Friday, February 9, 2024

This week, we review the "stunning work of enduring literary beauty" that is poet Kaveh Akbar's first novel, Martyr!, as well as the "world of magic" within the "vivid and poetic" City of Stardust. We also take a sobering look at one epidemic of work-related cancer in "the harrowing debut from journalist Jim Morris," The Cancer Factory. And for younger readers, we highlight Kengo Kurimoto's "visual storytelling perfection" in the graphic novel Wildful.

In The Writer's Life, novelist Francis Spufford elaborates on how he went about reimagining American history for his genre-defying detective novel Cahokia Jazz.

Martyr!

by Kaveh Akbar

In Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar (Pilgrim Bell), destinies collide in a most spectacular fashion when an Iranian-American poet from Indiana meets a dying artist. Akbar's first work of fiction is an electrifying drama swirling with themes of sobriety, sexuality, and the meaning of art as the story travels from Tehran to Indiana and New York.

Martyr!, set in the recent past and alive with crafty, energetic prose, follows Cyrus Shams, a former raging alcoholic who, approaching 30 and feeling directionless, decides it's high time he created something big and meaningful through his writing. Until now, his existence has been defined by the death of his mother in 1988, during his infancy, when the U.S. Navy accidentally shot down the commercial airliner she was traveling on from Tehran to Dubai. The meaninglessness of her death haunts him and belatedly inspires him to make his own life--and death--matter.

Cyrus is determined to write a book about real-life martyrs, or "earth martyrs," and travels to New York to interview the mysterious painter Orkideh. Orkideh has terminal cancer and is spending her final days at the Brooklyn Museum in an exhibit called "Death-Speak," inviting museumgoers to spend time with her and, essentially, watch her die. Talking about death with the artist transforms and unsettles Cyrus, setting the stage for a radical moral reckoning for both parties.

Like the delicate shards that make up Iranian mirror art, Martyr! pieces together multiple narratives to deliver a stunning work of enduring literary beauty. --Shahina Piyarali

Discover: An Iranian-American poet has a fateful encounter with a mysterious, terminally ill artist in this electrifying drama set in Tehran, Indiana, and New York.

Cahokia Jazz

by Francis Spufford

British author Francis Spufford (Red Plenty; Golden Hill) brilliantly transforms the American landscape with immersive storytelling in Cahokia Jazz, an alternate history spotlighting an Indigenous Midwest metropolis in 1922 fighting for its continued existence.

Indigenous Cahokia policeman Joe Barrow and his white partner, Phineas Drummond, are summoned to investigate a mutilated corpse--a white man--dramatically perched atop the pyramid skylight of the city's Land Trust building. While Barrow is drawn to the "real... elaborate" details of the gruesome murder, Drummond--Barrow's senior on the job by six months--recommends a more direct approach: "Better see who it is. The why's usually in the who." The media is ready to call it "a human sacrifice--in a city founded by Aztec royalty--and still ruled by Aztec royalty," but Barrow knows easy assumptions will only mask the truth. He has a week to catch the killer to keep the fragmented community's fragile peace, requiring a fine balance: delicate negotiations with the royalty, capitalist bosses, jazz sessions, and both kinds of clans--the familial and those hooded in white.

Spufford, who began his lauded career writing nonfiction, expertly infuses that talent into his imaginative world: Cahokia as ancient history and physical geography is real. Spufford's remarkable version here could exist, which he clarifies in his thoroughly convincing author's note. He assuredly populates this mesmerizing might-have-been setting with a notable cast, diverse in ethnicities, backgrounds, and beliefs. The occasional real person--cultural anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, for example--underscores Cahokia's aspirational reality. To read is to believe--and marvel. --Terry Hong

Discover: Francis Spufford's immersive Cahokia Jazz, set in a majority Indigenous metropolis in the American Midwest in 1922, is a mesmerizing amalgamation of imagination and could-have-been history.

The Road from Belhaven

by Margot Livesey

In The Road from Belhaven, Margot Livesey (The Boy in the Field; Mercury) eloquently traces the fictional life of Lizzie Craig, a girl from eastern Scotland in the late 1880s. After her parents die when she's a year old, Lizzie is raised by her loving, hardscrabble grandparents at Belhaven Farm--located inland, in the part of Scotland called "the Kingdom of Fife." Lizzie is just a toddler when she starts to have premonitions--secret visions she calls "pictures" that reveal future events that often confuse and frighten her. Sometimes these intuitions involve "ordinary things: her grandmother choosing which hen to kill; a cow stuck in the mud by the river." But other times, they prophesize harrowing actions and accidents over which she has no control. Or does she?

Lizzie is a lonely, responsible child when she learns that she has an older sister, Kate, who was sent to live with her paternal grandparents after their parents died. Circumstances change so that 16-year-old Kate now comes to live at Belhaven. The sisters, disparate in personality, struggle to adjust to one another, although in time they find ways to bond. But when she falls in love as a teenager, Lizzie chases her love interest to Glasgow, where her life takes heart-wrenching twists and turns. Is there any way Lizzie can harness her powers of perception in order to change the course of her own life and destiny?

Compassionately drawn and emotionally charged, Margot Livesey's novel maps the tenderest places of the human heart and soul and once again displays her indelible grasp on the human condition. --Kathleen Gerard, blogger at Reading Between the Lines

Discover: Margot Livesey draws a poignant, beautiful portrait of the romantic twists and turns that define the life of a perceptively sensitive Scottish woman in the 19th century.

Diva

by Daisy Goodwin

Diva by Daisy Goodwin (Victoria; The Fortune Hunter; The American Heiress) is a dazzling fictional retelling of the life of famous opera singer Maria Callas. Emerging from a humble background in Nazi-occupied Greece, Maria had an exceptional voice, which her mother discovered and used as a form of currency to fund their survival. Maria, exploited from a young age, had to get used to the steep price of her gift: family, friends, and even lovers who only saw her as "Callas," the most celebrated opera singer of all time, instead of as Maria.

By the time her career pushes her into leading roles at the greatest opera houses in the world, Maria's talent, work ethic, and self-worth are a testimony to female success. "Hard work, plenty of it," Maria notes as the secret to her success. "And high standards. I don't let anything obstruct my pursuit of excellence." Her dedication to her voice and career creates a force to be reckoned with in the opera world, but managers, journalists, and audiences label her a "diva."

Riddled with intriguing gossip and salacious rumors, Goodwin's contemplative narrative explores a fierce yet fragile female character. Maria's brash exterior slowly fades to reveal an increasingly complicated woman who is equally entertaining and endearing. Maria falls helplessly into a scandalous love affair full of delicious passion that puts into question what is most important: a career or true love. Diva sparkles with glamour, glimmers with hope, and is emblazoned with female empowerment. --Clara Newton, freelance reviewer

Discover: Daisy Goodwin's dazzling retelling of the life of opera singer Maria Callas is an exceptional story of ambition, love, and scandal.

Owning Up: New Fiction

by George Pelecanos

In one of the four boffo novellas that constitute Owning Up: New Fiction by crime novelist George Pelecanos (The Cut; The Double), a character recalls a film-critic friend's definition of film noir: "Nothing is going to be all right, ever." This may be true for many of Pelecanos's characters, but damned if they aren't at least trying to achieve more than the often precious little expected of them.

In one novella, a white convict is inspired to pursue acting by a Black convict he meets at a Washington, D.C., jail's book club. In another story, a successful author of books on police corruption fears that his work puts a target on his troubled son's back. A story beginning in the early 1980s finds a previously aimless woman trying to write a historical novel about a real-life D.C. theater tragedy. And in the title story, a Black man has a destiny-altering influence on a morally unformed white teenager who works with him at an appliance store.

Pelecanos's novellas are marvels of economy and compression while also managing to be cerebral and intricate. He wears his politics more visibly than did the old noir writers he clearly admires: his stories touch on racism, xenophobia, and other social impediments to getting ahead. Another occasional obstacle: the sort of hedonistic attitude that one character sums up as "We're all going to die, so what's the point of working?" Cruelly, it's the characters in Owning Up who resist moral laxity that have the bumpiest rides of all. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: These novellas, about people trying to achieve more than the often precious little expected of them, are marvels of economy and compression while also managing to be cerebral and intricate.

Hard by a Great Forest

by Leo Vardiashvili

The classic hero's quest takes traumatic and dark twists and turns in Leo Vardiashvili's lushly haunted debut novel set in post-Soviet Georgia. The hero of Hard by a Great Forest is Saba, a Georgian refugee who, as a child, flees the civil war with his father, Irakli, and his brother, Sandro. Scraping by in England, they're unable to send for their mother, Eka. She dies without seeing them again, as does most of the left-behind family.

Now, years later, after many false starts, Irakli sets off for Georgia--and then disappears. Sandro soon disappears, too, leaving cryptic notes for Saba, now a drifting 20-something, to follow. He travels to Georgia and immediately meets Nodar, a refugee from war-torn Ossetia, who becomes Saba's driver, landlord, and quasi-fixer. The two roam across vibrant, surreal Tbilisi following Sandro's breadcrumb trail of clues. The search--never leisurely--soon turns into a chase that leaves the boundaries of the capital city, amping up the already taut atmosphere. Along the way, Saba's visited by the voices and memories of those he lost, including a beloved neighbor, a grandmother, an uncle, and, most achingly, his mother. For years he's "avoided direct thoughts of Eka, the way your eyes might swerve the sharp light of the low winter sun." But now, faced with what he's left behind, Saba is forced to reckon with long-silenced emotions and yearnings.

Fans of Téa Obreht's The Tiger's Wife will feel right at home reading Vardiashvili's novel. Beyond their ravaged settings and many characters, they both feature escaped zoo animals wandering city streets, a penchant for twining folklore with storylines, and impressively evocative atmospheres. --Nina Semczuk, writer, editor, and illustrator

Discover: Hard by a Great Forest weaves mystery, adventure, folklore, and traumatic family history into a mesmerizing tapestry impossible to look away from.

The Wharton Plot

by Mariah Fredericks

Mariah Fredericks's The Wharton Plot, an atmospheric murder mystery featuring the renowned author Edith Wharton as its beguiling protagonist, is set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing New York City in 1911. With cameos by Henry James and mystery writer Mary Roberts Rinehart, and the sudden death of a famous author as its central plot, Fredericks's sixth historical novel is a suspenseful treat with an impressive literary pedigree.

The story opens with Wharton arriving in New York for a consultation with her husband Teddy's doctor. Five years have passed since the raging success of her novel, The House of Mirth. At 50 years of age, she finds herself at a difficult crossroad in her life, with a collapsing marriage, a mentally unstable spouse, and a former lover whose discretion she can't count on. When a fellow writer she met at her hotel is fatally shot in broad daylight, Wharton can't help but throw herself into solving the crime. The investigation brings her into contact with the victim's mistress and a host of potential suspects, leading to a climactic confrontation when the actual murderer lures her to a fateful meeting in Gramercy Park.

Wharton, as bought to life by Fredericks (Death of a Showman; The Lindbergh Nanny), is her formidable self, gloriously armored in pearls, lace, and furs. The Wharton Plot expertly blends historical facts with clever fictional details to create an absorbing drama in the vein of Wharton's own splendid novels, complete with that famed author's dry wit, social observations, and stylistic flourishes. --Shahina Piyarali

Discover: The famed author Edith Wharton investigates the murder of a fellow writer in this atmospheric mystery novel set in New York in the early 20th century.

Set for Life

by Andrew Ewell

The campus novel meets lad lit in Andrew Ewell's Set for Life, an exceedingly smooth debut narrated by an unpublished writer in crisis--actually, crises. And they're of his own making.

As the novel opens, the narrator, who goes unnamed, has flown back to New York after spending three months in France, where he had a writing fellowship for which he did little writing. Before returning to his successful-novelist wife upstate, where they both teach at a liberal arts college, he visits a couple in Brooklyn--friends since graduate school. The narrator sleeps with the woman--his best friend's wife, who is also his wife's best friend. Of apparent lesser concern to him than the fate of his marriage: in order to satisfy the conditions for tenure, he must produce "a single-author volume of no less than two hundred pages under contract with a national press by the time of promotion. So why couldn't I do it?" Readers will have an inkling. Likewise, the narrator's wife has him sussed: her agent calls her work in progress a "terrific spoof of white male angst."

Although Ewell isn't fully committed to satire, Set for Life keeps up a terrific running gag about the genre-fication of literary fiction and the increasingly commercially minded publishing world. As unsympathetic as the narrator can be, what will keep readers turning pages is the brute authenticity of his voice, which makes the novel go down as easy as the alcohol he guzzles without compunction or conscience. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: The campus novel meets lad lit in this exceedingly smooth debut revolving around a writer who's keen to publish a book but is doing little to bring this about.

Mystery & Thriller

Only If You're Lucky

by Stacy Willingham

The need to belong and to be a part of something--a club, a family, a friendship--is a strong desire, certainly for college student Margot in Only If You're Lucky, the intense third novel from Stacy Willingham (All the Dangerous Things).

Margot planned to room with her best friend, Eliza, at South Carolina's Rutledge College, which would allow them to deepen their bond. But just a few weeks after high school graduation, Eliza mysteriously dies. Margot spends a lonely freshman year rooming with a nice, but dull, roommate, until popular Lucy suddenly invites Margot to share an historic off-campus house with her and two other friends. Lucy appears to be the campus It Girl--poised, confident, a bit intimidating, dangerous. But her true nature is reflected in the unkempt house that desperately needs repairs, debris piling up. Margot willingly succumbs to Lucy's manipulation, becoming less inhibited and putting aside her grief over Eliza. But when Lucy disappears following the murder of Levi Butler, a pledge to the fraternity next door who was also Eliza's boyfriend and the last person to see her alive, Margot must face a horrible possibility--that Lucy may be a killer.

The friends' dynamic, especially what Lucy is willing to do for each of her housemates, imbues the plot with tension. Only If You're Lucky delivers an outstanding study of Margot, whose desperate craving for friendship is potent. It's understandable how she falls under Lucy's spell, whose "eyes seem to pierce you so deep, leaving behind microscopic little puncture wounds." Each character's secrets are slowly doled out for added suspense. --Oline H. Cogdill, freelance reviewer

Discover: A college student falls under the spell of a popular young woman with a dangerous streak in this suspenseful, character-driven thriller.

The Devil's Daughter

by Gordon Greisman

Private investigator Jack Coffey's memories become a mix of pride for some of his actions and regrets for others in The Devil's Daughter, screenwriter Gordon Greisman's highly entertaining fiction debut. Now in his 90s, with his eyesight and hearing waning, Jack says that "the past has a way of collapsing in on itself."

The Devil's Daughter quickly moves back to the pivotal year 1957, when Jack was involved in a career-changing case. Jack's friend Monsignor Richie Costello delivers a message from the archbishop of New York, for whom he is executive secretary: help wealthy church benefactor Louis Garrett find his 16-year-old daughter, Lucy. The powerful Garrett offers Jack a $10,000 retainer, and another $10 grand as a bonus, to bring Lucy home safely. Garrett paints his only child as "lovely," but admits "Lucy's a real handful," who may have been corrupted by her older, womanizing boyfriend, Rex Halsey, whom Garrett paid to leave the city.

Jack's investigation reveals a Lucy who is even more a wild child, and who may be involved with criminals and a series of murders. That's not far from who her father is: Garrett's façade of a well-respected businessman covers his Mafia activities. Jack wonders if Garrett wants Lucy found to protect her--or because she knows too much about her father's real businesses. Greisman adds the prerequisite dirty cops, vicious thugs, and Garrett's personal henchmen.

Greisman skillfully emulates vintage private-eye novels, delving into noir territory while also offering a hopeful future for Jack. --Oline H. Cogdill, freelance reviewer

Discover: A private investigator reflects on his search for a wealthy businessman's missing 16-year-old daughter, a career-defining case for him in 1957.

Twenty-Seven Minutes

by Ashley Tate

A car crash takes the life of a promising student in a small town. The community is ripped apart when they learn the two survivors waited before calling for help in Twenty-Seven Minutes, a hypnotic debut mystery by Ashley Tate.

Becca and siblings Phoebe and Grant were on their way home from a party. Grant swerved to avoid something in the road and crashed through a guardrail. Phoebe gets the worst of it: she's thrown from the vehicle upon impact. Twenty-seven minutes pass before the other two call for help. Neither Becca nor Grant can explain why they waited. The cops know Phoebe died because of the inaction of the other two, but they don't fully investigate.

Ten years pass. The town has tried to move on from the tragedy, despite the unspoken grudges and rumors that still linger among the locals. Then Grant's mother decides to hold a memorial for her beloved daughter. Attention-seeking Becca decides she's done covering for ungrateful Grant, who is haunted by Phoebe. Out of nowhere, another teenager--someone who disappeared the same night as the crash that took Phoebe's life--appears in town, threatening to tell everyone what really happened during those missing 27 minutes.

Tate so perfectly captures the dynamics of small-town life that it is hard to believe that she grew up in downtown Toronto. She presents all the heartache and disappointment of dashed hopes and unfulfilled dreams in this story of how multiple lives can be ruined in a manner of minutes. --Paul Dinh-McCrillis, freelance reviewer

Discover: In this nail-biting mystery, insistent ghosts force a small town to face the hard truth behind a fatal car crash.

Science Fiction & Fantasy

The City of Stardust

by Georgia Summers

In Georgia Summers's debut novel, The City of Stardust, Violet Everly is the kind of fantasy protagonist who lives up to genre standards while also managing to push the boundaries. She captivates readers with her yearning and charms them with her wildness--and occasional blundering.

The story sees Violet mature: "Much against her wishes, Violet grows up, rocketing from a short, half-feral child to a taller, half-feral teenager." She begins with many of the beloved fantasy foundations: a bookish, dreamy girl whose mother has disappeared; a family curse; and a magical world of scholars just out of her reach. But as she seeks answers to why her family loses a member once every generation, the tropes in play evolve into thoughtful complexity. Mothers are often an afterthought in fairy tales, but Summers makes her absence a centerpiece in a way that explores the tradition of mothers being quickly nudged out of the way. She gives Violet's mother depth even in absentia, sketching a portrait of a talented and headstrong woman who made her own way through life.

The world of magic is a mix of fairy tales and the intellectual, reminiscent of His Dark Materials--the kind of world readers can disappear into and somehow find that they've read into the early hours of the morning. The writing is gorgeous, with vivid and poetic descriptions, beautiful settings, and the immediacy that present tense brings.

The City of Stardust is a transporting fairy tale that transcends the genre with a surprising, contemplative ending that reconsiders the tropes with which it began. --Carol Caley, writer

Discover: This debut novel is a transporting fairy tale that transcends the genre while still delivering the long-beloved standbys of fantasy.

Romance

Canadian Boyfriend

by Jenny Holiday

Jenny Holiday (Duke, Actually; Mermaid Inn) presents a sweet, touching love story in Canadian Boyfriend. Years ago, teenager Aurora Evans met a cute Canadian hockey player at the Mall of America and turned him into her fake, long-distance boyfriend. He helped her through sticky social situations for years. In fact, Mike the hockey player even became the person Aurora addressed all her diary entries to. Now adult Aurora is back in Minnesota, teaching dance to children, and struggling with the trauma from her years in professional ballet in New York: an eating disorder and panic attacks.

Olivia, one of Aurora's students, recently lost her mom in a car accident, so Aurora starts helping her dad, Mike Martin, with getting Olivia to and from lessons. And when Aurora's lease is up, Mike asks her to move into their basement and act as Olivia's nanny and chauffeur when he's on the road. After all, he's gone a lot: he's a professional hockey player and also, to Aurora's shock, her fake Canadian boyfriend. Can Aurora separate her imaginary years of feelings from her real connection with the grieving widower? And as Mike and Aurora help each other overcome the tragedies of their pasts, will their friendship blossom into something more?

The poignant Canadian Boyfriend is perfect for fans of Abby Jimenez or Carley Fortune. Both Aurora and Mike have demons to face, but they find ways to laugh together and with Olivia. Readers are sure to enjoy this gentle love story. --Jessica Howard, freelance book reviewer

Discover: In this poignant second-chance romance, a woman meets a charming widower, who just happens to be the same guy she told everyone she was dating back in high school.

All Rhodes Lead Here

by Mariana Zapata

In this slow-burn romance set in Colorado, Mariana Zapata (From Lukov with Love; The Wall of Winnipeg and Me) presents the engaging story of a frustrated woman on the cusp of a new life, making All Rhodes Lead Here a perfect love story for anyone looking for a fresh start. Aurora De La Torre has been in a one-sided relationship for 14 years and finally decided she'd had enough. She left her boyfriend, who happens to be a famous country music star, and moved back to Pagosa Springs, Colo. Pagosa Springs is the home of some of Aurora's happiest and worst memories; she lived there as a child, before her mother disappeared when Aurora was a teenager.

She decides to rent a garage apartment and hopes to find a job she likes. She also plans to take the hikes from her mother's hiking notebook as an homage to the loss that still hurts 20 years later. But things go awry right off the bat when Aurora gets to the apartment, which, it turns out, was not actually listed by owner Tobias Rhodes. Rather, Rhodes's teenage son, Amos, rented it secretly, and Aurora finds herself tiptoeing around the grumpy homeowner for weeks. But slowly, Aurora's sunny charm works on gruff Rhodes, and a friendship develops between the two.

With more depth of emotion than some of Zapata's other books, All Rhodes Lead Here is a story of love, loss, and moving on. Perfect for fans of slow-paced character development, and with the vivid Colorado mountains as a backdrop, Zapata's novel is a delightful romance. --Jessica Howard, freelance book reviewer

Discover: In this slow-burn romance, a woman finds love in the Colorado mountains.

Graphic Books

What's Wrong?: Personal Histories of Chronic Pain and Bad Medicine

by Erin Williams

The likely reaction to author-artist-cancer researcher Erin Williams's compelling hybrid graphic memoir, What's Wrong?: Personal Histories of Chronic Pain and Bad Medicine, is empathic nodding: physical distress and healthcare failures seem to be universal experiences for far too many. "According to the CDC, 20 percent of Americans live with chronic pain," Williams writes. "That's fifty million people." She spent "three years talking to four of the fifty million," bookending their stories with her own unalleviated torments.

Despite decades of chasing doctors, Williams "live[s] without meaningful relief or medical consensus." Her quartet of interviewees--chosen because their stories have "historically been omitted from medical study and literature"--share her misery. Dee, Brooklyn-born with Jamaican roots, was dismissed with gynecological misdiagnoses for what would prove to be bladder cancer. Rain, a nonbinary trans artist, battles a rare, debilitating immune deficiency that doesn't qualify her for disability benefits. Gymnast Alex is one of Larry Nassar's 500-plus sexual assault victims; her paralyzing endometriosis is linked with years of heinous abuse. Adriana is recovering from the very addictions that destroyed her childhood caregiver.

Williams impressively supplements her intimate text with indelible, penetrating illustrations: a panel of medical experts are (no surprise) all men in suits; a patient garbed in Lay's potato chips packaging explains "what hospital gowns feel and sound like"; an abuse victim's detached self-awareness is presented as child's and woman's bodies overlaid in pieces. Williams, alas, has no miraculous antidotes here. What she provides is much-needed community: "We have to recover our stories, share them.... We have to hear the stories of others and believe what they say." --Terry Hong

Discover: Erin Williams bears witness to the experiences of chronic pain and healthcare failures--hers, as well as four others--in this remarkable hybrid graphic memoir.

Biography & Memoir

Dear Mom and Dad: A Letter About Family, Memory, and the America We Once Knew

by Patti Davis

When Ronald and Nancy Reagan were the U.S. president and first lady, their clashes with their politically liberal daughter made headlines. Dear Mom and Dad: A Letter About Family, Memory, and the America We Once Knew is Patti Davis's guileless and frequently stirring effort to understand the famous couple who raised her but remained elusive in their lifetimes.

Davis largely considers her parents individually: "Politics was a tangible presence, as if it had a seat at our table and competed with me for your attention, Dad"; "It's so much harder to write to you, Mom--I still fight through traces of bitterness and wrestle with the complexity of our relationship." Davis and her father had some common ground--a religious faith and a loyalty to the United States, which she feels is now so broken that, were her father "looking in" today, he'd wonder, "What has happened to the America I loved?"

Davis told her parents she regretted her notorious 1992 autobiography, "the title of which I refuse to even mention," and readers of Dear Mom and Dad shouldn't expect score settling this time around. Instead, Davis has written a kind of love letter, and her triumph is that, for all the Reagans' celebrity, she portrays her family as not so different from any other. Her goal during this "last third of my life" could be anyone's: "Our parents are part of us--the sweet moments, the difficult memories.... We find ourselves when we accept that." --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: The triumph of Patti Davis's long-form letter to her parents is that, for all the Reagans' celebrity, she portrays her family as not so different from any other.

History

Cold Crematorium: Reporting from the Land of Auschwitz

by József Debreczeni, transl. by Paul Olchváry

First published in 1950 in Hungarian, this previously untranslated memoir, which surely should rank among the greatest in Holocaust literature, is Hungarian journalist and poet József Debreczeni's searing indictment of Nazi slave labor camps. Cold Crematorium, in its first English-language edition, translated by Paul Olchváry, chronicles Debreczeni's horrific 12-month experience in a series of brutal forced-labor camps that eventually led to the "cold crematorium" hospital in Dörnhau--where prisoners too weak to work were sent to die or await execution.

At his 1944 arrival in Auschwitz, newcomers were sorted to "left" or "right" sides; Debreczeni was sent to the right while those on the left were dead within 45 minutes. Debreczeni's survival of this Nazi "Scylla and Charybdis"--his descent into bone-deep exhaustion, exposure, disease, starvation, and psychological torment as a häftling (prisoner)--represents a profound reckoning with human depravity. He observes the minutiae of camp life, including its internal economics, and the "hierarchy of the pariahs" that Nazi officials created to pit prisoners against one another for food and work privileges. The camp "kapos" and "elders" are often as heartless as their enslavers, whom Debreczeni scathingly dissects as a product of the animalistic conditions of the camps.

Cold Crematorium is a guided tour through hell, and not for the squeamish: the layers of suffering Debreczeni documents will leave readers gutted on every page. Yet his incandescent and poetic prose soars above the agony to achieve nothing less than art itself. --Peggy Kurkowski, book reviewer and copywriter in Denver

Discover: Untranslated for more than 70 years, this searing lost Holocaust memoir reaches a new global audience to reveal the inner workings and endless suffering of Nazi labor camps.

Social Science

The Cancer Factory: Industrial Chemicals, Corporate Deception, and the Hidden Deaths of American Workers

by Jim Morris

The Cancer Factory: Industrial Chemicals, Corporate Deception, and the Hidden Deaths of American Workers, the harrowing debut from journalist Jim Morris, considers a case of corporate malfeasance at Goodyear Tire and Rubber over the course of decades.

From 1957 onward, workers in the Goodyear plant in Niagara Falls, N.Y., were exposed to a chemical called ortho-toluidine. By that time, its manufacturer, DuPont, already knew it caused bladder cancer and put protective measures into place for their own production workers. Goodyear workers inhaled it and absorbed enough that it seeped from their pores. The result was one of the largest and best-documented outbreaks of work-related cancer in the United States.

Morris skillfully interweaves the history of workplace abuses and labor protections in the United States with the stories of several victims of the cancer outbreak and that of Steve Wodka, the lawyer who spent more than three decades representing them. Wodka won settlements and increased screenings for retirees exposed at Goodyear, which resulted in earlier detection for some additional cancer patients, but the lives of the affected workers remained full of lingering fear of the cancer's return. Morris's vivid accounts of their cycles of treatment and despair make heartbreakingly personal the full-picture story of the woeful inadequacy of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration's ability to protect workers against chemical exposures. This book does for factory workers in the second half of the 20th century what The Radium Girls by Kate Moore did for those in its first. --Kristen Allen-Vogel, information services librarian at Dayton Metro Library

Discover: This harrowing story of a cancer outbreak illuminates the tragic lack of protection against workplace chemical exposure in the United States.

Essays & Criticism

Why We Read: On Bookworms, Libraries, and Just One More Page Before Lights Out

by Shannon Reed

As the subtitle makes clear, Why We Read: On Bookworms, Libraries, and Just One More Page Before Lights Out presents a playful frolic through one book lover's memories of a life lived with her nose in a book. Pennsylvania native Shannon Reed (Why Did I Get a B?), hearing-impaired since childhood, was often punished for her impairment, but found friends in books: "Reading was always safe and always good company." After beginning this work by having "bitten through to the chewy nougat core of my personal answer" to "why I read," she turns this "celebration of books and reading" into a lighthearted examination of the reasons other people have for their devotion to the written word.

The result is a joyous meander through the world of book love. Chapters feature anecdotes from her years as a teacher and the books she has taught, including George Saunders's "weird but great" Lincoln in the Bardo. There are also stories about her students, among them the young man who sneered at anything other than "real books" yet misattributed Moby-Dick to Nathaniel Hawthorne. Chapters aiming for comic relief with titles like "Calmed-Down Classics of American Literature for the Anxiety-Ridden" strain to be funny, but the rest of the book is a genial collection of opinions and recollections. "Life is so much better with books than without," Reed writes. Those who agree will find welcome company in this cheerful work. --Michael Magras, freelance book reviewer

Discover: A lifelong bookworm takes readers on a lighthearted tour through her reading experiences, those of students she has taught, and the many reasons for living life in the pages of a book.

Parenting & Family

The Screentime Solution: A Judgment-Free Guide to Becoming a Tech-Intentional Family

by Emily Cherkin

The use of screens, whether in the form of phones, tablets, television, or whatever new permutation is next in the endless quest to be ever-more connected, is not remotely unproblematic--especially when the people interacting with the screens are children. In The Screentime Solution: A Judgment-Free Guide to Becoming a Tech-Intentional Family, Emily Cherkin (who also answers to the professional moniker of the Screentime Consultant) explains in empathetic detail the dilemmas that parents face in trying to stem the tide of screens surrounding their children and to model healthy use of technology themselves.

Cherkin makes clear that these issues surrounding media are not the same ones that today's parents and teachers faced when they were growing up. The addictive qualities of technology now are intentionally present, a product of what is euphemistically called persuasive design. Cherkin describes the anxiety of the families she's helped and debunks arguments that demand that children be very connected at all times. Instead, she advocates for what she calls tech-intentional lives--having guidelines and rules around allowing screens and social media to be a part of a day, instead of assuming that being online is a default setting or that people are powerless in the face of its prevalence.

At the end of each chapter, she distills her insights into actionable approaches toward integrating technology into families in a way that supports their values and children's mental health. The Screentime Solution is an invaluable resource for parents, teachers, and anyone interested in the ways in which technology has become increasingly pervasive. --Elizabeth DeNoma, executive editor, DeNoma Literary Services, Seattle, Wash.

Discover: The Screentime Solution offers a practical road map for parents looking to address the seemingly overwhelming issues around the ubiquitous presence of screens in the lives of their families.

Children's & Young Adult

Wildful

by Kengo Kurimoto

U.K.-based creator Kengo Kurimoto's graphic novel debut, Wildful, is visual storytelling perfection. The plot might seem simple: a girl and her dog meet a new friend on their daily walks. Close attention to Kurimoto's exquisitely detailed art, however, will reveal multiple layers of delightful transformation.

Wildful is divided into seven chapters, each of which begins with a similar scene of a girl walking her dog. She's utterly distracted in the first chapter but, when the dog sees a fox and barrels through the opening of a dilapidated fence, Poppy chases the pup. The first text appears: "Pepper!!" A wool-capped boy answers with "That way! He went that way!" before wrangling and returning Pepper to Poppy. "Mum, you won't believe what I just saw!" Poppy announces when she returns home, but her mother is asleep on the couch. As chapter two commences, Poppy is still distracted as she and Pepper set out, but she heads straight for the fence. This time, Poppy and the boy reunite for a wondrous birdwatching adventure. At home, Mum is awake to listen to Poppy's excitement about "the most magical place" she's just shared with her new friend, Rob. By chapter seven, the sidewalk holds four adventurers: Mum is ready to experience the healing enchantments.

Kurimoto uses pen and ink to produce his meticulous sepia-toned illustrations. He's an indisputable master of perspective, giving readers beautiful views. His insightful precision depicts Poppy's closed-eye appreciation of birdsong and the intricacies of a blooming wildflower as Rob's nostrils flare in olfactory delight. Kurimoto brilliantly manages to thread exploration, memory, renewal, and gratitude throughout his exact, ruler-straight panels. Wildful is a breathtaking, wildly welcoming achievement. --Terry Hong

Discover: Kengo Kurimoto's stunning debut graphic novel, Wildful, celebrates the wonders of nature in near-wordless visual perfection.

A Happy Place

by Britta Teckentrup

A bright little star peeks through a sleepless child's bedroom window and whispers, "Follow me... and I will help you find a happy place." So begins a nocturnal romp through nature in author/illustrator Britta Teckentrup's dazzling children's picture book. A Happy Place, with its accessible language, stunning illustrations, and playfully cut-out pages, is a delightful reading adventure for young audiences.

The glow of the star shines a guiding light in "the deep blue night" as child and star travel past a river full of herons, up rolling hills speckled with insects, and into the inviting moonlit woods. Here the nighttime explorers find a trove of friends to sing and dance with, including "a tippy-toed squirrel," "a bushy-tailed fox," and "a long-eared hare." The child celebrates this deliciously happy place with the animals until it is time to go back home to bed.

Teckentrup (Under the Same Sky) pairs her endearing prose with enchanting illustrations that light up the story's dark setting. Shadowing and fine detail add depth, texture, and intrigue making that which seems ordinary in daylight extraordinary within Teckentrup's nighttime pages. The die-cuts add extra charm to the tale, especially at the middle of the book, where they unveil the forest friends one by one, then hide them as each departs.

The star promises to watch over the child as they sleep at the book's conclusion, making it a perfect bedtime read. But night or day, A Happy Place transports its audience through the joyous magic of the natural world. --Jen Forbus, freelancer

Discover: A star leads a small child on an enchanting nighttime journey to find a happy place and new friends.

Ten Little Rabbits

by Maurice Sendak

Children's lit titan Maurice Sendak (1928-2012) needs no introduction, but for the youngest readers, the numbers do. Created as a promotional pamphlet for a museum in 1970 but never before published, Ten Little Rabbits is a brisk, sweet, and funny picture-book intro to counting that makes an audacious suggestion: there's something magical about numbers.

Ten Little Rabbits begins with a boy in a magician's getup taking the stage. He sets his upturned top hat on a pedestal, and out pops a yellow rabbit; a large numeral "1" appears low on the page--readers can't miss it. In the illustration that follows, the yellow rabbit has moved to the top of the boy's head so a second rabbit--blue this time--can pop out of the hat; the numeral "2" appears below. On it goes, up to 10, at which point the boy is alarmingly festooned with rabbits--"So then--/ he made them vanish again!" Back the rabbits go into the hat, one by one, until the rabbit tally is "none." Following a tip of his hat, the boy exits stage left: "All done."

The modesty of the book's sketch-like drawings--in black and white but for the rabbits--ensures that readers won't be overwhelmed by the central concept, although they may be overcome with amusement: not only are bunnies everywhere, but the magician wears increasingly put-upon facial expressions as more and more rabbits threaten to ruin his act. Sendak adeptly tweaks the boy's eyebrows and mouth to relay his surprise, concern, and annoyance, which is to say his relatable humanness. --Nell Beram, freelance writer and YA author

Discover: Created in 1970 and centered on a boy in a magician's getup, Maurice Sendak's brisk, sweet, and funny picture-book intro to counting suggests that there's something magical about numbers.

Pangu's Shadow

by Karen Bao

Two migrant girls team up against corruption and conspiracy to prove their innocence--and worth to science--in this gripping enemies-to-lovers space academia murder mystery.

Teenage academic rivals Ver Yun and Aryl Fielding find their laboratory supervisor dead and become suspects in his murder. Now, Aryl's parents are under house arrest without pay, and Ver no longer has help to find a cure for RCD, her painful degenerative disease. The girls, both offworlders on G-Moon One, realize their common battle ("People like us, who are different--we represent everyone who shares our blood") and work together to avoid a computer-run trial biased against their moons. Both know "the astronomical escape velocity needed to break free" of such prejudice and must risk their lives so they can live at all.

Karen Bao (The Dove Chronicles series) sets Pangu's Shadow in a distant star system in the far future, yet intertwines contemporary issues of unchecked capitalism and rampant inequality. For example, a corrupt system better maintains G-Moon One than Two and Three, and good marketing ensures an overpriced drug's profitability despite its ineffectiveness. Alternating chapters reveal the girls' awareness of this abuse; Aryl hates the "oh, how they wish they could do something to help" attitude of One-ers, while Ver says "people clucking over me makes me feel even more self-conscious about being disabled." Detective hijinks abound, including last-ditch offworld trips, and a morgue heist to find a prosthetic hand. A slow-burn queer romance and stellar worldbuilding round out this sci-fi about queer girls flipping the script. --Samantha Zaboski, freelance editor and reviewer

Discover: Queer girls from different moons team up against systemic inequality and conspiracy to prove their innocence--and worth to science--in this gripping enemies-to-lovers space academia murder mystery.

Infinity Alchemist

by Kacen Callender

National Book Award-winner Kacen Callender (King and the Dragonflies) enters the YA fantasy scene with Infinity Alchemist, an erudite novel set in an elaborately designed, hierarchical world run by the power hungry.

Eighteen-year-old, "brown"-skinned Ash wants to be an alchemist but learned when he was rejected from Lancaster College of Alchemic Science that natural talent isn't enough to break into the classist world of academia. Now Ash works in the school's gardens and practices alchemy illegally. Ramsay graduated Lancaster at 18, two years after their parents were hanged for treason. The "pale"-skinned 19-year-old is the youngest professor in the college's history and has the rare ability to switch genders, "a marker of exceptional power." After Ramsay catches Ash performing alchemy, they offer to teach the young man in exchange for help finding the Book of Source, a sacred text whose reader "would become an all-powerful alchemist." As they perform magic together that they could never accomplish solo, their mutual admiration turns into romance. But their search for the Book of Source is a towering problem for the magical aristocracy, who are willing to kill to retain power.

Callender includes the perspective of a third teen, Callum, in this novel of empowerment and self-acceptance to give readers a view from all levels of the magic society. The author creates teens who are rounded individuals, each maturing and developing alone, and eventually as part of a non-monogamous triangle relationship. This novel should thrill and enchant fans of Garth Nix's Angel Mage and Aidan Thomas's Cemetery Boys alike. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Discover: National Book Award-winner Kacen Callender enters the YA fantasy scene with this erudite novel set in an elaborately designed, hierarchical world run by the power hungry.

Coming Soon

The Writer's Life

Francis Spufford: Taking the Family Business in an Irresponsible Direction

Turning facts into fiction has gained British author Francis Spufford enviable international awards and praise. In his brilliantly immersive third novel, Cahokia Jazz (Scribner, $28, reviewed in this issue), he presents an alternate U.S. history spotlighting a predominantly Indigenous Midwest metropolis in 1922 fighting for its continued existence.

Turning facts into fiction has gained British author Francis Spufford enviable international awards and praise. In his brilliantly immersive third novel, Cahokia Jazz (Scribner, $28, reviewed in this issue), he presents an alternate U.S. history spotlighting a predominantly Indigenous Midwest metropolis in 1922 fighting for its continued existence.

You began your authorly career focusing on nonfiction, then switched to writing novels in 2016. What prompted the change?

I'd always been a nonfiction writer of a very narrative kind, stealing techniques from novels wherever I could. A point came when I realized I wanted the rest of what fiction can do, and that it was only a kind of cowardice holding me back. But there was some loss as well as gain in making the changeover. There are ways that nonfiction can take a grip on the real, and fascinating, and stubborn, and contradictory world that fiction can't. I stand by my earlier enthusiasm for nonfiction as a form, even if I've moved off to do something else.

Your three novels thus far each combine real events/places with stories you create: mid-18th-century Manhattan in Golden Hill, the 1944 New Cross attack in London in Light Perpetual, and now Cahokia Jazz. What inspires you to rewrite history this way?

I think it's because, thanks to the path I followed to get to the novel, I'm now a writer of fiction who tends to find the starting point for their imagination in a factual thing. An unexpected historical event, or a place--very often a place, I'm a place-driven guy--but at any rate something granular, gritty, for me to grind away at. But what I want to do now is to explore them in story. Why history? Probably this has something to do with coming from a family of historians. Both my parents were history professors, professionally and imaginatively concerned with medieval money (my father) and 17th-century village life (my mother). The past was always... present. You could see me as the black sheep of the family--the one who took the family business in an irresponsible direction, by making things up.

Cahokia Jazz is your second novel set Stateside, this time centering an Indigenous community. Were you, as a white British writer, ever concerned about potential comments/criticisms citing cultural appropriation?

Cahokia Jazz is your second novel set Stateside, this time centering an Indigenous community. Were you, as a white British writer, ever concerned about potential comments/criticisms citing cultural appropriation?

It seems to me fundamental to what fiction is that writers should write about what they haven't personally experienced. That's non-negotiable. But it doesn't cover the issue of power involved, and of who gets to represent, and who gets to be represented. I did, very much, worry when writing Cahokia Jazz, not so much about accusations of cultural appropriation as about the thing itself. In the end, my sense that it was okay to go ahead rested on two things.

One, that the Indigenous people in the book do not correspond to any existing Native American nation or people. They are a projection of what might have been, had the situation witnessed by [Spanish conquistador Hernando] De Soto on the Mississippi in the 1540s continued: the large towns populated by maize farmers, busy working out the next evolution of the Mississippian cultural complex. In our world, all that got destroyed by disease. In the book, it's continued, changing for five more centuries and fusing itself with a mass of outside influences, especially including a weird Catholicism. So it's not that I am speaking for a culture that ought to be speaking for itself. I'm conjecturing a culture that never existed. I hope that means I'm not pushing aside anyone else from the microphone.

Then, two, I'm an outsider. I'm not a Native American, or an African American, but I'm not a white American, either. It's all foreign to me. I think there's a freedom in that, to speak from somewhere off the usual map. I hope I make good use of that freedom in the book. That's what will justify it, or not.

The breadth of research required to create Jazz is astounding. How did you choose the "real" elements of your fiction? How did you conduct the research?

I love the process of research, so it's a treat for me, not a burden. In fact, I often have to tear myself away from the pleasures of finding-out, to make myself do the work of writing-down. But having said that, I'm not a historian. (Sorry, parents.) My task is never to find out everything that can be known about a subject, only to find out enough about it to tell the story. Only to find the right details to make an imagined world solid. It's an art of illusion. You develop an eye for what will work, an ability to swoop quickly on the promising single data-point from which the illusion can be woven. It's less laborious than you'd think. I'm a crow looking for shiny things, not a patient reconstructor.

Your ending "Notes and Acknowledgments" was such an entertainingly illuminating gift after an already spectacular read. This, especially: "what makes this altered America in this 1922 different is that, in this timeline, it was the variola minor or Alastrim form of smallpox that came out of West Africa first, and was carried across the Atlantic in the 'Columbian exchange.' " A single, microscopic germ with a 1% death rate could have changed all of history. How did you discover such a minuscule fact?

Minuscule, but with huge implications. Honestly, this stuff is there in plain sight. Charles Mann's 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created has got a good discussion of the disease history to start off with, and then if you want to dig deeper there's Ann Ramenofsky's Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact.

On a wider subject--I really like using a "Note" or another bit of a book's apparatus, apparently outside the story, to add a sly extra element to the story itself. (Probably the result of reading Nabokov's Pale Fire at an impressionable age.) Anyone who ends Cahokia Jazz itself feeling sad should check out the record recommendations at the end of the Note for some in-world consolation.

Your opening dedication to Professor Kroeber's late celebrated, iconic daughter... I shouldn't give away her identity here. You mention, "She wouldn't necessarily approve of the foundation on which this particular ambiguous utopia stands." Did you know/meet her before she passed? What do you think her reaction might have been to your characterization of her father? Any guesses as to what she might have thought of your book?

I never met the icon in question, to my sorrow. She was due to come to a panel discussion on utopias in London that I was also involved in, but this was towards the end of her life, and she decided against the long flight. But her work has been a familiar and wonderful presence in my life ever since I was a child reading--oh, this is ridiculous--The Wizard of Earthsea, and it's Ursula Le Guin we're talking about. Obviously!

I'd hope that she'd enjoy Cahokia Jazz as a piece of making and imagining: she was a person with a large and eclectic capacity for taking pleasure in verbal artistry, and a lot of what I'm doing with the city of Cahokia in the book is strongly influenced by her way of creating the imaginary gardens in which real toads, and stories that matter, can be found. Where I think she'd dissent, maybe, is from my sense that the heavily qualified good place (eu-topos) that my Cahokia is can come about because a price is being paid for it in innocent blood. She was interested in utopias, politically and as a literary form, but her great thought experiment of a story, "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas," shows her refusing the idea that utopia can ever be acceptably paid for in suffering. I mostly agree with her. I certainly detest the ways in which our good life in the rich world now is paid for by misery elsewhere. But I have a sense, probably ultimately a religious one, that just sometimes, when the sacrifice is voluntary, blood may be the needful thing to make our walls stand.

As for the picture of her father: oh, I hope she'd like it. I took it as far as I could from her mother's memoir of him, and from her own short story, "Imaginary Countries," where her memories of her 1930s childhood summers in Napa Valley have been relocated to imaginary Eastern Europe, and there's the tenderest portrait of happy small girl and older academic father. He was clearly much loved.

Your books are bestsellers on both sides of the Atlantic. Would you say your audiences' reactions differ significantly by geography?

Maybe in this respect: when I'm writing about America, in Golden Hill and now in Cahokia Jazz, my British readers tend to respond as if what's happening is some enjoyable tropes being laid out. The tropes of 18th-century lit, before, and now the tropes of the 1920s crime novel. Men in hats and femmes fatales. But for Americans, the test is whether my stuff is recognizable. Whether, in its weird and oblique and history-twisting way, you can read my books and say: yeah, this isn't what I was expecting, but this is us. This is recognizably about the real place we live, even though it's written from the peanut gallery where the rest of the world gazes at America, and wonders about it, and worries about it. I hope Cahokia Jazz passes that test.

Your groupies must know: what might we expect next?

A fantasy novel set during the London Blitz--which, for the first time ever in my fiction, looks as if it's going to need a sequel. --Terry Hong

Book Candy

Book Candy

Open Culture checked out "10 magnificent historical libraries (that you can still visit today)."

---

CrimeReads featured "planes, trains, and homicides: murder mysteries in transport."

---

Mental Floss recalled "when McDonald's went to war with the dictionary."

The Women

by Kristin Hannah

A bright young nurse enlists in the United States armed forces during the Vietnam War with the hope of making a difference, and faces the horrors of war and the turmoil of returning home in The Women, an epic, yet intimate, and heart-wrenching historical fiction saga by Kristin Hannah (The Four Winds). Through meticulous research and intricate character development, Hannah resurrects the voices of war's overlooked heroes: the women.

Twenty-year-old Frances "Frankie" McGrath has grown up with all the advantages her father, a California real estate developer, can afford. Her upbringing and parochial school education have "instilled in her a rigorous sense of propriety," and her mother urges her to slow down at nursing school and focus on finding a husband. The social unrest in the United States in 1966 seems far from her sheltered life, as does armed conflict in Vietnam. Her father has raised Frankie and her older brother, Finley, on stories of their family's military service and keeps a "wall of heroes" with photos of male relatives in uniform, though he himself was unable to serve. When Finley ships out for Vietnam with the Navy, Frankie feels left behind until Finley's best friend Rye makes an astonishing pronouncement: "Women can be heroes." When she realizes nurses can serve in the military, Frankie races to enlist, too. She hopes she and Finley might serve together, but her plan hits a snag: the Navy won't take a nurse without hospital experience. So Frankie signs on with the Army, too naive to understand the implication of its readiness to accept her--they are desperate, being on the front lines. She's shocked when her parents find her enlistment embarrassing and foolish. "It is not patriotic to do something stupid, Frances," her mother says. Then two naval officers come to their house bearing news of Finley's death in action. Frankie's family is broken by the tragedy, and for the first time, Frankie understands the danger in her choices.

Arrival in Vietnam gives Frankie a quick series of rude awakenings. Her plane draws gunfire, she unwittingly drinks unsafe tap water, and she must jump from a hovering helicopter while wearing regulation Army pumps and an excruciatingly uncomfortable panty girdle. A mass casualty event shortly after her arrival at her assigned evac hospital plunges her into a nightmare of blood, chaos, and destroyed young men. The wounded pour into the ER and are sorted by whether or not medical help can save their lives. As she adjusts to life "in country," she is supported by fellow nurses Ethel, a horse-loving Virginian, and Barb, an African American from the Deep South. Frankie sees life and death up close as she tends to soldiers and Vietnamese villagers. Updates from the home front come in letters from her mother, who complains of the protests brought on by the civil rights and anti-war movements and warns her daughter, "The world changes for men, Frances. For women it stays pretty much the same."

Until her homegoing in 1969, Frankie grows as a nurse and as an independent woman, strengthening lifelong friendships, and falling in life-changing love. War may be hell, but what she finds when she returns home is no paradise, either: a country furious about the Vietnam War and taking out its anger on veterans; a family that wants to pretend she never went to war; and hospitals that don't consider her work experience valid. Adrift and struggling with the aftermath of her experiences, Frankie is left wondering why her service to her country is treated like a mark of shame at best, and a lie at worst, and how she can ever move forward.

Frankie begins the story as crisp and clean as a fresh sheet of paper, but her innocence is quickly smudged, creased, and ripped until she crumples. Hannah shows readers that even if a crushed page can never be fully cleaned or smoothed, it still has space to hold a beautiful story. Like the real women who served as nurses in Vietnam, Frankie comes home to a lack of support and recognition. Even when she reaches out for help, she is told to forget the war or, amazingly, that no women served in it. This erasure of her work and sacrifice will likely elicit gut-wrenching anger and pity from readers, but Frankie is fortified by the power of enduring female friendships. The turbulent late 1960s and disillusioned early 1970s serve as a rich backdrop for her personal story, and Hannah works in an enormous amount of atmospheric detail, pop culture references, and historical fact without ever turning the novel into a civics course.

Through the lens of Frankie's point of view, Hannah sensitively reckons with the tangle of horrors and heroism attached to one of the United States' most controversial military conflicts. Book clubs, fans of epic stories with deep character work, and anyone curious about the vital, often ignored contributions of women in war will fall in love with The Women. --Jaclyn Fulwood

Uncovering Women's Lost Histories

An Interview With Kristin Hannah

|

|

| (photo: Kevin Lynch) | |

Kristin Hannah is an award-winning, number-one bestselling author with more than 25 million copies of her books sold worldwide. Her most recent titles, The Four Winds, The Nightingale, and The Great Alone, won numerous awards and her earlier novel, Firefly Lane, became a top series on Netflix. Hannah is a lawyer-turned-writer and the mother of one son; she and her husband live in the Pacific Northwest near Seattle. Shelf Awareness recently chatted with Hannah about heroism, the tumult of history, and The Women (St. Martin's Press, $30), a story of a young woman who goes to the Vietnam War, and the nurses who served there.

You were still a child when the Vietnam War happened. What was your impression of it at the time?

It had a profound impact on me at the time and over time. I was of the age that my friends' fathers were going to Vietnam. There was a lot of talk at the kid level about that. We were watching it as a family on the news in the evening. There were only a couple of networks, so it was front and center. I had a girlfriend from elementary school whose father was shot down in 1967. I began wearing one of those MIA/POW bracelets that we wore back then. They had the name of a military person, and when he was lost, you would wear this bracelet until he came home. I wore mine for years and years and years. Later, when I was older, it became apparent to me how the returning vets were treated, how the country felt about the war, and how the country felt about the warriors.

What historical perspective did you have when you started this project? What made you feel so strongly about telling the story of women in the war?

Writing The Nightingale was the first time I understood that I was drawn to women's lost histories in time and that, when we read about them, everything came from a male perspective. I began seeking out women's stories. It coincides roughly with me turning 50. I began to look at not only my life in retrospect, but the world in retrospect. I tried to figure out what I had to say to my daughter-in-law, to my granddaughter, and to kids. I first proposed this book to an editor in 1998. That's how long I have wanted to write it, but I always felt that I didn't have enough gravitas to look back at this time period that was so seminal for me and for the country. In the last few years, it's been impossible to ignore the great divide in American politics and the differing ways that people feel about our country. It brought up Vietnam to me, because that time felt very volatile, very turbulent. I thought, "Okay, this is the moment where I'm going to write this book that I've always wanted to write." It's terrifying, because it's a big topic. So many people that I am writing to lived through it, and are at an age to understand it better than I'm able to through research and interviews. Once I began to look at the Vietnam War from a female perspective, I realized this was an incredibly important story that needed to be told. I wanted to tell it while the nurses could still read it.

Why do you think the heroism and contributions of women are so minimized?

It speaks to a larger question: Why is the heroism and courage of marginalized people forgotten? It comes down to who was writing the books, who was telling the stories, who was looking for the stories. When I do research, the stories are out there. They just aren't picked up. I'm happy to be living in a moment when other stories and other voices are being heard and celebrated.

What gave you the ambition to tell a story with so much history and depth?

That was the struggle from the get-go. How do I take this huge, complex historical situation, which so many people remember, which had so many facets that didn't have the good and evil of, for example, World War II, that didn't have the clarity of some historical periods? How do I say what I have to say about the war--America, women, coming of age. The answer was the creation of this character, this one woman, and to look at the entire landscape through her eyes. I created characters like Barb and Ethel to expand her worldview and to open it up a bit and to teach her that there was more to the world than what she had grown up seeing in her sheltered family. It's one woman moving through history even as she is trying to grow up and find out who she is.

How did you develop the character of Frankie?

Frankie represents a large number of the nurses I spoke to. A lot of the women who became nurses and went to Vietnam voluntarily were very sheltered. This was the '60s. They were taught to be a certain kind of woman, a lady, and to look for marriage as their ultimate goal. I wanted to speak to that. She was a kind of woman that I understood deeply. I knew she would represent this story of getting to Vietnam and realizing, "I'm not in Kansas anymore, and what did I sign up for?" And then the story would go on through the evolution of her strength and her durability, and her breakdown, which comes in large part because not only was there little help for any Vietnam vets, there was no help for female vets. I've written about war from various perspectives, but something I feel strongly about is our country's responsibility to care for our veterans and their families in whatever manner they need.

For me as an author, Frankie finding herself, owning her own past and believing in who she is, and being able to stand up and say "I was there"--I'm proud of it. It felt like such an important and empowering arc.

What do you hope readers will take from this story?

I had a fascinating first read early on from a bookseller who wrote me a long letter explaining about her father who had been in Vietnam. He had stepped on a landmine and been badly injured. He came home, and his pain, his injury, and his service became a confusing and difficult time for her as a young girl. She said she spent her whole life working through her father's Vietnam service and what it did to their family. She said, "But in all those years, never once did I think about the nurses who saved him." I want people to recognize these remarkable women, eight of whom died, who put their lives, their youth, their patriotism, and their emotional health on the line to help others. Coming out of Covid and once again seeing the medical community paying such a personal price to help others, it's important that we all recognize this service and show gratitude for it. --Jaclyn Fulwood

Rediscover

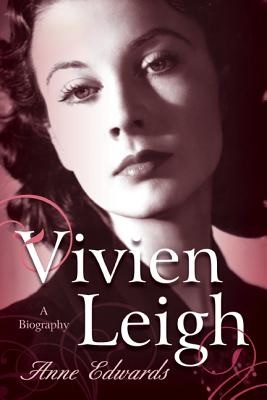

Rediscover: Anne Edwards

Anne Edwards, "a prodigious and peripatetic author who published bestselling books about the actresses Vivien Leigh and Katharine Hepburn as well as 14 other celebrity biographies, eight novels, three children's books, two memoirs and one autobiography," died January 20 at age 96, the New York Times reported.

Anne Edwards, "a prodigious and peripatetic author who published bestselling books about the actresses Vivien Leigh and Katharine Hepburn as well as 14 other celebrity biographies, eight novels, three children's books, two memoirs and one autobiography," died January 20 at age 96, the New York Times reported.

A child performer on radio and the stage, Edwards sold her first screenplay in 1949, when she was 22 (the movie Quantez, released in 1957); her first novel (The Survivors) in 1968; and her first biography (of Judy Garland) in 1975. Her Vivien Leigh: A Biography (1977) spent 19 weeks on the Times's hardcover bestseller list.

Known as the "Queen of Biography," Edwards also wrote biographies of, among others, Sonya Tolstoy, Maria Callas, Ronald Reagan, Barbra Streisand, and Diana, Princess of Wales. Her novels included Haunted Summer (1974), about the author Mary Shelley and the poet Lord Byron, which was adapted into a film in 1988.

Her family moved to California in the late 1930s at the invitation of an uncle, Dave Chasen, a comedian whose West Hollywood restaurant, Chasen's, drew celebrities. Edwards appeared onstage in children's acting, singing, and dancing ensembles and tap-danced on radio, but, as she wrote in her autobiography, Leaving Home (2012), "My dream was never to be a star (or even a supporting player) but to write."

Her screenwriting credits include the British thriller A Question of Adultery (1958), starring Julie London, which was released in the U.S. as The Case of Mrs. Loring; as well as early and unused drafts of the screenplay for Funny Girl (1968).

Edwards, who was president of the Authors Guild in 1981, lamented the dearth of women working in creative roles in Hollywood when she was starting out.

Regarding her autobiography, Edwards said in 2013: "There comes a time, and I am at that age, when you have to take your life in your arms and hold it to you to keep it breathing. It was a necessity.... Writing is a lifeline to me. I need it to breathe."

| Advertisement Meet belle bear! |