_Mark_Hanauer.jpg) |

| photo: Mark Hanauer |

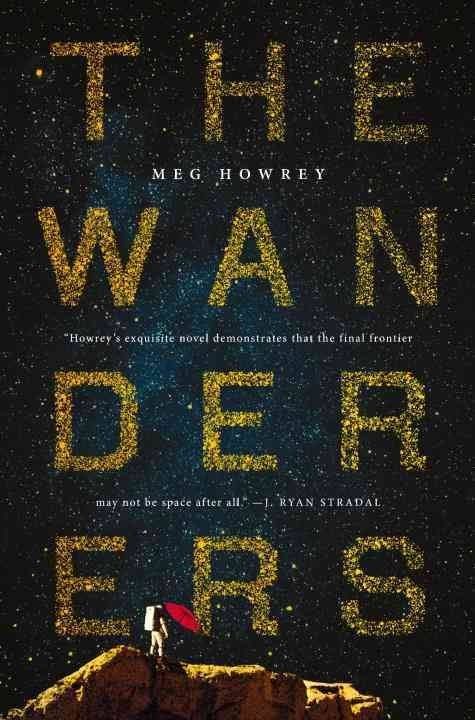

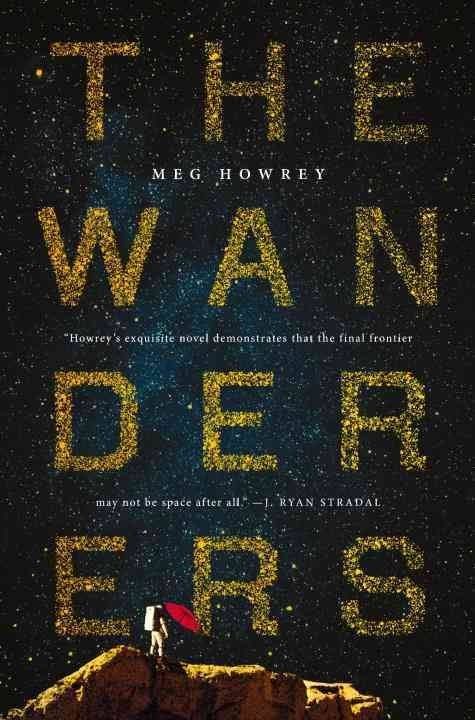

Meg Howrey is the author of the novels The Cranes Dance and Blind Sight. She is also coauthor, under the pen name Magnus Flyte, of City of Dark Magic and City of Lost Dreams. In her new novel, The Wanderers (just published by Putnam), Howrey sets up a simple premise: three astronauts are chosen to participate in a simulation of the first-ever mission to Mars. What unfolds, however, is anything but simple. As the plot progresses, each of the three embarks upon an internal voyage, learning what it means to be real in an age where the very definition begs reexamination.

What inspired you to write a story about astronauts? Are you interested in space exploration?

The idea came from a newspaper article I read several years ago, about a collaborative project between European and Russian space agencies. They put six volunteers into a capsule for 520 days, to simulate the length of a mission to Mars. It was, of course, meant to test the physical and psychological effects of a voyage like that.

I read that article and thought, "That would make a great novel!" Because space is other people, right? But I thought I couldn't write it because I didn't know anything about space exploration. In fact, I wanted to not write this novel. For about a year and a half, all I was doing was reading about space exploration. I did a ton of research, learning as much as I could. So this project was about four years in the making.

After all that research, how did you decide what information to include and leave out?

Well, you want to put everything in--because it's all so fascinating. The work that's being done in space exploration is amazing. I would write these long technical paragraphs and then delete them, or move them into another file. I had a lot of "nerd moments" where I just wanted to write about all these things I'd learned, but I was really trying to avoid that kind of info dump in the novel. So I'd write it all out and then move it. I also figured that this information is out there in the hands of gifted science writers, for people to discover if they want to. I cite a few really helpful books in the acknowledgments at the end of my book, if readers are interested in learning more.

The Wanderers is told from multiple perspectives: those of the three astronauts and several other characters, including their family members. How did you decide to write from multiple points of view?

I originally intended to tell the story from only my three main characters' perspectives. That seemed like a neat and tidy way to do it. But in an effort to better understand Helen, who was the first character I was developing, I decided to write a chapter from her daughter's perspective. I knew it would make the book messier to have those different points of view--it's always a risk. But I had to try it. And I decided to leave it in. Ultimately, it made sense, because this is a book about those who are left behind, as well as those who go. The astronauts are in the simulation of the journey to Mars, but all the characters are struggling with simulations--some of them of their own devising.

Can you talk about that idea of simulations? How did that allow you to explore the boundaries of what is real and not real, for the astronauts and their families?

Can you talk about that idea of simulations? How did that allow you to explore the boundaries of what is real and not real, for the astronauts and their families?

I was so interested in exploring that idea. The characters are all being asked to pretend something they've already experienced: the astronauts have all already been to space, and their family members have had to deal with that. And now this experience is not "real," but the feelings they're having about it are real.

The idea of simulations was always the spine of the book--much more so than space travel. It's about isolation and confinement and identity, and this idea of what is real. Of course, that got more complicated the farther I got into the book!

In a sense, of course, the novel itself is a simulation. You ask the reader to enter the novel and accept that what they're being told is real--which is one of the reasons we love to read, to enter into a story like that. So in this case, form and content were closely aligned.

We live in a world with a lot of simulations right now: smartphones, computers, virtual reality--in addition to these older forms of storytelling and simulation.

Yes, absolutely. So the idea of reality, and what is real and not real, felt very close to me as I was writing. It seems important that we try to figure this thing out: What are we looking at? What is real? And currently, in the news, we're seeing that, too, with the debates over what is true. So my characters are experiencing a reality, but they've also been given a set of circumstances and been asked to pretend they're real. I was interested in exploring that.

Your characters are also being observed constantly, which might have an effect on their reactions to their circumstances.

Yes. The more I read about space travel, the more I realized that most of an astronaut's work is not going to space--it's training: being observed and evaluated. And the people who really succeed there are people who value their performance over personal comfort. I was interested in how these three characters would grapple with that. They're able to put up good facades for their observers, but some things eventually start to unravel.

We all admire the heroism of people like astronauts, but they are, first, human beings. I think it's more interesting and satisfying to land a person on Mars, or another planet, rather than a robot. We're such a complicated, strange and fragile little species. There's a cosmic longing not to be alone in the universe, and to know why we're here, but there's also a longing to be better than we are. There's something more beautiful about a complicated, messy person landing on Mars than a perfect astronaut hero. I want a person to land on Mars and be moved and excited and fascinated and afraid. And I like to think that people such as my characters--people who are fully human--are the best people to send. This is a book about inner space, more than outer space.

That's true for your supporting characters as well.

Yes. I was interested in what it takes to be an astronaut, but also in what it takes to love one. It's a big ask! We all have ideas of what a mother or father or sibling or lover should be, and those are also simulations: they don't always match up with the reality. How useful are those simulations if those relationships are flawed or complicated? And what happens when we let go of our ideas about those categories? Helen might not be a good mother by some standards, but if she and her daughter--and by extension, we, the readers--let go of certain ideas about what it means to be a good mother, then she might be an amazing one.

Anything else you’d like readers to know about the book?

I'd like readers to come to the novel with an open mind. It straddles the worlds of fiction and science fiction, and I think there are often certain expectations about what a space story will look like: lots of adventure and excitement, or a "hard" sci-fi story with lots of technical information. This is a different take. I hope both fans of the sci-fi genre and those of fiction in general will find it interesting because it’s a human story. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

Meg Howrey: Exploring the Boundaries of Inner Space

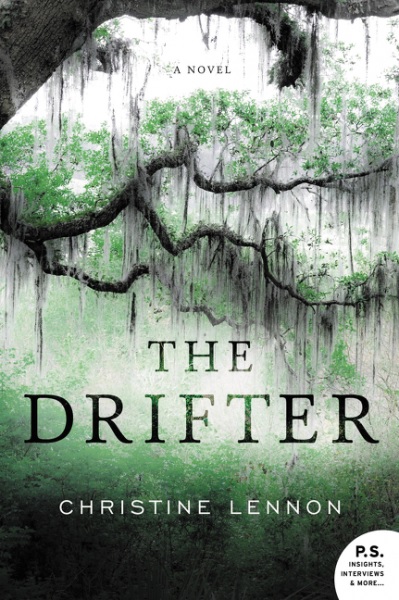

Before leaving New York City for the West Coast, Christine Lennon was an editor at W, Vogue and Harper's Bazaar. Her first novel, The Drifter (Morrow), is about a group of friends whose lives are changed forever by a violent event they experience in college. It's a love letter to the '90s, and a story about the complexities of friendships and the secrets that can ultimately destroy us.

Before leaving New York City for the West Coast, Christine Lennon was an editor at W, Vogue and Harper's Bazaar. Her first novel, The Drifter (Morrow), is about a group of friends whose lives are changed forever by a violent event they experience in college. It's a love letter to the '90s, and a story about the complexities of friendships and the secrets that can ultimately destroy us.  Book that changed your life:

Book that changed your life:

_Mark_Hanauer.jpg)

Can you talk about that idea of simulations? How did that allow you to explore the boundaries of what is real and not real, for the astronauts and their families?

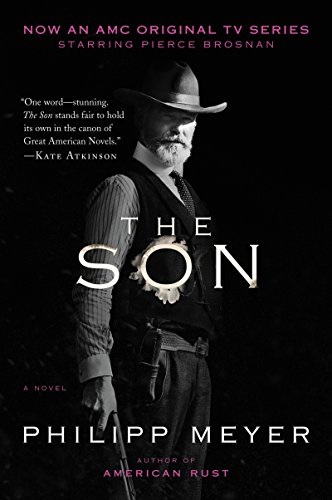

Can you talk about that idea of simulations? How did that allow you to explore the boundaries of what is real and not real, for the astronauts and their families? Philipp Meyer's second novel,

Philipp Meyer's second novel,