|

| photo: Sveta Mishima |

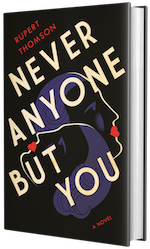

Rupert Thomson is the author of several novels, including The Insult, selected by David Bowie as one of 100 Must-Read Books of All Time; Death of a Murderer, shortlisted for the 2008 Costa Novel; and Katherine Carlyle. His latest novel, Never Anyone but You, tells the story of the real-life love affair between Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. Thomson lives in London.

Never Anyone but You is based on a true story. How did you first come across Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore?

I found a photo of Claude Cahun in a magazine. She had shaved eyebrows, a shaved head, and she was wearing a black dress. Her head was kind of turned away. She just looked really bizarre. And I thought, "Who is that?"

There were a few biographical details in the article, and they were so intriguing. It was such an extraordinary story, and one I hadn't heard before. Never Anyone but You didn't start as a book quite then, but it lodged in my head, as these ideas often do.

The book is rich with historical detail across both women's lives and spanning several decades of the 20th century. How did you conduct your research?

I take a kind of peculiar attitude to research. I usually just start with my intuition. I wrote one or two drafts of the novel without knowing much at all. I do that to understand the psychological underpinnings of the characters. Background, structure, pace--all those things can come later, as far as I'm concerned. What I was really trying to get at is the relationship between Marcel and Claude.

This is a good thing and a bad thing. It's good because I nearly always discover valuable things that I wouldn't have discovered if I did all the research and at the end painstakingly constructed a book out of all the facts. It's bad because I make all kinds of mistakes. I write things that couldn't possibly have happened. So later on, I have a fair amount of problems.

I did go to Jersey twice, interviewed a bunch of people, and must have read over 100 books. I read and read and read, everything I could lay my hands on. But there does come a point when you realize you know what you need to know, and you have to go ahead with the writing.

I also tell this story from Marcel's voice. There are things she wouldn't have known in her life, or things she wouldn't have found important. The novel is her looking back on 40 years with an extraordinary and complicated woman. So all the research had to be run through the lens of Marcel's mentality. And that became a way of filtering what I was reading. That made it much easier to know what I was going to use and what I wasn't going to use.

You mentioned this approach caused some problems, though?

After I'd been working on the book for over a year, I tracked down François Leperlier, who wrote the main biography of Claude.

There was a point in August 2015 when we met in person and had drinks together and dinner, and I asked to be in touch with him via e-mail. He was so unbelievably patient and useful. I would have tiny questions like, "When the two women lived on Jersey, did they have a car?" and then I'd have huge questions like, "What kind of Marxist was Calhoun? What kind of Marxism did they believe in?"

We went back and forth on lots of questions, and then, a year later, I went and spent three days with him. That actually almost undermined the book completely. I have this opening scene, for example, that takes place when the Germans are about to occupy Jersey, and Marcel is swimming in the sea, and feels the bombs falling miles away. François stopped me and said, "That's impossible. There's no evidence that Marcel was in the sea when that happened. Claude wrote about that moment and never mentioned anything about it." But as far as I was concerned, there was nothing Claude wrote that says Marcel wasn't in the sea, either.

We had a kind of clash between the academic nonfiction writer and the fiction writer, who works with the imagination. It was a really interesting few days, because he'd keep finding things with no evidence to prove it did happen, while I felt there was no evidence to say it didn't.

I have a theory about real facts and imagined facts. And the imagined facts take precedence even though I'm writing about real people. What fascinated me most about their story is what happened behind closed doors. Those moments that no historian could write, because they can only write things based on evidence. But the whole point of fiction is to go beyond that. So, for me, if something felt psychologically appropriate, I'd go ahead with it.

Early in her relationship with Claude, Marcel says, "It was the life I was living that unnerved me. The path I had chosen was the one that I could not imagine."

That line looks so simple when you first read it, but it's actually quite a complicated idea. I believe mystery comes from clarity, rather than the other way around.

Marcel had, at one point, imagined a fairly conventional life for herself. Claude throws all of that completely up into the air. The idea of having a lover who is a woman at that time and that place was really unthinkable. I believe Claude's effect on Marcel was rather seismic. She changed Marcel completely.

Really, the book is a love story. It's one woman talking about the life she spent with another woman who is just extraordinarily complicated and complex and vulnerable. It is an exploration of what is it like to love someone so impossible. --Kerry McHugh

A Short Guide to a Happy Life (Random House, $15) and Being Perfect (Random House, $15) are a pair of small books based on commencement addresses given by acclaimed author Anna Quindlen at Barnard, her alma mater. They both provide inspiring advice, accompanied by beautiful photographs, on getting the most out of every day and living your best life, with a focus on happiness in the first book and avoiding the trap of perfectionism in the second.

A Short Guide to a Happy Life (Random House, $15) and Being Perfect (Random House, $15) are a pair of small books based on commencement addresses given by acclaimed author Anna Quindlen at Barnard, her alma mater. They both provide inspiring advice, accompanied by beautiful photographs, on getting the most out of every day and living your best life, with a focus on happiness in the first book and avoiding the trap of perfectionism in the second. The perfect gift for high school grads moving on to college is The Naked Roommate (and 107 Other Issues You Might Run into in College) (Sourcebooks, $14.99) by Harlen Cohen, which combines practical advice on problems they might be embarrassed to ask about with a great sense of humor, plus stories from actual college students.

The perfect gift for high school grads moving on to college is The Naked Roommate (and 107 Other Issues You Might Run into in College) (Sourcebooks, $14.99) by Harlen Cohen, which combines practical advice on problems they might be embarrassed to ask about with a great sense of humor, plus stories from actual college students. For my son's college graduation, I searched for the perfect book to help him begin his adult life, and I found it in Adulting 101: #Wisdom4Life (Broadstreet, $14.99) by Josh Burnette and Pete Hardesty. There are lots of books out there on finding a job or being successful at work or learning how to manage your finances, but this practical guide for those embarking on adult life includes all that--and much more. --Suzan L. Jackson, freelance writer and blogger at Book by Book

For my son's college graduation, I searched for the perfect book to help him begin his adult life, and I found it in Adulting 101: #Wisdom4Life (Broadstreet, $14.99) by Josh Burnette and Pete Hardesty. There are lots of books out there on finding a job or being successful at work or learning how to manage your finances, but this practical guide for those embarking on adult life includes all that--and much more. --Suzan L. Jackson, freelance writer and blogger at Book by Book

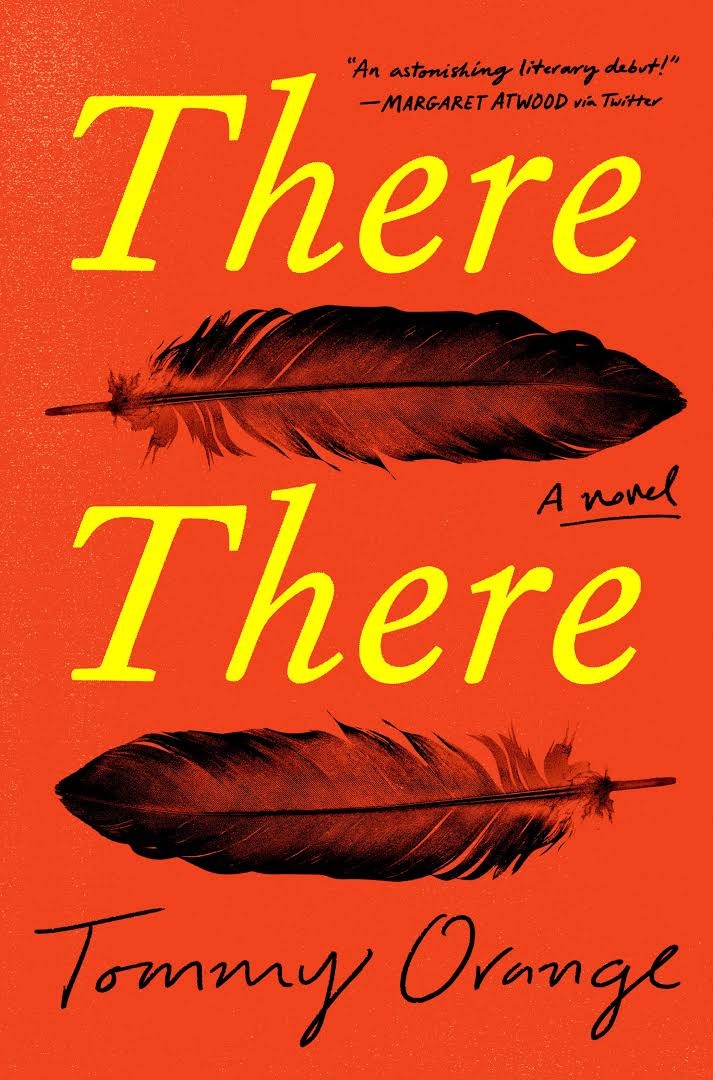

In the U.S. as a whole, we like to think of Indians historically and romantically; if we think of urban Natives, we think of homelessness and alcoholism. You write, "We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere." You are pushing against stereotypes.

In the U.S. as a whole, we like to think of Indians historically and romantically; if we think of urban Natives, we think of homelessness and alcoholism. You write, "We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere." You are pushing against stereotypes.