Changing the clocks back an hour from Daylight Saving Time last weekend felt like using a sundial, and made me think we need more times: Present Saving Time, Past Saving Time, Future Saving Time. And if we're going to keep pace with the light-speed nature of the book trade now, maybe we should sync with the future and move our clocks forward every week, every day, every hour, every minute (while simultaneously living in the present and honoring the past).

Changing the clocks back an hour from Daylight Saving Time last weekend felt like using a sundial, and made me think we need more times: Present Saving Time, Past Saving Time, Future Saving Time. And if we're going to keep pace with the light-speed nature of the book trade now, maybe we should sync with the future and move our clocks forward every week, every day, every hour, every minute (while simultaneously living in the present and honoring the past).

Over the years, most of us have attended or participated in conference and trade show panels that addressed the "future" of the book, of the book trade, and of bookselling. We continue to do so, but what we're really discussing isn't so much the future as time itself.

In Books: A Manifesto, Ian Patterson observes that "the more you think about novels, the more impossible it becomes to ignore thinking about time. Novels are all about time: they take time, and make time, but the imagined time you inhabit as you read them is just that, imagined, illusory, a fictional time confirmed within the parameters of a book.... Time in the novel, the time of the novel in the reader's mind, the time the novel takes to read, the long or short stretches of imagined time the reading gives rise to, all these complex interior responses live alongside the changes reading and books go through in time, in history."

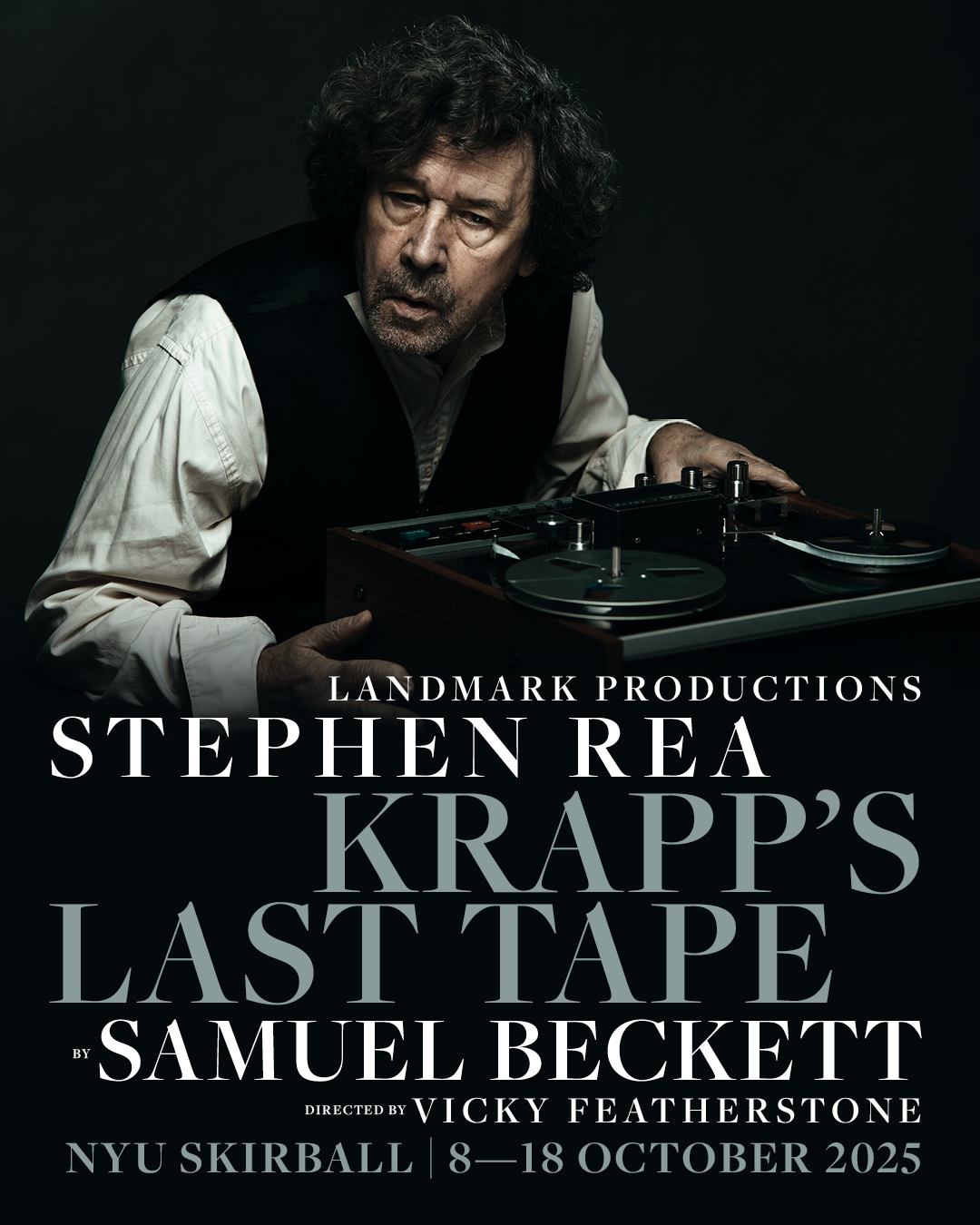

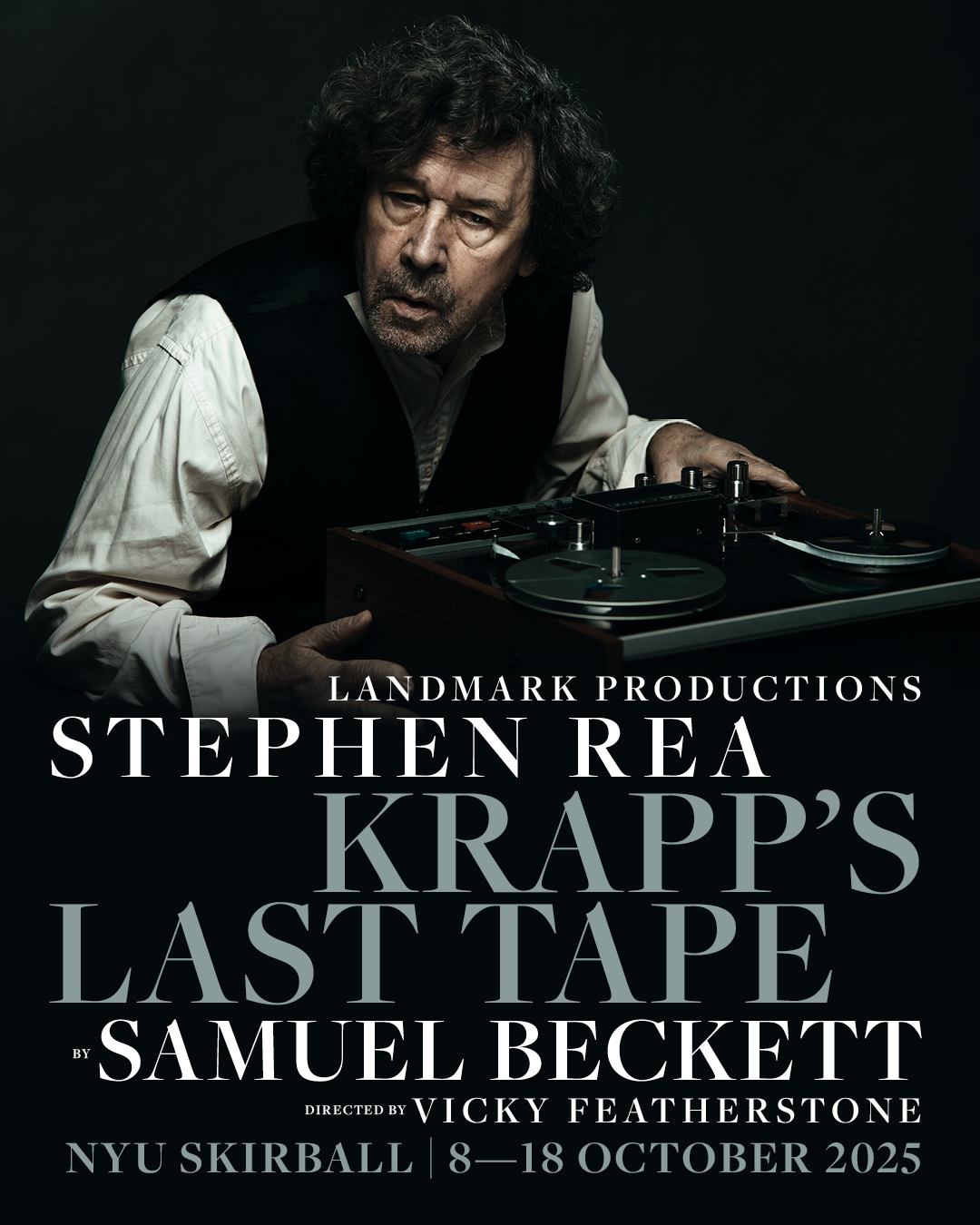

My sense of book time was heightened a few weeks ago when I saw a production of Samuel Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape at New York University's Skirball Center. Starring Irish actor Stephen Rea and directed by Vicky Featherstone, the play centers on a 69-year-old man confronting his past by listening to old reel-to-reel tapes he has recorded on his birthday over the decades, and particularly one from 30 years previously.

Beckett wrote the play in 1958, and its "technology is rooted in that time, when tape recorders first became popularly available, so he set it 'in the future,' as his script notes--because Krapp needs to have been recording himself for most of his life," the New York Times noted. "Our technology is different now, our tendency to self-tape completely out of control, but mortality still threatens. This lean-in contemplation of it is timed just right for our too-short attention spans: 55 minutes, at the end of which you'll have added a classic to your day. Do."

Beckett wrote the play in 1958, and its "technology is rooted in that time, when tape recorders first became popularly available, so he set it 'in the future,' as his script notes--because Krapp needs to have been recording himself for most of his life," the New York Times noted. "Our technology is different now, our tendency to self-tape completely out of control, but mortality still threatens. This lean-in contemplation of it is timed just right for our too-short attention spans: 55 minutes, at the end of which you'll have added a classic to your day. Do."

One of the annoying things about the future is that it's... unforeseeable. Maybe that's why we're amused by the past and its quaint ways. In the movie The Time Machine, Weena shows the Time Traveler talking rings:

"They speak?" he asks.

"Yes."

"Of what?"

"Things no one here understands."

Weena takes a ring from him, places it on its edge like a coin, and spins it on the smooth surface of a stone table. A disembodied voice fills the hall: "My name is of no consequence. The important thing you should know is that I am the last who remembers...." Talking rings don't exist in H.G. Wells's 19th-century novella. They were an imagined invention from the far distant future invented for a mid-20th century movie, but the concept already seems technologically antiquated.

Weena takes a ring from him, places it on its edge like a coin, and spins it on the smooth surface of a stone table. A disembodied voice fills the hall: "My name is of no consequence. The important thing you should know is that I am the last who remembers...." Talking rings don't exist in H.G. Wells's 19th-century novella. They were an imagined invention from the far distant future invented for a mid-20th century movie, but the concept already seems technologically antiquated.

In the book trade, it's the present that sometimes feels like it is "beyond our wildest dreams" (the false promise of any future), but bookish folk have always toiled in the future (reading ARCs of books that won't be published for months) as well as the past (well, most books). We are time travelers, too.

More than a decade ago, author China Miéville wrote in the Guardian: "Futures of anything tend to combine possibilities, desiderata, and dreaded outcomes, sometimes in one sentence. There's a feedback loop between soothsaying and the sooth said, analysis is bet and aspiration and warning. I want to plural, to discuss not the novel but novels, not the future, but futures. I'm an anguished optimist."

Turn the clocks back further, to the fall of 2007. On my Amtrak trip north from Baltimore after NAIBA's Fall Conference, time was on my mind: the time that seems, in every age, to be shrinking even as we discover technological breakthroughs meant to make more efficient use of time.

At the conference, I'd been on an Internet marketing panel led by Jessica Stockton Bagnulo, then events coordinator at McNally Robinson in New York City (now owner of Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn) and creator of The Written Nerd blog. The panel explored bookstore websites, blogs, and possible online strategies for booksellers.

During q&a, the subject of time management came up as a key impediment to engaging more creatively with Web 2.0 opportunities: If everyone was already working at full tilt, how could they incorporate online marketing into the mix? Where in the course of their busy days would they find time to blog, to update website staff picks, to send out e-mail newsletters, to check and fulfill online orders?

Almost two decades have passed since then. A hundred trade show panels couldn't fully answer these questions because book time is elusive. When booksellers were slipping index cards between the pages of books for inventory control, there wasn't enough time. What were we doing with all our extra time before we had to answer e-mails, texts, and cell phone calls all day?

Fortunately for us, book time continues to be found where we've always found it, in its devilish expandability.

Turner said, "The goal is simple, give romance readers in the community a place to belong." Morally Gray will host community events, monthly book clubs, and offer a space for local authors and merch creators to share their work.

Turner said, "The goal is simple, give romance readers in the community a place to belong." Morally Gray will host community events, monthly book clubs, and offer a space for local authors and merch creators to share their work.

Currently located at 515 E. State St., Nature + Nurture will be moving to a building at 553 E. State St. that store owner Tricia Ross has purchased. The bookstore will double in size, with Ross planning to create an events space as well as room for customers to relax and read. The new building also has on-site storage space, office space, and a loading dock in the back.

Currently located at 515 E. State St., Nature + Nurture will be moving to a building at 553 E. State St. that store owner Tricia Ross has purchased. The bookstore will double in size, with Ross planning to create an events space as well as room for customers to relax and read. The new building also has on-site storage space, office space, and a loading dock in the back.

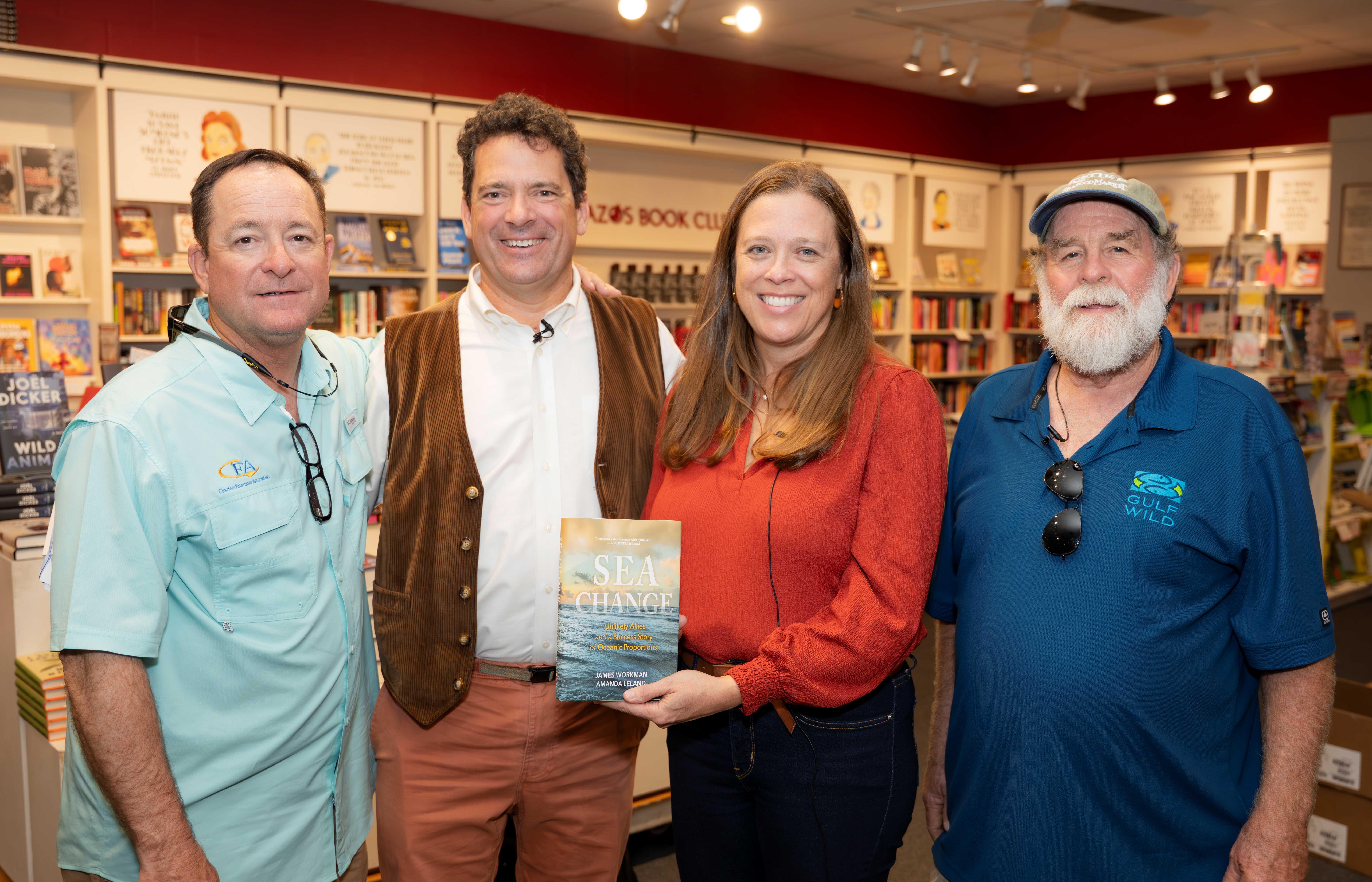

James Workman (second from left) and Environmental Defense Fund executive director Amanda Leland (third from left), co-authors of

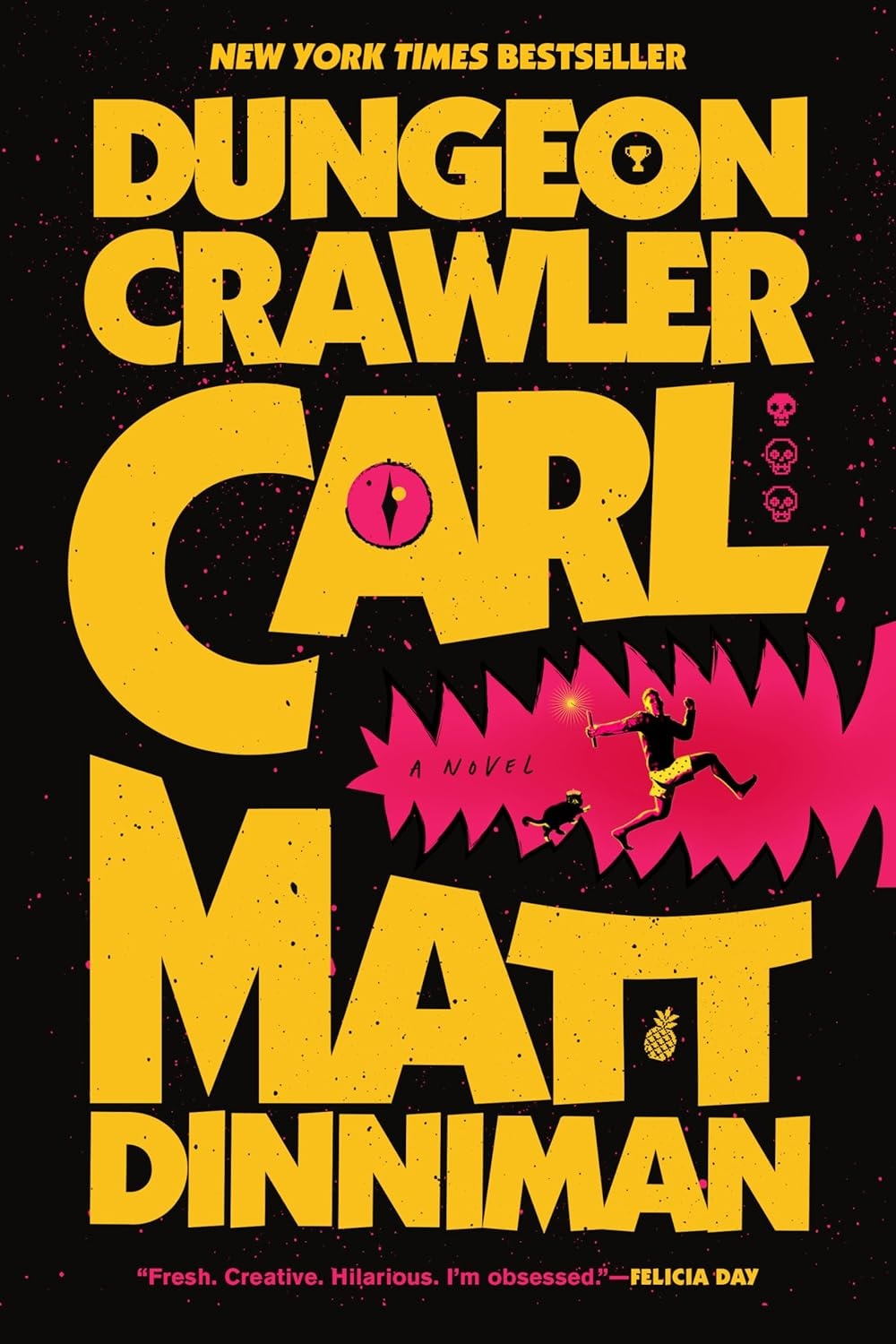

James Workman (second from left) and Environmental Defense Fund executive director Amanda Leland (third from left), co-authors of  Books-A-Million has selected Dungeon Crawler Carl by Matt Dinniman (Ace) as its inaugural Book of the Year pick, which "recognizes the title that best embodies the joy of reading and the enthusiasm of Books-A-Million's team." Impetus for the selection came from Olivia McDaniel, v-p of marketing, "whose love for the series inspired an internal book club and a wave of new fans across the company."

Books-A-Million has selected Dungeon Crawler Carl by Matt Dinniman (Ace) as its inaugural Book of the Year pick, which "recognizes the title that best embodies the joy of reading and the enthusiasm of Books-A-Million's team." Impetus for the selection came from Olivia McDaniel, v-p of marketing, "whose love for the series inspired an internal book club and a wave of new fans across the company."

How to Teach a Monster

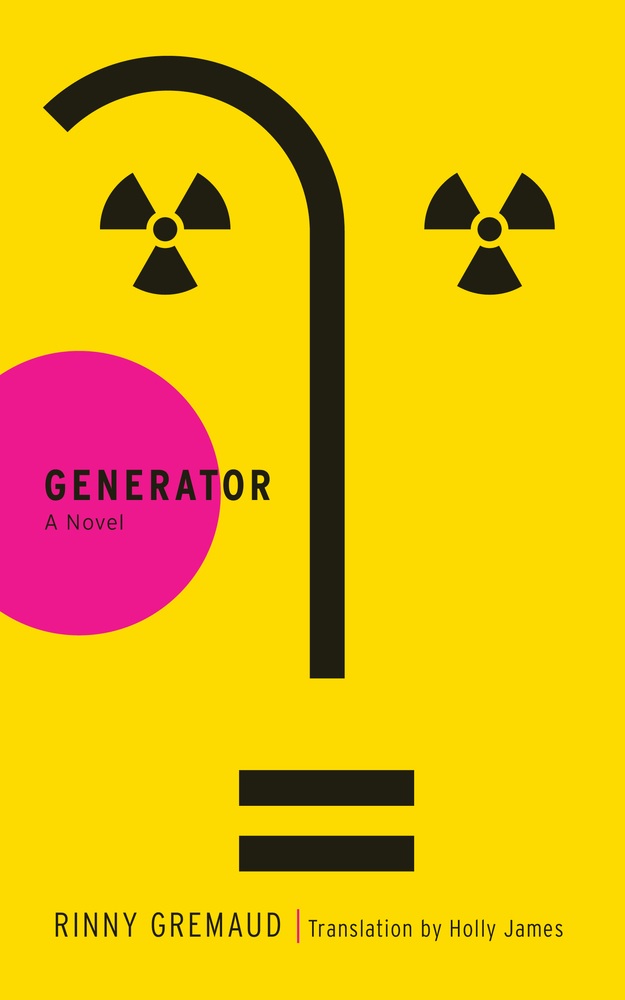

How to Teach a Monster Korean Swiss journalist Rinny Gremaud's debut novel, Generator, provides a deeply meditative examination of identity--"relative, if not fluid"--provocatively conflating nuclear power with biological ancestry. Holly James smoothly translates from the original French. In 1977, the narrator was born at Kori, the site of a nuclear power plant in Busan, Korea. Her Korean mother's English fluency got her a job with a British company, where she met her daughter's father, a British engineer. Once reactor Kori 1 was complete, however, the father left Korea, abandoning mother and child.

Korean Swiss journalist Rinny Gremaud's debut novel, Generator, provides a deeply meditative examination of identity--"relative, if not fluid"--provocatively conflating nuclear power with biological ancestry. Holly James smoothly translates from the original French. In 1977, the narrator was born at Kori, the site of a nuclear power plant in Busan, Korea. Her Korean mother's English fluency got her a job with a British company, where she met her daughter's father, a British engineer. Once reactor Kori 1 was complete, however, the father left Korea, abandoning mother and child.

Changing the clocks back an hour from Daylight Saving Time last weekend felt like using a sundial, and made me think we need more times: Present Saving Time, Past Saving Time, Future Saving Time. And if we're going to keep pace with the light-speed nature of the book trade now, maybe we should sync with the future and move our clocks forward every week, every day, every hour, every minute (while simultaneously living in the present and honoring the past).

Changing the clocks back an hour from Daylight Saving Time last weekend felt like using a sundial, and made me think we need more times: Present Saving Time, Past Saving Time, Future Saving Time. And if we're going to keep pace with the light-speed nature of the book trade now, maybe we should sync with the future and move our clocks forward every week, every day, every hour, every minute (while simultaneously living in the present and honoring the past).  Beckett wrote the play in 1958, and its "

Beckett wrote the play in 1958, and its " Weena takes a ring from him, places it on its edge like a coin, and spins it on the smooth surface of a stone table. A disembodied voice fills the hall: "My name is of no consequence. The important thing you should know is that I am the last who remembers...." Talking rings don't exist in H.G. Wells's 19th-century novella. They were an imagined invention from the far distant future invented for a mid-20th century movie, but the concept already seems technologically antiquated.

Weena takes a ring from him, places it on its edge like a coin, and spins it on the smooth surface of a stone table. A disembodied voice fills the hall: "My name is of no consequence. The important thing you should know is that I am the last who remembers...." Talking rings don't exist in H.G. Wells's 19th-century novella. They were an imagined invention from the far distant future invented for a mid-20th century movie, but the concept already seems technologically antiquated.