_Jana_Kirn.jpg) |

| photo: Jana Kirn |

Gilbert Gaul has twice won the Pulitzer Prize and been shortlisted for the Pulitzer four other times. For more than 35 years, he was an investigative journalist for the Washington Post, the Philadelphia Inquirer and other newspapers. He has reported on nonprofit organizations, the business of college sports, homeland security, the black market for prescription drugs and problems in the Medicare program. He was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University and a Ferris Fellow at Princeton University. The author of three previous books of investigative reporting, Gaul's latest is Billion-Dollar Ball: A Journey Through the Big-Money Culture of College Football (Viking, August 25, 2015).

College football is a standalone business with money flowing in primarily from TV and stadium seating revenue. Does any of that money go to programs other than football?

The way the business model works is that all the money is plowed back into the athletic department, and most goes to the football operation because that's the driver for the bus. Many people are under the mistaken assumption that large chunks of money from these football empires go to academics or other parts of the schools, but very, very little does.

The athletic directors are pretty good businessmen--they've figured out a way to monetize every inch of their football stadiums and programs. And you see this extraordinary growth of college football over the last few decades in terms of the revenue. Their defense is that it's big, it's all this money, but we use it to pay for women's rowing, for women's soccer or men's baseball. There are all kinds of counterarguments as to why this is a bad idea, ranging from out-of-control spending to the negative impact on academics to the controversial idea of using football--not education--as your primary brand.

The profit margin for football programs is outstanding, but what's the cost of football being the tail that wags the dog?

That's a big issue that I became interested in: making football your primary brand--which is essentially what's happened at these hugely successful schools. The have-nots who want to be part of the elite will never get there--all the money goes to the elites. If you are the president of a school where football is the brand, what does that say about your school? You're seen through the prism of the team, not through the prism of an educational facility. That really sends a message.

A lot of people have become inured to this; we simply are so obsessed with sports as entertainment in this country that we don't think critically about these issues, and that allows them to perpetuate. People just shrug and say, what difference does it make? But it does make a difference. What is your university about? Take Penn State: you think "football." But they have probably the best undergraduate business program in the nation.

One point I try to stress is about the college presidents. They made a decision--I think they were encouraged some years ago by the Knight Commission--to make athletics self-funding. What I asked presidents is this: If you really think football is an important part of the educational process (which they will argue), then why don't you use university dollars to fund your football team? Why don't you pull all of the revenue you get from this standalone business and subject it to the same budgetary constraints that the rest of the school is under?

They are always tongue-tied with this question--they are embarrassed, but afraid to admit that and do anything about it because they know they'll have their heads cut off. So it's a fundamental contradiction.

Supposedly, being a student athlete means becoming a more well-rounded (and educated) person. That may be true at some smaller schools, like Haverford. But not at the University of Texas, say.

Supposedly, being a student athlete means becoming a more well-rounded (and educated) person. That may be true at some smaller schools, like Haverford. But not at the University of Texas, say.

The operation of a school like Texas or Oregon or Ohio State is so much more commercialized and professionalized. It's a totally different experience for the athletes going through it. I have a chapter on women's rowing in the book (my favorite chapter); if you look at Olympic sports, it's an intense experience, but these athletes in general are not a problem academically--they are serious students majoring in "real" subjects. You see much less of that with football, and part of that is the time commitment: it's so intense that the players don't have time to be real students. There's always an exception, but if you look at the larger numbers, you see clustering in subjects that are easier--less of a demand on time, like sociology. I had no idea so many football players wanted to be sociologists.

The other phenomenon is the academic support programs. There has been a lot written about scandals involving football players--like the massive cheating scandal at UNC--but what I was interested in was taking a macro look. These academic support programs cost millions of dollars a year--tutors, learning specialists, psychologists, plus very expensive buildings that are exclusively for the athletes. Look at the $42 million, lavish academic center at Oregon, funded by Phil Knight (Nike). Then look at the honors college, located in a 75-year-old structure: the heating system is broken, the elevator is broken, there's no interior staircase. You can't but ask yourself about the university's priorities here. Is it keeping football players eligible or is it encouraging the brightest students? Look at the scholarship comparison with the honors college--the kids get a few thousand dollars, if they're lucky, while a football scholarship is $40,000-$50,000 a year.

Even with all that support, the athletes are essentially working full time while going to school--academics can be a distraction from that job. At a time when we need to upgrade our colleges, produce more STEM graduates for instance, how can we justify football programs as they are currently run?

Well, I don't think you can justify it the way it exists now, on any number of levels, including the one you just mentioned. I also think that, under the tax code we have, the fact that we treat all this as though it is a charity is absurd. The only reason this situation exists is because you have a big and powerful football lobby and senators and Congressional members from football-mad states. Every time there is an attempt to change it, it's defeated. There is an 80% tax deduction for a mandatory payment to get premium stadium seating--that's just nuts. The IRS knows this; they knew it back in the mid-'80s and they tried to do something about it and got defeated by the football lobby. College presidents allow this to go on. They wring their hands year after year, and yet they either don't want to or are afraid to try to do real reforms because they know if they do, they'll lose their jobs. So the question is: Where is real reform going to come from? Congress doesn't want to deal with it, presidents don't want to deal with it, trustees don't want to deal with it.

Colleges with sub-par football teams still get a massive piece of the TV revenue pie; smaller schools will get into a division to get money (and PR exposure) for getting shellacked in games. What is the psychic cost of having a bad team performing on national TV--on the players, the coaches, the students?

The big schools load up in the beginning of the season with games against lower-tier schools or really bad division 1 teams. That "lesser" school will be guaranteed, say, $900,000. They lose 55-0, or whatever, and the elite school tops up its winning record, which helps later in the season to get to a bowl game, where they get yet more money. The weaker schools struggle financially. Some of these schools probably shouldn't be playing football. The University of Alabama Birmingham tried pulling out--the president got beaten up and now the football team is coming back.

What would happen if Congress changed the charity aspect of college ball?

It's a little tricky to answer because you could say the business model collapses if you tax the television revenue, or especially if you were to take away the deduction for all of the premium seating--what they call seat donations, which is an Orwellian term because there's no donation involved, it's a quid pro quo.

What some people have told me is that could happen, but the schools aren't dumb, they would find ways to increase their expenses so in effect they wouldn't end up paying any actual tax--they'd basically just net it out at zero.

But I have no illusions about this. Congress will not act. It's important to think about, because it really is an abuse of the concept of charity. But nobody wants to talk about it.

You believe a big threat to college football is the shortened attention span of young people.

I do think that's an issue. What you see now with students is a lot less interest in going to a game. They don't develop the same kind of loyalty that fans and students in the past have had. There have been troubles getting students at some schools to attend, and if they do go, they leave at halftime. This happened at Alabama last year. Nick Saban actually got angry and tongue-lashed the kids for not staying. Both humorous and sad. --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Gilbert Gaul: The Broken College Football System

Robin Talley's Lies We Tell Ourselves takes a fictional approach to the same issue, following two girls on opposite sides of the desegregation debate in a Virginia high school: Sarah Dunbar, one of the first black students to attend the previously all-white school; and Linda Hairston, the white daughter of the town's most vocal opponent to desegregation. Talley's account of Sarah's experiences entering the school is detailed and emotional, and the novel fully brings to life the very personal experiences of those students at the forefront of integration.

Robin Talley's Lies We Tell Ourselves takes a fictional approach to the same issue, following two girls on opposite sides of the desegregation debate in a Virginia high school: Sarah Dunbar, one of the first black students to attend the previously all-white school; and Linda Hairston, the white daughter of the town's most vocal opponent to desegregation. Talley's account of Sarah's experiences entering the school is detailed and emotional, and the novel fully brings to life the very personal experiences of those students at the forefront of integration.

_Jana_Kirn.jpg)

Supposedly, being a student athlete means becoming a more well-rounded (and educated) person. That may be true at some smaller schools, like Haverford. But not at the University of Texas, say.

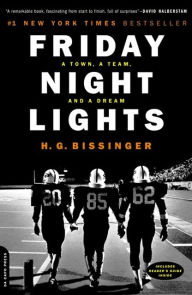

Supposedly, being a student athlete means becoming a more well-rounded (and educated) person. That may be true at some smaller schools, like Haverford. But not at the University of Texas, say.  After Addison-Wesley published H.G. "Buzz" Bissinger's nonfiction book Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream in 1990, the anger toward Bissinger in the city of Odessa, Tex., was so strong that the author had to cancel the Odessa portion of his tour. Ostensibly a chronicle of the 1988 season of the Permian Panthers high school football team, Friday Night Lights is also a social history and expose of an economically depressed and shockingly racially divided city of 90,000 in West Texas. Throughout the book, Bissinger focuses in particular on six players on that Permian Panthers team, including fullback Don Billingsley, quarterback Mike Winchell and running back James "Boobie" Miles, who is worshiped by Permian fans until he suffers a serious knee injury and is all but thrown away.

After Addison-Wesley published H.G. "Buzz" Bissinger's nonfiction book Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream in 1990, the anger toward Bissinger in the city of Odessa, Tex., was so strong that the author had to cancel the Odessa portion of his tour. Ostensibly a chronicle of the 1988 season of the Permian Panthers high school football team, Friday Night Lights is also a social history and expose of an economically depressed and shockingly racially divided city of 90,000 in West Texas. Throughout the book, Bissinger focuses in particular on six players on that Permian Panthers team, including fullback Don Billingsley, quarterback Mike Winchell and running back James "Boobie" Miles, who is worshiped by Permian fans until he suffers a serious knee injury and is all but thrown away.