|

| photo: B Dalcher |

Christina Dalcher earned her doctorate in theoretical linguistics from Georgetown University. She specializes in the phonetics of sound change in Italian and British dialects, and has taught at several universities. Her short stories and flash fiction have appeared in more than 100 journals worldwide. She lives in Norfolk, Va., with her husband. Vox

(Berkley, $26), reviewed below, is her first novel.

Vox has been compared with Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale. How do you feel about that?

I think many dystopias can be compared with another because dystopian literature is almost always based on the common person being oppressed by a totalitarian system. It's certainly a compliment to see Vox being compared with other books, both classic and contemporary. Of course, all books are different. I wanted to explore how we rely on language without realizing it. We take it for granted.

I read Vox as a cautionary response to current events--particularly the threats to women's rights in the United States and elsewhere. Was that your intention?

Yes and no. Most of Vox is me asking "what if we returned to that culture?" That's exactly what we did after women won the right to vote and in the 1950s after women joined the workforce. Vox certainly can be read as a cautionary tale. While Jean's story is set in the near future, the idea of speaking out while you can is timeless.

What was your inspiration?

I kept thinking about a world in which all humans suffered from fluent aphasia--one type of language loss resulting from trauma to the brain, making people completely unable to communicate and perhaps robbed of the ability to think. Language is really the single element that defines us as human, separating us from the rest of the animal kingdom. It was terrifying to explore.

You wrote Vox in two months. Tell us about that process.

You wrote Vox in two months. Tell us about that process.

It originated as a short story, one that my readers wanted to see expanded. Also, I work off a bare-bones outline of about a dozen sentences. If I want to know what's going to happen next, I need to write it. I'm part of the audience, which is exciting.

You write flash fiction (only a few hundred words or fewer), which has the perception of being "easy" to write. What has your experience been? And what advice can you offer to others who want to explore this genre?

Flash has always come easily to me, probably because of my academic background where abstracts for journal articles and conference presentations require only a few hundred words. For newcomers to the form, I'd suggest reading stories in flash fiction journals and lit mags. When I'm not tweeting about Vox, I'm almost always tweeting about flash, usually a recent story by someone in my writing community. Once you know where to look, you'll find flash fiction everywhere! Then just write your heart out.

How does the process of novel writing compare to your academic writing?

I'm so happy you asked me this! Vox is dedicated to the memory of Charlie Jones, who was my first linguistics professor and a brilliant syntactician. He was also the most parsimonious sonofabitch I'd ever met. This man's idea of an academic paper was two pages that were condensed so tightly, I think the sheets they were written on screamed in protest. But Charlie taught me how to be lean and how to write something complex using the fewest words possible. When it came time to think about a 350-page doctoral dissertation, I asked Charlie how in the world I would do it. His response? "One chapter at a time, man." And he was right.

Can you share a bit about what you are working on now?

I finished the first draft of book two a few months ago. It's not a continuation of Jean's story, although I haven't ruled out a follow-up. Instead, I went back to the early 20th century when we had a strong eugenics movement in the United States. I decided to use that as the basis for another near-future dystopia in which intelligence testing has run amok.

In 25 years, what will readers be saying about Vox?

I hope people will still read the book, because of its timeless message.

Vox could have taken place at any point in our history, because at its core, Jean's story is about a power exchange: the state gains more control at the expense of individual freedom. We've seen this happen before. We're seeing it happen now. And I'm sure we'll see it happen again. When it does, maybe people will read

Vox or go to the polls or find a way to tip the balance of power back in their favor. --

Melissa Firman

Christina Dalcher: When Silence Speaks Volumes

In Mary Doria Russell's debut novel, The Sparrow, when humankind hears distant noises from outer space, the Jesuit order sends a secret mission to a world known as Rakhat to make contact with aliens. The story is not a happy one, but it is a fascinating imagination of what could happen if (when?) humans encounter alien life for the first time.

In Mary Doria Russell's debut novel, The Sparrow, when humankind hears distant noises from outer space, the Jesuit order sends a secret mission to a world known as Rakhat to make contact with aliens. The story is not a happy one, but it is a fascinating imagination of what could happen if (when?) humans encounter alien life for the first time. Andy Weir was similarly taken with the concept of space travel, though his debut, The Martian, took a more literal approach. Weir stated in interviews that he intended his novel to be as scientifically accurate as possible; though much of the technology used by protagonist Mark Watney in his stranded-on-Mars mission is prohibitively expensive, we're told it could theoretically exist.

Andy Weir was similarly taken with the concept of space travel, though his debut, The Martian, took a more literal approach. Weir stated in interviews that he intended his novel to be as scientifically accurate as possible; though much of the technology used by protagonist Mark Watney in his stranded-on-Mars mission is prohibitively expensive, we're told it could theoretically exist. Nonfiction writers promise even more science, astronomy and math: Margot Lee Shetterly's Hidden Figures reveals the oft-overlooked history of a team of African American women who were mathematicians at NASA in the 1960s and whose calculations were key to the space program. Mary Roach's Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void explores the very strange, very necessary science behind keeping astronauts alive in environments not designed to do so. Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil deGrasse Tyson promises an (hyper-condensed) answer to questions about the universe.

Nonfiction writers promise even more science, astronomy and math: Margot Lee Shetterly's Hidden Figures reveals the oft-overlooked history of a team of African American women who were mathematicians at NASA in the 1960s and whose calculations were key to the space program. Mary Roach's Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void explores the very strange, very necessary science behind keeping astronauts alive in environments not designed to do so. Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil deGrasse Tyson promises an (hyper-condensed) answer to questions about the universe.

You wrote Vox in two months. Tell us about that process.

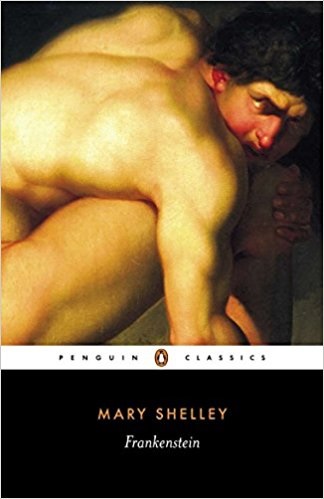

You wrote Vox in two months. Tell us about that process. In 1818, when Mary Shelley was just 20 years old, the first edition of her novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published anonymously in London. By the time Shelley's name appeared on a second edition in 1823, her work had polarized critics while achieving popular success. In a hint of things to come, Frankenstein was already being adapted into derivative works even during Shelley's lifetime, including a stage play she saw with her father, William Godwin, in 1823. In the 200 years since, Shelley's reanimated creature has become its own pop-culture monster, as much a product of film and TV depictions as the original novel.

In 1818, when Mary Shelley was just 20 years old, the first edition of her novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published anonymously in London. By the time Shelley's name appeared on a second edition in 1823, her work had polarized critics while achieving popular success. In a hint of things to come, Frankenstein was already being adapted into derivative works even during Shelley's lifetime, including a stage play she saw with her father, William Godwin, in 1823. In the 200 years since, Shelley's reanimated creature has become its own pop-culture monster, as much a product of film and TV depictions as the original novel.