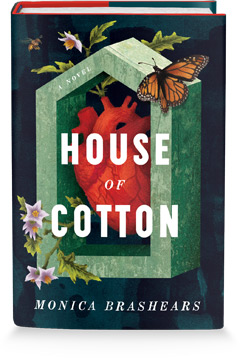

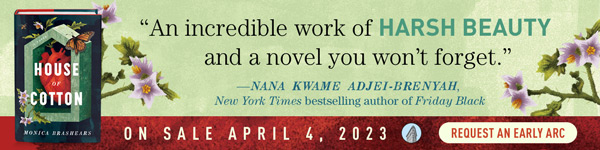

House of Cotton

by Monica Brashears

Monica Brashears's House of Cotton is an engrossing coming-of-age novel about ghosts, mothers and the struggle to survive. It is also a novel of the lingering challenges of race and class. Brashears's prose style is sharp and incisive, and the entrancing, distinctive voice of her protagonist is by turns weary, sardonic and yearning. A haunting story and unusual perspective make this a memorable and thought-provoking debut.

Magnolia Brown is 19 years old when her grandmother, Mama Brown, dies. Her absent mother struggles with substance abuse and an abusive partner, so that leaves Magnolia more or less alone in the world, fending off a lecherous landlord (who is also deacon at her grandmother's church) and struggling to get by. She works the night shift at a Knoxville, Tenn., gas station, where she tries to care for Cigarette Sammy, the muttering man who goes through the trash outside ("the only other Black person I see on this side of town"), between one-and-done encounters executed by her Tinder persona, Carolina Nettle. It's a tenuous living, and she misses Mama Brown terribly. One night "a whistling man with blood-smeared hands" walks into the gas station. "Hearing a man whistle when he walks in a place he don't own ain't natural. Like finding a chipped tooth on concrete. An omen." When he returns from the bathroom after cleaning his hands, she sees the man is polished, manicured, smooth-talking, wearing good cologne. Cotton offers Magnolia a modeling job, but she's wary; Magnolia knows omens. But she's also broke, and quite possibly pregnant.

At the address he gives her, Magnolia finds the Weeping Willow Parlor, a funeral home run by Cotton and his gleefully friendly, drunk Aunt Eden. The pair is eccentric: Cotton needs to constantly finger a piece of pocketed twine to remain calm; Eden is something of an alcoholic and firmly does not believe in ghosts. They are wealthy, and culturally foreign to Magnolia.

Cotton and Eden Productions offers Magnolia a most unusual modeling job: they provide families with lost or missing loved ones a final contact, a side business something like a séance. With Eden's uncanny funeral-home makeup skills and Magnolia's amateur acting, Magnolia will play the part of the dead. She's used to pretending, it has long been her coping mechanism: "When I get this way, when I feel like kudzu is wrapped tight around my ribcage and I'm bleeding a bright heat, I like to slip inside my head." She slides smoothly into Cotton and Eden's world and their comfortable, decadent habits: cocktails at all hours, joyriding in the hearse. She moves into the funeral home, lets Eden apply pale body paint to allow her to become missing white women and men, and begins saving her money. The ghost of Mama Brown checks in with Magnolia: knowing, comforting, but judging as well. Reading a letter Mama Brown left her, Magnolia knows "[S]he ain't left me. I ain't seen her, but she sits by me. Unseen but real as humidity." Soon the ghost will be seen as well.

Magnolia's life becomes split. At the Weeping Willow, she lives in ease and has money to spare, but feels estranged from the very different world Cotton and Eden come from. The relationship is transactional, and she's always acting, even when the makeup is off. And then there is Mama Brown's home, where the garden (the place Magnolia still meets her Tinder dates) grows out of control. By tending the needs of the rich white folks who help support her, Magnolia has literally let her own house get out of order. Her caretaking of Cigarette Sammy has become disrupted. Cotton's requests get weirder and weirder, and Mama Brown's ghost expresses concerns about Magnolia's choices, which have affected Mama Brown in the afterlife. The worldly and otherworldly pressures mount.

Set in the grand Weeping Willow Parlor, complete with secret passageways and haunted by Magnolia's much-loved but literally disintegrating grandmother, House of Cotton pits traditional gothic elements (the haunted castle, women in distress, death and decay) against contemporary questions about race and class and the persistent legacy of slavery. It shares the genre's sense of suspense and foreboding, but Magnolia's struggles are very realistic. Her first-person narration brings an immediacy to the events, and an intimacy that's advanced by her frank voice and turns of phrase. On its face, this is an intriguing ghost story with a compelling, beleaguered protagonist. In its layers, there is much more at stake.

"I am a tattered quilt of all the women before me. I am a broken puzzle," Magnolia states, but she is clearly a survivor as well. Despite her many fears, she is somehow fearless in pursuing the truest version of herself. Brashears excels in strong characters and deeply felt emotions, and in a robust sense of place: Knoxville shines as both urban and cultural setting and in the details of its natural world. Brashears offers a fresh new perspective on Appalachia and the American South, and Magnolia's rich voice will echo with readers long after the pages are closed. --Julia Kastner