Radiance of Tomorrow: A Novel

by Ishmael Beah

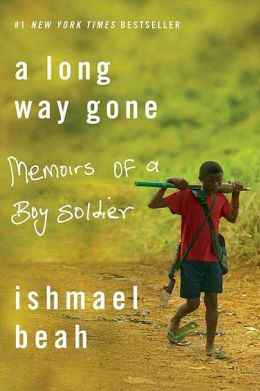

Ishmael Beah made his mark in 2007 with the publication of A Long Way Gone, his striking memoir of the time he spent as a boy soldier in war-torn Sierra Leone. More than a haunting, harrowing personal account of the effect of war on himself and the thousands of other children forced into almost unimaginable circumstances, Beah's memoir offered a vivid portrayal of the effect of brutality and violence on the consciousness of communities caught in its wake. With Radiance of Tomorrow, his first novel, Beah revisits Sierra Leone to examine not only what happens to those communities devastated by war, but also to their traditions and the outlook for their future. "I wanted to have people understand how it feels to return to places that have been devastated by war," Beah writes in his author's note, "to try to start living there again, to raise a family there again, to rekindle some of the traditions that have been destroyed.... How do you try to shape a future if you have a past that's still pulling at you?" But what begins as a story of survivors returning to what used to be home and attempting to reconstruct the rhythms of normal life takes several surprising turns as Beah carefully unfolds his elegant and layered narrative.

The setting for Radiance of Tomorrow is the (real) town of Imperi in Sierra Leone. The novel opens with an older woman, Mama Kadie, returning on foot to what used to be her home and dreading what she might find: "The name of her land had been released into the ears of the wind even with her bewildered question. She found her feet again and began walking around the town. There were bones, human bones, everywhere, and all she could tell was which had been a child or an adult." Mama Kadie is soon joined by old friend Pa Moiwa and then Pa Kainesi. Together, these three village elders clean up what they can of Imperi, much of which entails burying the bones of their relatives and neighbors that have been lying in the streets for seven years. After about a month, groups of people start returning to Imperi, or simply stopping and staying there after literally walking for months. In this way we meet Bockarie, the character at the heart of the novel, a schoolteacher and bellwether of the new community, and Colonel, a take-charge young man hardened by his experiences in the war. Here, too, Beah presents an essential conundrum of war's aftermath--the victims and victimized (sometimes interchangeable) living side by side. Among Imperi's new inhabitants are Silas, a man who, along with his children, had one of his hands amputated by a child known only as "Sergeant Cutlass." Not long after Silas and his family arrive in Imperi, so does Sergeant Cutlass.

Despite the obvious difficulties of "returning to normal" and indeed the impossibility of ever transcending their losses, the residents of Imperi manage to build a community. Families assemble, houses are reconstructed, and a school is opened where Bockarie and his friend Benjamin become teachers. And one of the town's most important traditions--oral storytelling--is resurrected. But just as the town regains its footing, the lives of its residents are disrupted (albeit more subtly) again. The first hint of trouble comes when Bockarie and Benjamin discover that the school's administrator is corrupt and stealing salaries--and they are powerless to stop it. Far worse, a mining company looking to extract the profitable mineral rutile (often found alongside diamonds) moves in nearby and sets in motion a destructive chain of events. Runoff from the mining pollutes the town's water and destroys local jobs. Lured by the promise of work (which turns out to be deadly in many cases), children quit school to go labor in the mines. The mines also draw in an unsavory element and a series of brutal rapes brings horror to an already reeling village.

The efforts of the elders to negotiate with the owners of the mining company come to no avail and soon the only solution to an entirely new set of atrocities seems to be violence once again--this time perpetrated by Colonel. It is a testament to Beah's skill as a storyteller that he manages to convey the moral ambiguity of these acts. Faced with a series of impossible odds, Imperi begins to disassemble once more. "Tradition," Beah writes, "can live on only if those carrying it respect it--and live in conditions that allow the traditions to survive. Otherwise, traditions have a way of hiding inside people and leaving only dangerous footprints of confusion."

There is no clear path forward for Beah's characters; at the end of the novel those who have survived (and many of them don't) are still moving, still searching for the titular "radiance of tomorrow" that they trust lies beyond the dawn. Though the future is even more clouded and uncertain than it was at the beginning, the characters carry their tradition--their humanity--within them and it sustains them. Through their graceful endurance, Beah shows us the beauty and resilience of the human spirit. --Debra Ginsberg

Radience of Tomorrow is also available as an unabridged audiobook (6 CDs, 8 hours; $29.95 ISBN 9781427233400). Listen to author Ishmael Beah read the author's note here.

On a related note, A Long Way Gone has been a great success, both critically and commercially. Do you feel any pressure to match that success with Radiance of Tomorrow? Have your expectations for yourself changed?

On a related note, A Long Way Gone has been a great success, both critically and commercially. Do you feel any pressure to match that success with Radiance of Tomorrow? Have your expectations for yourself changed?