there I saw what I was feeling: something quiet, strong, still.

"I felt like I was complete."

The evening after the game, Hayat's mother calls to tell him that Mina had died--his mother's best friend and the person who'd had the greatest influence on his life. He is deeply grieved, and feels a haunting guilt as well.

Hayat's path to grief, guilt and ultimate grace starts in his boyhood home in a Milwaukee suburb. How a bratwurst sums up the journey Hayat has taken from that Pakistani, nominally Muslim home, the sifting through life lessons to find what really matters, the lesson learned about true faith as opposed to formulaic faith--all are limned beautifully and powerfully by Ayad Akhtar as he tells Hayat's, and Mina's, story.

Long before Hayat knew Mina he knew about her: gifted and gorgeous, her life was thwarted back in Pakistan, "her robust will checked by a culture that made no place for a woman." She was married to a weak-willed, wealthy man whose mother made her life a living hell. The day her son, Imran, was born, her husband divorced her, with the proviso that he take custody of the boy when he turned seven.

Hayat's parents are Naveed Shah, a neurologist, and Muneer, who gave up her psychology studies to come to America with him. Their marriage is difficult--Naveed's scorn for most of the Pakistani Muslim community has exacerbated Muneer's isolation, as has his personal life: they are awakened one night by flickering orange lights and fire trucks—Naveed's Mercedes had been set afire by "one of [his] white bitches." But after this latest episode of humiliation, Muneer has the upper hand and decides on the consequence: Mina and her son will come to live with them. When she arrives in Wisconsin, Muneer is ecstatic, and Hayat is entranced.

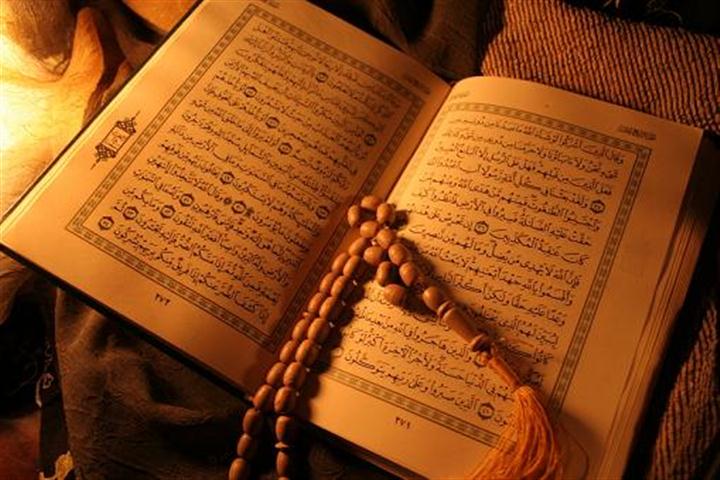

Hayat is drawn not only to her beauty, but to her religion. Mina tells him stories about Muhammad's life, which he has never heard. On the eve of his 11th birthday, Mina gives Hayat his own Quran. For Mina, faith isn't about the outer forms--headscarves, fasting--but about intent. She's an advocate of personal interpretation, and is intent on getting Hayat to think; Hayat is intent on gazing at Mina. And so, entranced with both Mina and the Quran, awestruck by the thought of infinity, marveling at God's majesty, he decides to become a hafiz, one who has memorized the Quran. But his father is not so sanguine about his son's growing religious intensity.

Hayat is drawn not only to her beauty, but to her religion. Mina tells him stories about Muhammad's life, which he has never heard. On the eve of his 11th birthday, Mina gives Hayat his own Quran. For Mina, faith isn't about the outer forms--headscarves, fasting--but about intent. She's an advocate of personal interpretation, and is intent on getting Hayat to think; Hayat is intent on gazing at Mina. And so, entranced with both Mina and the Quran, awestruck by the thought of infinity, marveling at God's majesty, he decides to become a hafiz, one who has memorized the Quran. But his father is not so sanguine about his son's growing religious intensity.

Life in the Shah house settles into a peaceful, even happy state, although coming from the world they did, happiness was not an expectation, unhappiness was. The message has always been: "Do not expect anything other than loss, pain, sorrow." So when Naveed invites his friend Nathan Wolfson, who is Jewish, to the Shahs' for a barbeque, and Nathan and Mina are smitten with each other, there are problems. Imran is jealous, and Mina worries about what her family back home will say, although Muneer points out that Nathan's being Jewish is a good thing because they understand how to treat a woman; Muslim men are terrified of women, all of them. And Hayat is jealous of Nathan--of anything, really, that would occupy Mina's time; his emotion is mixed with a hateful stew of anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism that he now hears from Muslim men around him. Add a fiery tirade against Jews at his first visit to the mosque, and Hayat does something wrong and irretrievable.

Life in the Shah house settles into a peaceful, even happy state, although coming from the world they did, happiness was not an expectation, unhappiness was. The message has always been: "Do not expect anything other than loss, pain, sorrow." So when Naveed invites his friend Nathan Wolfson, who is Jewish, to the Shahs' for a barbeque, and Nathan and Mina are smitten with each other, there are problems. Imran is jealous, and Mina worries about what her family back home will say, although Muneer points out that Nathan's being Jewish is a good thing because they understand how to treat a woman; Muslim men are terrified of women, all of them. And Hayat is jealous of Nathan--of anything, really, that would occupy Mina's time; his emotion is mixed with a hateful stew of anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism that he now hears from Muslim men around him. Add a fiery tirade against Jews at his first visit to the mosque, and Hayat does something wrong and irretrievable.

The conflict between and within religions, and the more unfamiliar places of agreement--Abraham and Ibrahim, dust to dust, God's compassion and mercy, hellfire and God's vengeance—are timeless and universal. Ayad Akhbar's explorations into the tension between the universal truths of religion and literal readings of its documents plays out effectively in American Dervish, his debut novel. Already a master of scene and dialogue, and evocative prose, he's created a compelling and visceral story. When Mina teaches Hayat to listen to the still small voice within that can only be heard by finding the silence at the end of a breath, Hayat tries, and discovers what will continue to inspire him to find the still, small voice hidden between and beneath each breath, and, with it, wisdom and insight. --Marilyn Dahl

American Dervish opens with an epigram from the Hadith Qudsi (sacred sayings of Muhammad): "And Allah said: I am with the ones whose hearts are torn." A fitting quote for this moving, insightful story about religion and family, immigration and assimilation, wherein hearts are numbed, warmed and broken. Faith and love are found, lost and re-formed as the narrator, Hayat Shah, travels a jagged road through the early years of adolescence with all its confusions and dramatic certainties.

American Dervish opens with an epigram from the Hadith Qudsi (sacred sayings of Muhammad): "And Allah said: I am with the ones whose hearts are torn." A fitting quote for this moving, insightful story about religion and family, immigration and assimilation, wherein hearts are numbed, warmed and broken. Faith and love are found, lost and re-formed as the narrator, Hayat Shah, travels a jagged road through the early years of adolescence with all its confusions and dramatic certainties. Hayat is drawn not only to her beauty, but to her religion. Mina tells him stories about Muhammad's life, which he has never heard. On the eve of his 11th birthday, Mina gives Hayat his own Quran. For Mina, faith isn't about the outer forms--headscarves, fasting--but about intent. She's an advocate of personal interpretation, and is intent on getting Hayat to think; Hayat is intent on gazing at Mina. And so, entranced with both Mina and the Quran, awestruck by the thought of infinity, marveling at God's majesty, he decides to become a hafiz, one who has memorized the Quran. But his father is not so sanguine about his son's growing religious intensity.

Hayat is drawn not only to her beauty, but to her religion. Mina tells him stories about Muhammad's life, which he has never heard. On the eve of his 11th birthday, Mina gives Hayat his own Quran. For Mina, faith isn't about the outer forms--headscarves, fasting--but about intent. She's an advocate of personal interpretation, and is intent on getting Hayat to think; Hayat is intent on gazing at Mina. And so, entranced with both Mina and the Quran, awestruck by the thought of infinity, marveling at God's majesty, he decides to become a hafiz, one who has memorized the Quran. But his father is not so sanguine about his son's growing religious intensity. Life in the Shah house settles into a peaceful, even happy state, although coming from the world they did, happiness was not an expectation, unhappiness was. The message has always been: "Do not expect anything other than loss, pain, sorrow." So when Naveed invites his friend Nathan Wolfson, who is Jewish, to the Shahs' for a barbeque, and Nathan and Mina are smitten with each other, there are problems. Imran is jealous, and Mina worries about what her family back home will say, although Muneer points out that Nathan's being Jewish is a good thing because they understand how to treat a woman; Muslim men are terrified of women, all of them. And Hayat is jealous of Nathan--of anything, really, that would occupy Mina's time; his emotion is mixed with a hateful stew of anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism that he now hears from Muslim men around him. Add a fiery tirade against Jews at his first visit to the mosque, and Hayat does something wrong and irretrievable.

Life in the Shah house settles into a peaceful, even happy state, although coming from the world they did, happiness was not an expectation, unhappiness was. The message has always been: "Do not expect anything other than loss, pain, sorrow." So when Naveed invites his friend Nathan Wolfson, who is Jewish, to the Shahs' for a barbeque, and Nathan and Mina are smitten with each other, there are problems. Imran is jealous, and Mina worries about what her family back home will say, although Muneer points out that Nathan's being Jewish is a good thing because they understand how to treat a woman; Muslim men are terrified of women, all of them. And Hayat is jealous of Nathan--of anything, really, that would occupy Mina's time; his emotion is mixed with a hateful stew of anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism that he now hears from Muslim men around him. Add a fiery tirade against Jews at his first visit to the mosque, and Hayat does something wrong and irretrievable.

Your narrator, Hayat Shah, is a young man looking back on a period during his childhood when he learned about his Muslim spiritual heritage. What inspired you to combine study of the Quran with Hayat's family story of immigration, assimilation and their challenges in aligning Pakistani and American culture?

Your narrator, Hayat Shah, is a young man looking back on a period during his childhood when he learned about his Muslim spiritual heritage. What inspired you to combine study of the Quran with Hayat's family story of immigration, assimilation and their challenges in aligning Pakistani and American culture? If anything, these mornings were even sweeter: the trees stippled with turning leaves and bathed in a glorious light that seemed like much more than just the sun's illumination; the white clouds sculpted against blue skies, stacked like majestic monuments to the Almighty's unfathomable glory. And it wasn't only beauty that moved me in these heightened states. Even the grease-encrusted axle of the yellow school bus slowing to its morning stop at the end of my driveway could captivate me, its twisting joint—and the large, squeaking wheel that turned around it—seeming to point the inscrutable way to some rich, strange, and holy power.

If anything, these mornings were even sweeter: the trees stippled with turning leaves and bathed in a glorious light that seemed like much more than just the sun's illumination; the white clouds sculpted against blue skies, stacked like majestic monuments to the Almighty's unfathomable glory. And it wasn't only beauty that moved me in these heightened states. Even the grease-encrusted axle of the yellow school bus slowing to its morning stop at the end of my driveway could captivate me, its twisting joint—and the large, squeaking wheel that turned around it—seeming to point the inscrutable way to some rich, strange, and holy power.