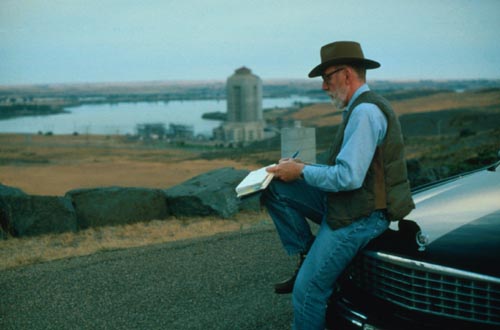

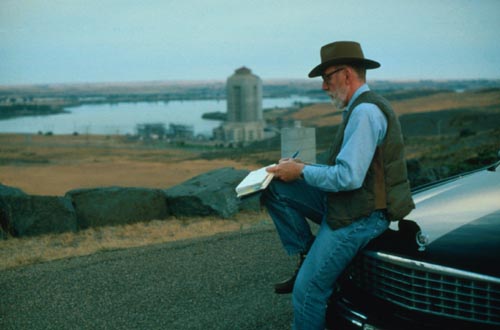

Although Ivan Doig has lived in Seattle for a very long time, he maintains that Montana is still the home of a piece of his soul. The vividness of his early life there has been forever imprinted on him, even though he left at age 23. He has been back several times through the years, usually on work and research related trips. Readers who have never been to Montana will certainly gain a real sense of it in Doig's writing; those who have will feel at home on the page. As Doig spins out his yarns, the stories take precedence and the landscape becomes important background.

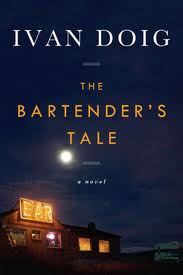

In English Creek, Bucking the Sun and Eleventh Man, we met Tom Harry, the bartender with the black pompadour. In The Bartender's Tale (see our review below), he is the eponymous bartender, father of Rusty ("an accident between the sheets") and owner of the Medicine Lodge bar. Tom has brought six-year-old Rusty home to Gros Ventre from his sister's house in Arizona, where he was left when Tom's wife walked out. The real story begins the summer of 1960, when Rusty is 12.

How did you fit yourself so completely into the mind of a 12-year-old boy?

I wasn't much older than Rusty-- a freshman in high school--when I was living along the Rocky Mountain front, north of Great Falls, running sheep on a ranch, living with a family who ran a cafe much like the one in the book. That community of Dupuyer--close in feeling and geography to the setting in the book-- was part school, part ranch family and part town. Those memories are still available to me today. It was a strange mix of old timers, cafe folks and ranchers. One of the guys was an old trapper who made his living trapping in the Rockies.

Talk about your day, writing and not writing.

I get up before dawn, following the rancher's life, start writing by six, then Carol (my wife) and I take a walk around 7 a.m. We walk for 45 minutes and I count on a word or an idea coming to me as we climb a big hill toward home. Something that will relate to, expand on or improve what I've started that day. I look over all parts of speech, starts of paragraphs, chapter beginnings, trying to hear the characters' voices and the rest of the story. Then I sit down and write until lunch. I produce roughly two triple-spaced pages of typescript a day--400 to 500 words. And, yes, I work on a Royal manual typewriter, something I have hidden occasionally, lest I be taken for a Luddite. (I sent an article about that off to my editor in New York just this morning.) I also use a computer and a yellow pad, especially when I am roughing out dialogue. I am an equal opportunity writer, making good use of all implements available.

Fourteen years ago, when Carol retired, we bought this big house on a bluff. She runs the house, fields e-mails and is still my first reader. She is my amanuensis par excellence. It is a lot of house, a lot of property and a lot of gardening and yard work. That takes up much of our time. We have a vegetable garden, fruit, apple trees. I learned grafting because our apple trees produced inedible and unidentifiable fruit. I grafted on four edible species. Much improved.

Did you always know that this was what you would do?

Did you always know that this was what you would do?

It struck me early on that the life of the lesser sharecropper was a fight against heavy weather odds. My Dad urged me to get an education, not to do outside work. He joined forces with my grandmother after my mother's death; he as a general ranch hand and she as a cook, so we all knew the stories of the sheepherders who work, come to town, get drunk, go out and work again. I got a Bachelor's degree in Journalism and then a Master's degree and have written ever since.

One of the irresistible parts of The Bartender's Tale is the schtick that Rusty and his friend Zoe do: "bits" that they concoct out of thin air, dialogue made up out of whole cloth. Where did this theater knowledge come from?

Well, I hung out with some theater types in college, and Book-It Repertory Theatre in Seattle did Prairie Nocturne, which brought us in touch with more theater folks. It is an interest of ours.

As a writer of realism, you seldom use symbolism, yet right at the beginning of the book is the marvelous symbol of Igdrasil, the Norse Tree of Life. Where did that come from?

It came immediately to mind because it gives the feel of the country filled with giant cottonwoods around Choteau--Gros Ventre in the book. A 99-year-old friend of ours told me the story of Igdrasil more than 20 years ago. Carol took her a copy of the book just today.

Can't let you off the hook about some offhand references to Charlie Russell and fly fishing--two Montana icons that you seem not to take too seriously.

We fished to eat; lots of worms and chicken guts in the mix, not much romance. Indeed, Charlie Russell is the iconic Montana painter.

What's next?

Next up is a sequel to Work Song, set in Butte in 1921. If all is in proper alignment, it could be out next year. --Valerie Ryan, Cannon Beach Book Company, Ore.

Ivan Doig: Montana, Apple Trees and a Typewriter

In May We Be Forgiven by A.M. Homes (Viking, Sept. 27), the life and extraordinary times of Richard Nixon scholar Harry Silver are deftly chronicled, including a Sisyphean quest--perhaps the least of his challenges in the story--that puts him in the discomforting, if entertaining, position of teaching Nixon to undergrads who "sit unblinking in a stupor."

In May We Be Forgiven by A.M. Homes (Viking, Sept. 27), the life and extraordinary times of Richard Nixon scholar Harry Silver are deftly chronicled, including a Sisyphean quest--perhaps the least of his challenges in the story--that puts him in the discomforting, if entertaining, position of teaching Nixon to undergrads who "sit unblinking in a stupor."  Eduardo Halfon's brilliant novel The Polish Boxer (Bellevue Literary Press, Oct. 2) opens with one of the best classroom scenes I've ever read. The professor, a Guatemalan writer and literature instructor, stands helplessly before row upon row of students looking "like lost sheep, yet smugly convinced that they weren't."

Eduardo Halfon's brilliant novel The Polish Boxer (Bellevue Literary Press, Oct. 2) opens with one of the best classroom scenes I've ever read. The professor, a Guatemalan writer and literature instructor, stands helplessly before row upon row of students looking "like lost sheep, yet smugly convinced that they weren't."

Did you always know that this was what you would do?

Did you always know that this was what you would do? Shannon Hale

Shannon Hale