Hospitality has turned out to be more precious and more fragile than we appreciated.

--William Davies, London Review of Books (June 17)

Covid-19 pandemic media coverage tends to link the word hospitality to sector. In his recent LRB column, Davies writes: "The slow reopening of the British hospitality sector over the past few weeks signals a re-emergence from the great closures of the last year and a half--hopefully, this time, a permanent re-emergence, though who knows?"

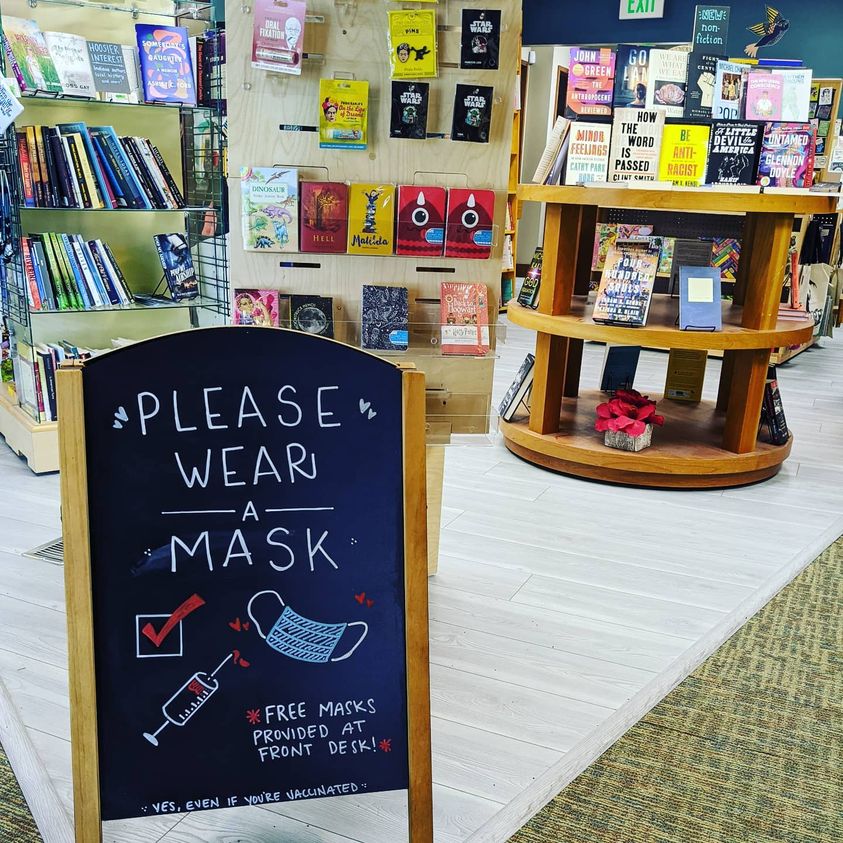

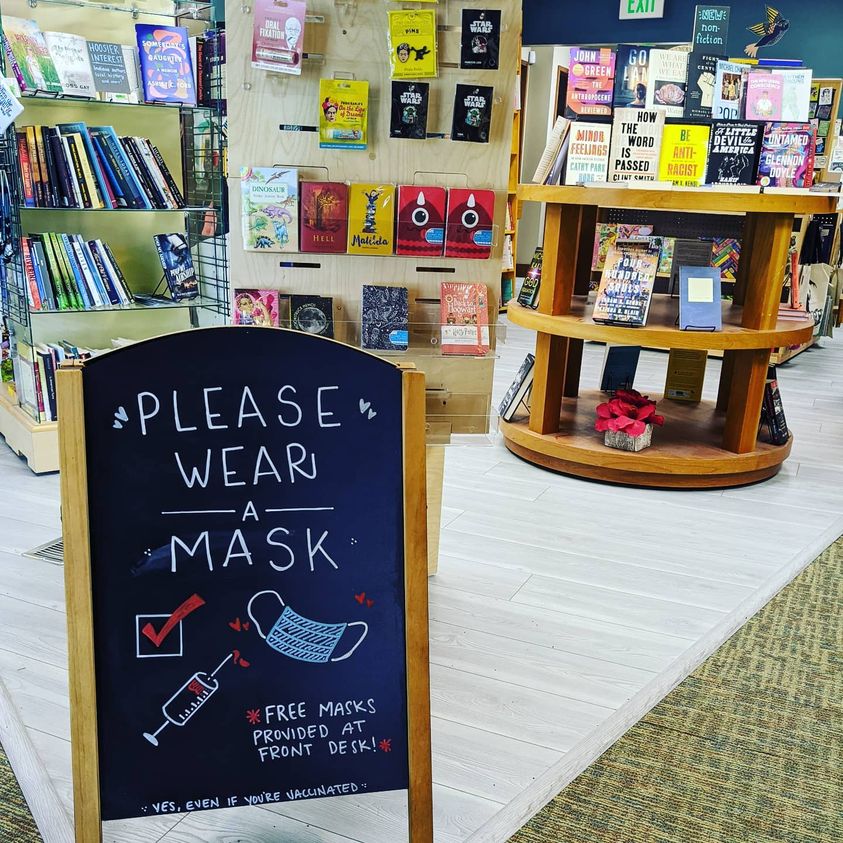

|

| At Mysterious Galaxy, San Diego, Calif. |

But hospitality is an appropriate and important word for indie bookstores as well, though the tendency is often to lean on service. Legendary restaurateur Danny Meyer (who announced an upcoming Covid policy change for his establishments yesterday) once summed up the compatible difference: "Service can be measured based on how well a product was technically delivered. Hospitality can be measured based upon how the recipient of that service felt. Hospitality exists when something happens for you, not to you. It exists when you believe the other person is on your side. Service is truly a monologue. Hospitality has to be a dialogue."

When I was a bookseller, we had endless discussions in meetings about how to get people who hadn't been to the bookshop before to just open the damn front door and come inside--how to project hospitality in order to be of service.

Hospitality is not a simple word. Davies explains that it is "from the Latin hospes--host, guest, stranger or foreigner--which in turn derives from hostis, meaning stranger or enemy.... Hospitality is the terrain of both safety and danger. A handshake (another casualty of Covid-19) symbolizes the absence of a weapon, but only because a weapon is a real possibility; members of the same household do not shake hands. By contrast, the recently deregulated hug isn't strictly a gesture of hospitality at all. Hospitality is never without risk: it involves taking the outsider--the foreigner, the potential enemy--into one's home as a guest. Conversely, hospitality is not truly hospitality if the host doesn't retain some authority to exclude: to be a guest is to be invited in, to cross a threshold of some kind.... The host must choose whether to treat the stranger as a guest or as an enemy. Remove the discretion of the host, and what is left of hospitality?"

I used to know a corporate consultant for the hotel, cruise ship and restaurant industry--the hospitality sector. For decades, he routinely flew all over the planet to lead seminars for frontline and middle management staff. A great believer in the importance of "the last three feet," he focused on that critical moment when a member of the company's staff personally, physically, psychologically and emotionally transfers "product"--a meal, a room key, an entertainment recommendation--across the unfathomable gap between the corporation and an individual consumer/guest.

A patron of our bookshop, he would occasionally lead sessions for the staff, sharing wisdom about the "last three feet" between a bookseller handselling a title and their reader/customer. This was my preferred retail mantra for a long time. Then Covid-19 stretched the hospitality gap to six feet; added face masks, plexiglass shields, hand sanitizer stations; and, for a time, shuttered bookshop front doors completely.

|

| At Second Flight Books, Lafayette, Ind. |

"Hospitality loses its ambivalence, and becomes instead a procedural matter of openings and closures," Davies writes of pandemic mentality, "in which the discretion no longer lies with the parties concerned. In such a world there are no real hosts and no real strangers, just identities to be checked: a hostile environment."

Forget about wondering how to get more people to open the front door. Suddenly, the trick was to find hospitable ways to keep the Covid zombies out, while simultaneously reinventing online hospitality through mail-order, curbside or window pickups, home deliveries (asking customers to open their front doors) and more. And even when cautious reopening became a possibility, the number of customers permitted inside proved to be a challenging metric.

Confusion and controversy still reign throughout the land. As just one example, this week KNWA reported that at Dickson Street Bookshop, Fayetteville, Ark., "there had been several situations where it's had to close because of an employee testing positive for Covid-19. This, in addition to the store being a small setting with tight walking spaces, is why store manager Suedee Hall-Elkins said what makes them feel comfortable is requiring masks inside the shop."

Confusion and controversy still reign throughout the land. As just one example, this week KNWA reported that at Dickson Street Bookshop, Fayetteville, Ark., "there had been several situations where it's had to close because of an employee testing positive for Covid-19. This, in addition to the store being a small setting with tight walking spaces, is why store manager Suedee Hall-Elkins said what makes them feel comfortable is requiring masks inside the shop."

But enforcing the policy is a daily struggle, with booksellers "being verbally assaulted; it has caused an overall loss in business and for people to leave hateful public reviews online that have nothing to do with the product or customer service," KNWA noted.

"It's incredibly frustrating because if there were just a mask mandate, then it wouldn't be on us, and people wouldn't come in and attack us personally," said Hall-Elkins. "You know it would just be this is how it is right now because we are trying to do the right thing to protect everyone."

In his LRB essay, Davies observes: "What's most likely is that 'normality' will return, but with invisible costs and harms: a new wariness towards the stranger, a new attitude towards 'home,' a new set of hidden codes determining who gains entry and who does not. How we undo these innovations, and whether it's even possible to do so, remains to be seen."

Kindred Creatives Art and Literary Press, a Black-owned bookstore focused on sharing the work of BIPOC authors and creatives, has opened in the Music City Mall in Lewisville, Tex., Dallas News reported.

Kindred Creatives Art and Literary Press, a Black-owned bookstore focused on sharing the work of BIPOC authors and creatives, has opened in the Music City Mall in Lewisville, Tex., Dallas News reported.

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

Paradis Books & Bread

Paradis Books & Bread In the second quarter ended June 30, net sales at Amazon rose 27.2%, to $113.1 billion, and net income rose 50%, to $7.8 billion. The strong sales results were below analysts' expectations, however, and are, the Wall Street Journal wrote, "

In the second quarter ended June 30, net sales at Amazon rose 27.2%, to $113.1 billion, and net income rose 50%, to $7.8 billion. The strong sales results were below analysts' expectations, however, and are, the Wall Street Journal wrote, " Barnes & Noble is closing one store in suburban Cincinnati, Ohio, and opening another later this year,

Barnes & Noble is closing one store in suburban Cincinnati, Ohio, and opening another later this year,

Author

Author

"

" "If it's been a while since you've been taken by a good read,

"If it's been a while since you've been taken by a good read,

.jpg) Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: In her debut collection, Skinship: Stories, Yoon Choi tells eight tales of Korean Americans, skillfully highlighting both the particulars of their experience and also the extent to which they share challenges in common with other immigrants to the United States. Their locales range from small cities and suburbia to New York City, with occasional glimpses of Korea; Choi's stories are rooted in the quotidian experiences of family and work life, painting a realistic portrait of the difficulties her subjects face in acclimating to a new land and their progress in doing so.

In her debut collection, Skinship: Stories, Yoon Choi tells eight tales of Korean Americans, skillfully highlighting both the particulars of their experience and also the extent to which they share challenges in common with other immigrants to the United States. Their locales range from small cities and suburbia to New York City, with occasional glimpses of Korea; Choi's stories are rooted in the quotidian experiences of family and work life, painting a realistic portrait of the difficulties her subjects face in acclimating to a new land and their progress in doing so.

Confusion and controversy still reign throughout the land. As just one example, this week KNWA reported that at

Confusion and controversy still reign throughout the land. As just one example, this week KNWA reported that at