Hand in Hand: Ten Black Men Who Changed America

by Andrea Davis Pinkney, Brian Pinkney, illus. by Brian Pinkney

Andrea David Pinkney (Sit-In: How Four Friends Stood Up by Sitting Down) gives young readers a sweeping history made personal through the individual biographies of 10 African American men, stretching from Benjamin Banneker in 1731 through to President Obama today.

Because Pinkney includes differing points of view--in particular W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington in the mid–19th century, and Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. in the mid–20th century--young people may examine for themselves the arguments for a separate black society versus integration, and come to their own conclusions. Pinkney also lays out how Frederick Douglass, at the turn of the 19th century, provided the foundation for the debates between these two pairs of men. Because he believed in equality for all human beings, Douglass was also a champion for women's rights. The author engages young people to think critically about their ideas, where they contradict one another, where they coincide, and how each was shaped by his early life, culture and society.

What all 10 share in common is their passion for reading--and writing. Benjamin Banneker's Almanac, published in 1792; Booker T. Washington's Up from Slavery; W.E.B. DuBois's 15 essays in The Souls of Black Folk, which, we read later in the volume, had a profound effect on both A. ("Asa") Philip Randolph and Barack Obama. Randolph founded and reported for the newspaper the Messenger and Barack Obama wrote two books, Dreams of My Father and The Audacity of Hope. Even in Jackie Robinson's biography, which focuses on how his pursuit of baseball changed America, Pinkney discusses what an outstanding student he was.

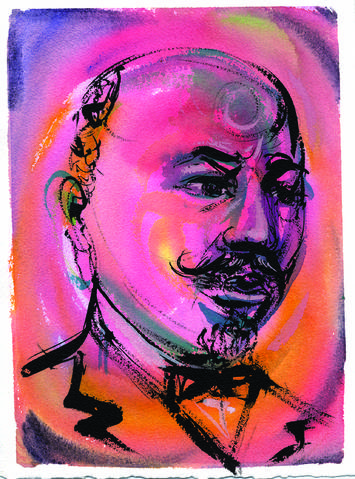

Pinkney's narrative voice evokes the oratory power of these men, many of whom took to the soap box or pulpit. She refers to Frederick Douglass's Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave as a "sermon in script" and writes, "When he preached, it was as if thunder was stomping its feet." A. Philip Randolph, who had yearned to become an actor and often stood on book crates to address crowds in Harlem, realized, "If he was seeking an audience and standing ovations, he needed to stand for something." Brian Pinkney's watercolor portraits evoke the spontaneity of sketches, resulting in deeply psychological renderings of each of the 10 men. Vignettes in each chapter highlight a milestone event--a Pullman Porter's cap to signify Randolph's role in negotiating the porters' labor agreement with the Pullman Company; a line of citizens walking past a bus in Montgomery, Ala., symbolizes Dr. King's leadership in the bus boycott there.

We also see their early childhood influences. An enslaved six-year-old Booker T. Washington, carrying the books of the master's daughter to school, longs to become educated and eventually founds the Tuskegee Institute. Thurgood Marshall--whose great-grandfather caused so much trouble that the plantation owner finally set him free--inherited the troublemaker gene. As punishment for the pranks he played in grade school, young Thurgood's principal sent him off to the school's basement to memorize passages from the Constitution. Young Thurgood committed the entire thing to memory before his grade school years were through. Did this lead him on the path to becoming the first African American Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court? Young readers can decide that for themselves.

Many of these 10 also had audiences with U.S. presidents. A. Philip Randolph had two audiences--first, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who introduced the Fair Employment Act to address one of the main issues around which Randolph was organizing a march in 1941. Then, two decades later, with Randolph's assurances to President Kennedy that his protestors would remain nonviolent, Kennedy gave his blessing to the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech.

Hand in Hand shows us the personal journeys of each man and how their passions and convictions help further the dreams of those who followed. Malcolm X and Thurgood Marshall each found ways to turn their lives around, using their discontent to examine their circumstances and figure out how to make changes in themselves and the world around them. W.E.B. DuBois, with his Pan-Africanism, and Malcolm X, with his Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), had similar goals, to expand their movements into a global effort to achieve racial equality. Each individual journey stands alone, and together they paint a full portrait of the path of African Americans and United States history through nearly 400 years.

Young people will come away from this beautifully designed volume believing that they can be part of the change they want to see in their world. Where they see injustice, unfairness, poverty or faithlessness, they will be inspired to take action to remedy the situation. --Jennifer M. Brown

Andrea Davis Pinkney is a versatile author whose work ranges from the novel Bird in a Box, a Today Show Al Roker Book Club Pick, to her picture books with her husband, Brian Pinkney: Sit-In: How Four Friends Stood Up by Sitting Down, which was named a 2011 Flora Stieglitz Straus Award winner and a Jane Addams Honor book; and Duke Ellington: The Piano Prince and His Orchestra, which received a Caldecott Honor. She and Brian Pinkney live with their family in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Andrea Davis Pinkney is a versatile author whose work ranges from the novel Bird in a Box, a Today Show Al Roker Book Club Pick, to her picture books with her husband, Brian Pinkney: Sit-In: How Four Friends Stood Up by Sitting Down, which was named a 2011 Flora Stieglitz Straus Award winner and a Jane Addams Honor book; and Duke Ellington: The Piano Prince and His Orchestra, which received a Caldecott Honor. She and Brian Pinkney live with their family in Brooklyn, N.Y. Years ago, I had gone to W.E.B. DuBois's grave and living space in Ghana, in West Africa. I remember at the time feeling that this man and his mission have inhabited me for the time that I've been here. And then, Brian and I were driving in Great Barrington, Mass., and we said, "Look, there's W.E.B.'s boyhood home." I experienced again that same quivering feeling. Each of them inhabited me in the process of writing each of their individual stories, and basically gave me the narrative. Then you go back, you edit, you make the transitions and all that. But each one came like a bolt.

Years ago, I had gone to W.E.B. DuBois's grave and living space in Ghana, in West Africa. I remember at the time feeling that this man and his mission have inhabited me for the time that I've been here. And then, Brian and I were driving in Great Barrington, Mass., and we said, "Look, there's W.E.B.'s boyhood home." I experienced again that same quivering feeling. Each of them inhabited me in the process of writing each of their individual stories, and basically gave me the narrative. Then you go back, you edit, you make the transitions and all that. But each one came like a bolt.