ABA Snow Days: Unions 101

On Tuesday afternoon, at the ABA Snow Days conference, lawyers Jon Hiatt and Mark R. Reiss convened to provide a detailed overview of the unionization process and what it means for both bookstore employees and bookstore owners. Hiatt, a union-side labor lawyer, offered perspectives from the employee side, while Reiss, who has represented clients in collective bargaining and labor arbitration, offered the employers' perspective.

On Tuesday afternoon, at the ABA Snow Days conference, lawyers Jon Hiatt and Mark R. Reiss convened to provide a detailed overview of the unionization process and what it means for both bookstore employees and bookstore owners. Hiatt, a union-side labor lawyer, offered perspectives from the employee side, while Reiss, who has represented clients in collective bargaining and labor arbitration, offered the employers' perspective.

Allison Hill, CEO of the American Booksellers Association, and Joy Dallanegra-Sanger, ABA's chief operating officer, introduced the session.

They began with a discussion of the reasons why employees typically unionize. Reiss noted that there are sometimes very clear, specific reasons why workers unionize--such as dissatisfaction with wages or benefits, poor working conditions, lack of job security, or the inconsistent application of rules and policies by management--as well as more general reasons like a perceived lack of dignity or respect in the workplace. Historically, the vast majority of employees have unionized because of the clear or "obvious" reasons, he continued, but over the past few years many more efforts "have come from the second group." Those workers are still concerned about wages, benefits and the handling of workers' grievances, but they are equally concerned about dignity, appreciation and respect.

On the pros and cons of unionization, Reiss said both sides can benefit from the "standardization of things" that organizing provides. Once labor and ownership agree to a union contract, everything from wage structures and benefits to the handling of grievances will be spelled out in the contract, which provides a certain level of "consistency and stability." Union contracts run for multiple years, which gives employers the ability to budget for labor costs for years ahead. Employees have the same luxury, as they will know their rate of pay for the next few years. As for cons, he said, that same standardization can lead to some inflexibility for individual employees, depending on the terms of the union contract.

Hiatt acknowledged that standardization could make it difficult to address individual concerns, but the "key value" of collective bargaining is that it is "tailored to particular workplaces." There's no inherent reason that a union contract can't standardize wages while also allowing for merit increases, or standardize hours while providing for varying circumstances. And when issues arise that neither party has foreseen, they can negotiate an addendum to the union contract. Both labor and management can benefit from new, streamlined ways of handling complaints, and contracts frequently have a management rights clause, as well as clauses stipulating there can be no strikes or lockouts.

Discussing the nuts and bolts of the unionization process, Hiatt remarked that it is "extremely rare" for the process to start with an outside force encouraging workers to unionize, given how low the density of labor unions actually is. It "almost always" starts internally, and sometimes workers seek help from an outside union and sometimes workers stay independent. From there the process can go one of two ways, either through voluntary recognition, which legally requires a neutral third party confirming that a majority of employees want to unionize, or through a National Labor Relations Board election, which is typically a "much more drawn-out and contentious process."

There are "strict ground rules" for many parts of the process, including who can or cannot be part of a union. Bargaining units are made up of employees in the workplace minus supervisors, managers, temporary employees and similar categories. Hiatt observed that sometimes the distinction between a "lead person" and supervisor is clear, and at other times it is "borderline." In the case of voluntary recognition, the parties can "agree among themselves" who is in and who is out. In the case of an NLRB election, the NLRB itself will decide, though both parties can make arguments and there is an eight-part test to legally determine if someone should be considered management.

During an election an employer can choose to remain neutral or choose to campaign against the union. Reiss explained that the list of things employers can't do during this process is commonly abbreviated as TIPS--Threats, Interrogation, Promises and Surveillance. Some examples of those actions include threatening to fire employees or to close the store if they unionize; questioning individual employees about their own or others' voting intentions; promising things like extra vacation days or pay raises if employees vote against the union; and attempting to spy on private conversations about the union. They can, however, share their own opinions about unionization, as well as facts about unions.

When it comes to union elections, Reiss emphasized that the union wins if it receives a majority of the votes not of the total bargaining unit but of those who showed up to vote. As an example, 100 people might be in a bargaining unit, but if only 10 show up to vote, six votes is enough to win. Should the union win, negotiations begin, and the first contract generally "takes a while" to complete. If the union doesn't get a majority of votes, then there is a one-year bar for that union or any other union to petition the employees of that store or company.

In the panel's anonymous q&a portion, an attendee asked how union contracts work when it comes to things like individual needs for neurodivergent employees. On issues where there is public legislation across the board, whether that be minimum wage, overtime, Title VII or Americans with Disabilities Act protections, those don't go away, Hiatt answered. Unions and employers typically don't include extensive language in cases where there are already legal protections, but they may add things beyond that in certain circumstances. And whether unions and employers include more in the collective bargaining agreement or not, unionization typically provides a "more efficient and inexpensive way" to resolve such disputes. Reiss said it is also very common for union contracts to provide for things like military leave or bereavement leave, though they may be applicable only to a single employee or even no employees at any given time.

To a question about the value of bringing in an outside mediator to help with negotiations, Reiss noted that it can be valuable to have a "fresh voice" come in if parties are at an impasse, but it is a non-binding process. Hiatt agreed that bringing in a third party can have value, though that party may not be familiar with current circumstances and it can still present its own difficulties.

Asked about the advantages and disadvantages of starting a new union or joining an established union in a different industry, Hiatt reiterated that there are "way more workers trying to organize than unions available to help them." While there are no national bookstore unions that he knows of, there are retail workers unions and service employee unions, and they are not bound to any one sector or "jurisdiction."

Forming a new union is not necessarily better or worse than joining an established union, he said, but generally employees new to organizing are inclined to join an established union because of the expertise, resources and experience they can provide. Reiss advised that when workers are considering an established union, they should make sure they are comfortable with that union representing them going forward. --Alex Mutter

Canadian bookseller

Canadian bookseller

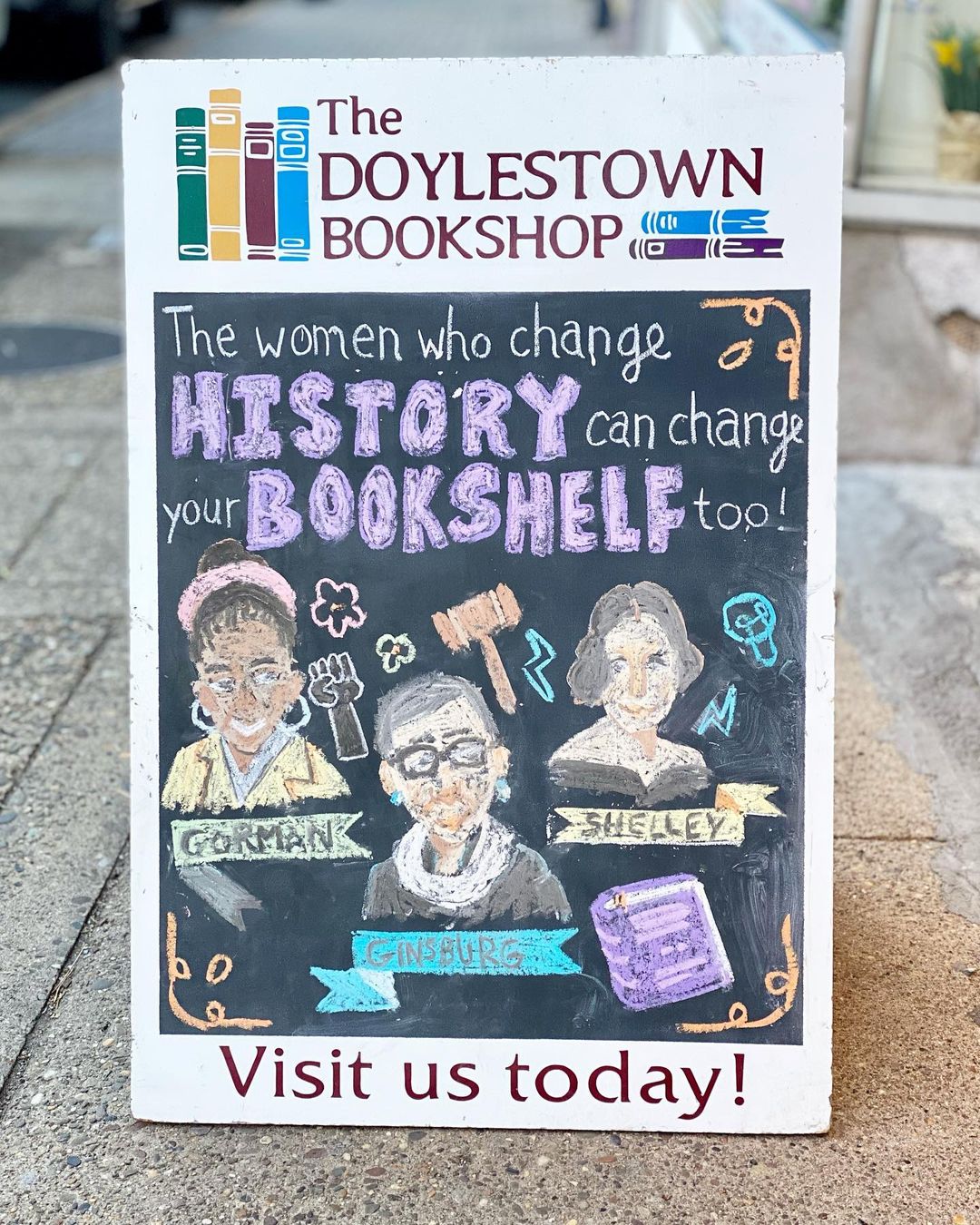

Celebrating Women's History Month, the

Celebrating Women's History Month, the  A wholeheartedly fun, over-the-top middle-grade dystopian (maybe?) novel celebrates the kind of childhood where kids can have a blast figuring out whether or not the world is coming to an end. And where the best junk food is.

A wholeheartedly fun, over-the-top middle-grade dystopian (maybe?) novel celebrates the kind of childhood where kids can have a blast figuring out whether or not the world is coming to an end. And where the best junk food is.