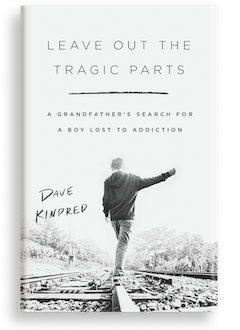

Leave Out the Tragic Parts: A Grandfather's Search for a Boy Lost to Addiction

by Dave Kindred

Heartbreaking and eye-opening, Leave Out the Tragic Parts: A Grandfather's Search for a Boy Lost to Addiction is award-winning journalist Dave Kindred's (Sound and Fury) memoir about the devastating impacts of alcoholism, the indominable spirit of a boy born to wander, and the ways love both blinds and allows unconditional understanding.

When Kindred received the news--"Jared died"--about his grandson, he wept. He had lost a boy he'd known since birth and a young man he hadn't known at all--one who went by "Goblin" and hopped trains, wandering the U.S. as a "travelin' kid." At Jared's funeral, Kindred met some of his grandson's traveling companions--"road dogs"--and listened to them reminisce. "The best time of my life," one named Maggie said. "Goblin was everywhere's sunshine," said a girl named Aggro. And so, they spurred the difficult work that would culminate in Kindred's Leave Out the Tragic Parts.

Kindred lived across from his son's family for much of Jared's childhood. Jared gave him "a second chance of sorts at fatherhood"; as a sports columnist, Kindred had rarely been home to spend time with his son. But after several relocations, his parents' "nasty divorce," and being separated from his twin brother, Jared began drinking. He was 13 years old. Two years later, he confessed to being an alcoholic. "We let it pass, though," Kindred remembers, "because what could a fifteen-year-old know about being an alcoholic?"

After high school, Jared was gone, living life on the road. He hopped his first trains with a 17-year-old calling herself Stray Falldowngoboom, and the two drank "a lake's worth of vodka" as they traveled 2,000 miles to New Orleans. And it would be to this city, with its "orgies of liquid and flesh," that he was drawn following a hospital stay for alcohol withdrawal. "The addiction demanded to be fed," Kindred explains. After numerous, increasingly concerning hospital stays, Jared's mother posed what should have been a sobering question: "Do you want to be buried or cremated?"

Engrossing in its careful construction, Kindred's part-memoir, part-biography moves between defining moments in Jared's and Kindred's lives. Kindred recalls his own role in Jared's life as Goblin--chatting about naked girls, wiring him money, urging him to quit drinking--and effectively intertwines his personal history into the narrative. He ties regrets about his deceased father to his drive to honor his dead grandson, connecting his mother's kindness toward hoboes to Jared's path, and recognizing his own "wanderer's instinct" in his grandson.

Goblin's tale unfolds via his road dogs, sometimes in their own words but primarily through Kindred's first-rate, passionate storytelling. Though an unrelenting love guides his reporting, the gut-punching power behind each page lies in its unfiltered truth. In a vulnerable and admirable approach, Kindred wields his renowned journalistic perspective, sidestepping the story he'd prefer to tell--the one with the tragic parts left out--to reconstruct every step that led to his grandson's death at age 25.

Kindred's desire to elucidate the realities of addiction fuels his stirringly honest prose. Startling scenes reveal the desperation alcohol bred in Jared--sleeping with vodka beside him to keep DTs at bay, trying to drink his own urine while detoxing because he thought it contained alcohol, walking through a hurricane to seek "immediate relief from withdrawal." Citing experts on drug abuse and mental health, Kindred takes a clear stance that addiction is a disease. "It literally rewires your brain," he notes. "The substance owned him."

Though his family knew Jared was losing a battle, their varied attempts to help couldn't match the strength of his opponent. "He wasn't Jared anymore," his twin told Kindred, one impetus for Kindred's adamancy about heeding early warning signs. After his stepmother convinced him to enter rehab, Jared backed out at the last minute. "The addict says it all to make everyone feel better, to give everyone hope, to give himself hope," Kindred says, highlighting how even caring family cannot change an addict's mind, both because addicts view "the substance as a nutrient" and because loved ones want to believe "something good" can course-correct them.

But through it all, Jared "never put the substance above friends." Uplifting words from his road dogs add a brightness and paint a vivid portrait of an endearing young man. They describe his tenderness: how they could nuzzle against his chest, how he prevented their dehydration by finding prickly pear cactuses, how he helped a lost kid in New Orleans, how he kept an injured hobo from killing himself. They laud his chivalrous, charismatic, "train-hopping Jesus" nature. "He made my heart light with laughter and love," says one friend. "Goblin was a soul that was meant to just keep going," says another. Maggie, who would have married Jared in a "heartbeat," calls him the "happiest guy [she'd] ever seen."

With compelling reporting and emotional interviews, Kindred invites readers into Goblin's world of despair and sunshine. Leave Out the Tragic Parts is impossible to forget. It is an enduring saga of a remarkable life--one that will instill empathy for victims of addiction, foster understanding of homeless individuals, and inspire awe at how strongly one young man could touch so many hearts. --Samantha Zaboski