Katherine Marsh was born exactly as charted by an astrologer whom her mother, then 30, consulted back in the 1960s. The astrologer predicted that her mother would have a girl late in life, and that she'd be a Scorpio. Marsh struggled with the idea of fate but also believed she could make her own decisions. "That struggle was something I wanted to write about," said Marsh. "I did some research and discovered there was this time when science and astrology were one and the same." That time is the 16th-century setting for Jepp, Who Defied the Stars.

Katherine Marsh was born exactly as charted by an astrologer whom her mother, then 30, consulted back in the 1960s. The astrologer predicted that her mother would have a girl late in life, and that she'd be a Scorpio. Marsh struggled with the idea of fate but also believed she could make her own decisions. "That struggle was something I wanted to write about," said Marsh. "I did some research and discovered there was this time when science and astrology were one and the same." That time is the 16th-century setting for Jepp, Who Defied the Stars.

Did you base Jepp on a historical person?

Yes. I became fascinated with Tycho Brahe (pronounced TEAK-o BRA-hay). He had a castle with running water, which no one else had, a prosthetic nose and a dwarf jester named Jepp. I thought, he'd be such an interesting observer of this world. As a dwarf, he'd believe in fate and his life being determined by his form. Jepp is a footnote [in Brahe's story], but that's a great entry as a novelist.

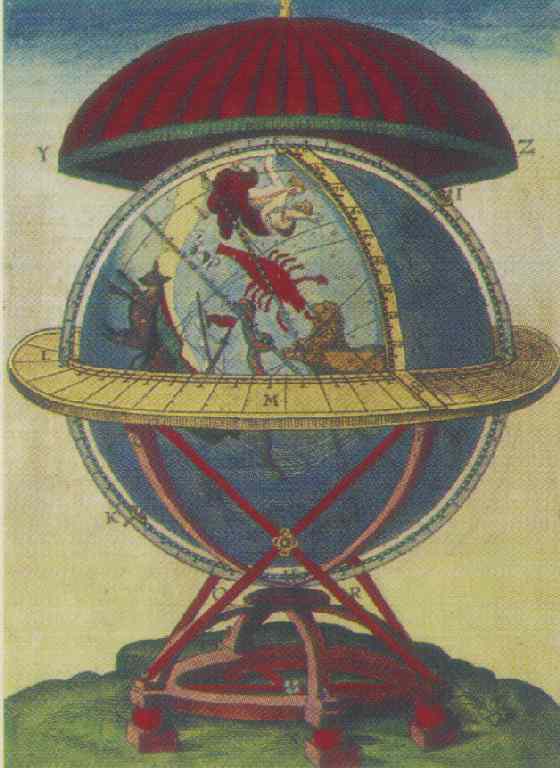

Tell us more about Tycho.

He was both an astrologer and an astronomer. He drew up charts for the King of Denmark. He also struggled with fate and free will. Jepp discovers a book Tycho had written, in which he finds "Elegy to Urania." In it, Tycho writes, "few will take the way of the mind on earth,/ So, very few can bend the heavenly force." That really is Tycho's poem. He really struggled himself with these issues. He struggled with alchemy, too. He was smack in the middle of this debate.

That also goes to the heart of the Renaissance, doesn't it?

That also goes to the heart of the Renaissance, doesn't it?

I wanted to capture that feeling of awe, the scene when Jepp gets to go up to the observatory--that moment of discovery, seeing the heavens.

For Jepp, that's the moment when science and faith intersect.

As I was writing the book, I thought, "This is a quirky personal story," but there are still these resonances that we're grappling with today, these questions of science and faith that we wrestle with. Getting back to astrology, there's the question of how to live in an uncertain world. For Jepp. If you accept some of the science and get away from some of the faith, you realize there's wholeness in the universe. How do you look at the world with a clear eye and still find comfort in it?

The story starts out with this question of who Jepp's father is. It's a search for a father, then a much larger search: What do our origins say about who we are and what we can be?

How did you find Jepp's narrative voice? The syntax is just antiquated enough so we know that he's from another time, yet it's still accessible.

I first just sat down and tried to write from his perspective and get it in my head. It is a first-person book and he carries it. I went off into the etymological dictionary, and I tried not to use words that came into use after 1600. I also read some of Tycho's letters and used them when I was composing letters between Jepp and Magdalene.

How did you land on the idea of flashbacks to fill in life before Jepp arrives at Tycho's household?

I wanted to pull people right into it: Here's Jepp, he's in trouble, and he doesn't know where he's going. At the point we meet him, he's had some education, he's seen the larger world, he's had some disappointments. The first part of the book is largely flashback, though we see him moving toward something. The second part is the heart of the book. I wanted to get to Tycho's castle. There I felt I could slow down and be in the present. The third part ties up all the threads of the first two.

Tell us about Magdalene Brahe, Tycho's daughter.

Magdalene is an interesting mix of being bold and unconventional, yet she has an inner terror of being displaced. She's spent her life on this island, in a way she's less experienced than Jepp. She's a huge help to him because she has a confidence he doesn't. I wanted there to be a first love, Lia, and a second love that's deeper, richer and more surprising. First love, it turns out you're more in love with your idea of that person--you're more in love with yourself than the other person. In the beginning he doesn't like Magdalene. The intellectual sparks call up the romantic ones. They don't agree. That's what makes them such an interesting couple.

Magdalene's comment to Jepp regarding Lia's fate--"If you love someone, you must believe that they know what is best for themselves"--gives Jepp permission to forgive himself.

One of the other themes of the book is this idea of forgiveness. There are a lot of wonderful things in the world, and it's uncertain, but if you go in with compassion and forgiveness, there's much to look forward to. Growing up is about making mistakes. And Jepp forgives others, but he has to also forgive himself. I want readers to debate a lot of things, debate the ending, debate did Jepp do the right thing by Lia? Closure and forgiveness are important for Jepp, regardless of whether you think he did something wrong or not.

Magdalene also asks Jepp, "Is it not our imperfections that forge our characters?"

That's the moment when he accepts being a dwarf. He grew up in a loving household and he didn't see himself differently. But as he gets older, he feels a sense of alienation. When he starts to see that as a strength, it's a turning point. Your weaknesses are your strengths, and your strengths are your weaknesses. One of the things I do like about astrology is this idea that even if you have a good chart, it can make you an indolent person, and if you have a weak chart, you develop strengths to overcome them. Everybody has fate, in that you're born into a set of circumstances, certain parents, certain things out of your realm of control. How you deal with those challenges is the important, relevant question. --Jennifer M. Brown

author photo: Julian E. Barnes

Katherine Marsh: Fate and Free Will

And this is the central question for Jepp. While Jepp believes human beings make our own fates, Magdalene believes the stars determine our course. As the story progresses, they come to respect one another, and open up to the possibilities of the other's point of view. Because her father married for love, not station, Magdalene cannot take her father's name nor inherit his lands. Like Jepp, she knows what it means to have no true place in society.

And this is the central question for Jepp. While Jepp believes human beings make our own fates, Magdalene believes the stars determine our course. As the story progresses, they come to respect one another, and open up to the possibilities of the other's point of view. Because her father married for love, not station, Magdalene cannot take her father's name nor inherit his lands. Like Jepp, she knows what it means to have no true place in society. Katherine Marsh was born exactly as charted by an astrologer whom her mother, then 30, consulted back in the 1960s. The astrologer predicted that her mother would have a girl late in life, and that she'd be a Scorpio. Marsh struggled with the idea of fate but also believed she could make her own decisions. "That struggle was something I wanted to write about," said Marsh. "I did some research and discovered there was this time when science and astrology were one and the same." That time is the 16th-century setting for Jepp, Who Defied the Stars.

Katherine Marsh was born exactly as charted by an astrologer whom her mother, then 30, consulted back in the 1960s. The astrologer predicted that her mother would have a girl late in life, and that she'd be a Scorpio. Marsh struggled with the idea of fate but also believed she could make her own decisions. "That struggle was something I wanted to write about," said Marsh. "I did some research and discovered there was this time when science and astrology were one and the same." That time is the 16th-century setting for Jepp, Who Defied the Stars. That also goes to the heart of the Renaissance, doesn't it?

That also goes to the heart of the Renaissance, doesn't it? Perhaps the best known Italian detective is Commissario Guido Brunetti, the thoughtful, socially conscious, gourmet creation of Donna Leon. He, his fiery wife Paola, their two bright children, and his phlegmatic assistant Inspector Vianello have now appeared in 21 books. Brunetti's love for his native Venice flavors every investigation he undertakes, including his latest excursion:

Perhaps the best known Italian detective is Commissario Guido Brunetti, the thoughtful, socially conscious, gourmet creation of Donna Leon. He, his fiery wife Paola, their two bright children, and his phlegmatic assistant Inspector Vianello have now appeared in 21 books. Brunetti's love for his native Venice flavors every investigation he undertakes, including his latest excursion:  At the other end of the country, Andrea Camilleri's Inspector Montalbano is fiercely proud of Sicily, in spite of its Mafia connections. In

At the other end of the country, Andrea Camilleri's Inspector Montalbano is fiercely proud of Sicily, in spite of its Mafia connections. In  The busy Italian capital shines in the Commissario Alec Blume series by Conor Fitzgerald. Originally from Seattle, Blume now works for the Roman police force, and is obstinately determined to catch killers, no matter the odds. In his latest adventure,

The busy Italian capital shines in the Commissario Alec Blume series by Conor Fitzgerald. Originally from Seattle, Blume now works for the Roman police force, and is obstinately determined to catch killers, no matter the odds. In his latest adventure,  Even Tuscany, portrayed as idyllic in countless movies and books, was once plagued by a vicious serial killer. Author Douglas Preston tells the true story of this person who terrorized the Tuscan countryside in the 1970s and 1980s in The Monster of Florence. The real Monster was never caught, but Preston's detailing of the case brings Tuscany disturbingly to life. --

Even Tuscany, portrayed as idyllic in countless movies and books, was once plagued by a vicious serial killer. Author Douglas Preston tells the true story of this person who terrorized the Tuscan countryside in the 1970s and 1980s in The Monster of Florence. The real Monster was never caught, but Preston's detailing of the case brings Tuscany disturbingly to life. -- Jim Heynen

Jim Heynen