You've said that The Guardians of Childhood has been 20 years in the making. Weren't you working on Santa Calls right around then?

You've said that The Guardians of Childhood has been 20 years in the making. Weren't you working on Santa Calls right around then?

Absolutely. Santa Calls was supposed to be the first in this ongoing series. At a certain point, the plot of Santa Calls was going to intermingle with the Sandman and the Man in the Moon, but it felt like I needed to pull back and introduce each myth.

The illustrations for your books are so cinematic that it's almost as if you design a movie set and then the characters walk onto them. Do you "meet" the characters first and then create a setting for them?

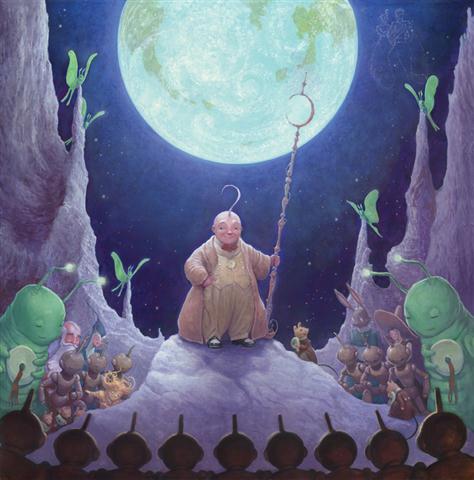

The mythologies for the individual Guardians have evolved and changed a lot over the years. The Man in the Moon is the closest to my original idea of what his world would be like and how his story would play out. There was a long gestation where I was figuring out what each of [the Guardians'] story arcs would be like. As I began to figure out their intermingling, their personalities took on a life of their own. Santa was the wild Cossack warrior in his youth, and the most accomplished bandit in all of Russia, but he has a fundamental change of heart. I got into early Russian architecture for his origins adventure. The Man in the Moon is watching over these guys long before they come into their own, and sometimes helps guide their lives to help them become the icons they would become.

Were you working on the film Rise of the Guardians (due out fall 2012) and the books simultaneously? Did one act as a catalyst for the other?

Virtually every studio had bid on the Guardians idea at one time or another. I wanted to do the books first, then have the movie come out. And to control the publishing. Books are my first love and I wanted the freedom to tell the stories fully. I didn't want this to be a movie with one tie-in book. All of them said, "That sounds good, but we can't let you do what you want to do. That's not the way we work." DreamWorks was the only studio that trusted that we share a vision. So we made a deal. Then I thought, "Now I have to do the books!" It was the catalyst that got me started after 20 years of developing the idea. These first books are about how the Guardians came to be, and the movie will be about who they are once they've become Guardians. They come together to fight Pitch. I've given them proper names that echo who they are: Nicholas St. North, E. Astor Bunnymund, Sanderson Mansnoozy. None starts out heroic. They're all goofing around, but they need to channel their energy somehow--they each have a weakness and an inner struggle.

Tell us about your media.

Tell us about your media.

I used virtually every medium I'm good at. The undercoats were often done in acrylic, and the detail work in oil. Then we'd scan that. I'd scan the images and do the last bit of color and detail work digitally. I've learned to love painting on the computer. There are some things that are easier to do, to get luminescence for instance, on the computer. I can put a thin wash of color over the whole painting, which is what I've always done, but it would take four to five hours to prepare the paint, and get the linseed oil to get the coating just right. It was a real crap shoot to see if it worked, and sometimes it didn't, and you had to wait for it to dry. Digitally, you can do something and experiment endlessly. You can zoom in with a closeness that's impossible to do with the human eye. It's perfect for someone who's anal like I am. There are a few pieces that are totally digital, and you really can't tell the difference. It took me probably a year to get halfway decent at using the tools that appear in these compositions. I miss the tactile thing of having a finished painting that exists as something on canvas. Now I have printouts; I loved painting the old way. I miss that. It bugs me. But it frees me up in ways. I thought, "It's going to take me two years on each book, how am I going to manage that?" This way I can keep to a publishing schedule that makes sense.

You have these very concrete aspects of life, such as the normal routine for MiM, and then these otherworldly aspects, like the Moon Clipper, the Lunar Moths and the fabulous lunar landscape.

I'm saying, "This guy had a life, just like yours, dear reader. He was small once, and these are the things that happened to him. He had bedtime, and food, just like every kid." It seems like that would make him more real, along with all the splendor and the fantasy. Someone told me that they'd never talked with their kid about the Man in the Moon. Even the main guys, the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus, were getting diminished. One of the things I say a lot is, we have a mythology for Superman and Batman, but we don't have a mythology for the guys we actually believed in, and that seems wrong. I wanted to make them real, make them feel like they had troubles and triumphs.

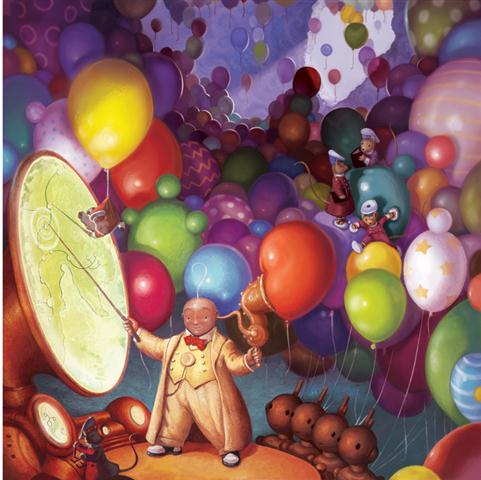

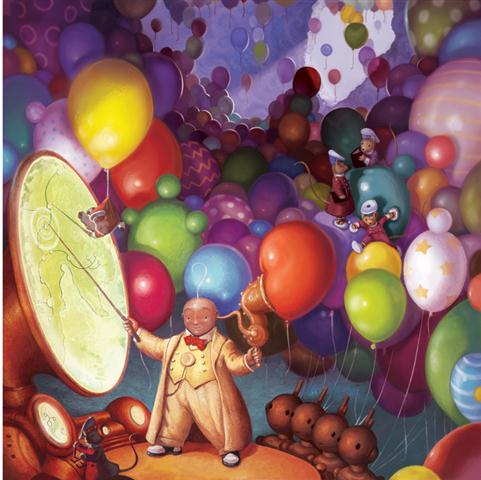

What was the inspiration for balloons as the carriers of children's dreams?

What was the inspiration for balloons as the carriers of children's dreams?

I'd just watched The Red Balloon, the movie from the 1950s. There's a haunting image at the end of the movie when the balloons are floating down to the boy. You see a balloon floating and you think, there's a kid somewhere who's really bummed out because his balloon got away. But what if something cool happens to it? I wanted kids to think when you lose your balloon, it doesn't go pop, it goes on an amazing journey, and the Man in the Moon knows who you are and what you're thinking. I love making those everyday things in life magical and mystical.

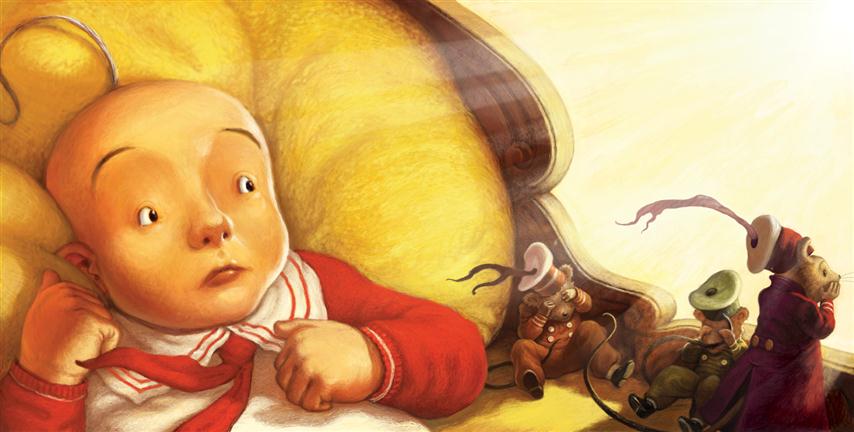

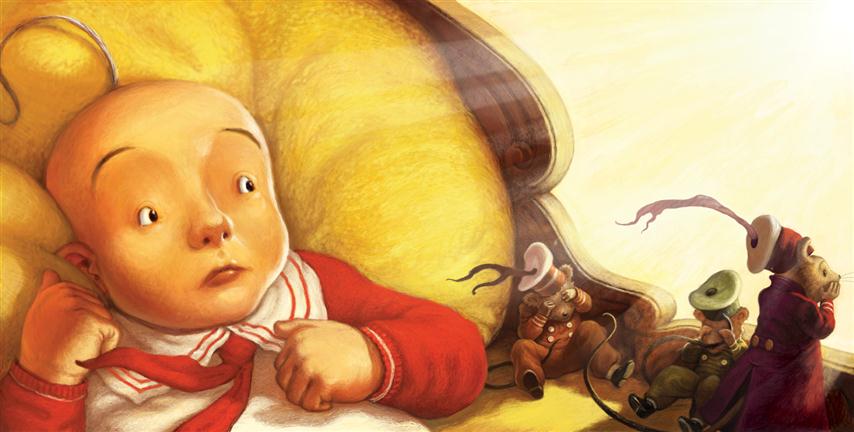

In that fabulous wordless spread where MiM's reacting to the blast, he doesn't look afraid.

Babies don't know what's scary yet. That's why they fall off the edge of the bed and reach for the scissors and don't know that fire hurts. That's what that expression is about. There is also an MGM aesthetic there, which comes from Munchkinland. One of my main influences is the costume designer named Adrian, who did the costumes for MGM musicals. He's probably been as big an influence on me as Sendak or Beatrix Potter.

There's a lovely echo of familiarity in the closing lines of the oath Nightlight repeats about guarding MiM, "For he is all that we have, all that we are, and all that we will ever be." It's reminiscent of the motto in Toyland in Santa Calls, "The best of the old. The best of the new. The best that is yet to be." Both suggest a faith in the future. Is that an important message to impart to children?

Absolutely. I watched too many Frank Capra movies growing up. I'm obsessed with the optimism of the 1939 World's Fair, where they thought in the future everything's going to be great, but by the end of the fair, World War II had begun. There's something delicate and sad about that. It echoes back to Dorothy, who's been through this amazing and horrible stuff, and she returns to Kansas and things are worse than they were at the beginning. But she's like, everything's going to be okay. Her attitude is heartbreaking. She knows she has to cling to optimism or she can't go on. For kids, I like to give them pure optimism. There's a ton of stuff in the stories that show the Guardians in trouble, but if you're a kid, after you've read a story you should think, yeah, it's tough, but if we keep the course, we'll be okay. It's something you need to hold onto.

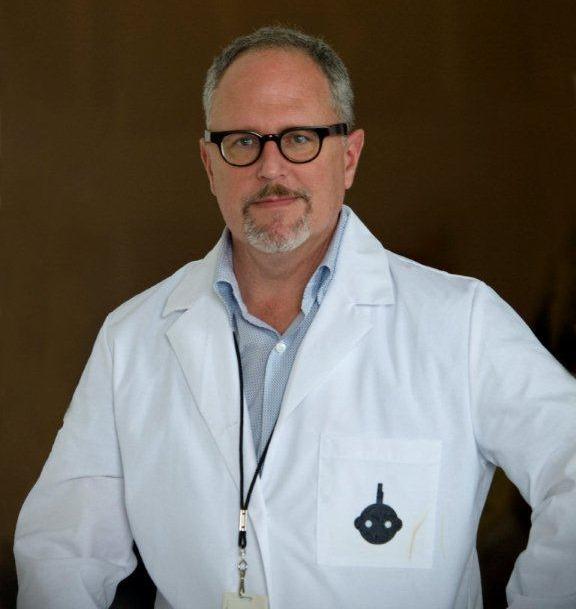

"It's almost like things ripple forward," said Atheneum editorial director Caitlyn Dlouhy, describing the process of editing a manuscript by William Joyce. With most authors, she receives an entire completed manuscript. But, she said, Joyce thinks in movie frames. "He has this brilliant way of seeing the entire arc for one chapter, and he needs to stay with it until it can't get any better," she said. "As he's finessing, he's bringing in better ideas for what the future is going to be."

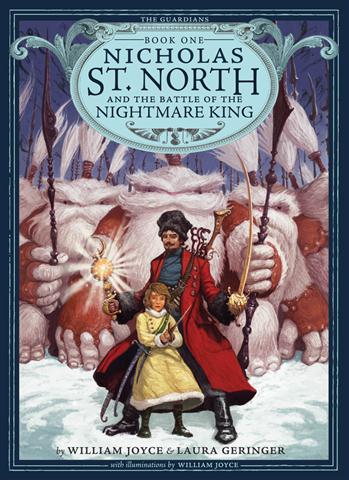

"It's almost like things ripple forward," said Atheneum editorial director Caitlyn Dlouhy, describing the process of editing a manuscript by William Joyce. With most authors, she receives an entire completed manuscript. But, she said, Joyce thinks in movie frames. "He has this brilliant way of seeing the entire arc for one chapter, and he needs to stay with it until it can't get any better," she said. "As he's finessing, he's bringing in better ideas for what the future is going to be." This is not the first time Dlouhy has worked with Joyce. She and Laura Geringer (whose imprint appears on the title page of The Man in the Moon, and who co-authored the first chapter book in the Guardians series, Nicholas St. North and the Battle of the Nightmare King, with Joyce) worked with the author-artist on The World of William Joyce Scrapbook. "I marveled at how, when Bill had his pick of where he could have done the Guardians film, he wanted to keep the books separate," Dlouhy said. "These are inception stories; they're not even prequels. Here's something that explains why these mythologies are important."

This is not the first time Dlouhy has worked with Joyce. She and Laura Geringer (whose imprint appears on the title page of The Man in the Moon, and who co-authored the first chapter book in the Guardians series, Nicholas St. North and the Battle of the Nightmare King, with Joyce) worked with the author-artist on The World of William Joyce Scrapbook. "I marveled at how, when Bill had his pick of where he could have done the Guardians film, he wanted to keep the books separate," Dlouhy said. "These are inception stories; they're not even prequels. Here's something that explains why these mythologies are important." You've said that The Guardians of Childhood has been 20 years in the making. Weren't you working on Santa Calls right around then?

You've said that The Guardians of Childhood has been 20 years in the making. Weren't you working on Santa Calls right around then? Tell us about your media.

Tell us about your media.  What was the inspiration for balloons as the carriers of children's dreams?

What was the inspiration for balloons as the carriers of children's dreams?

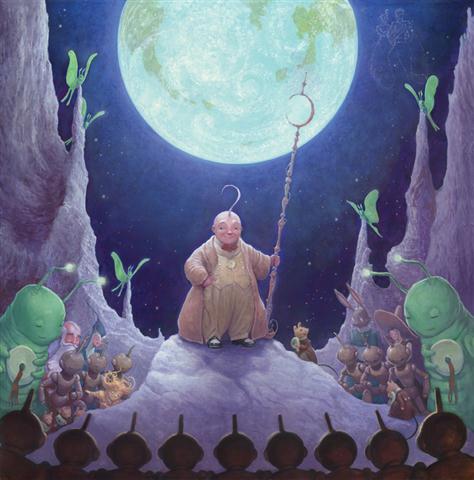

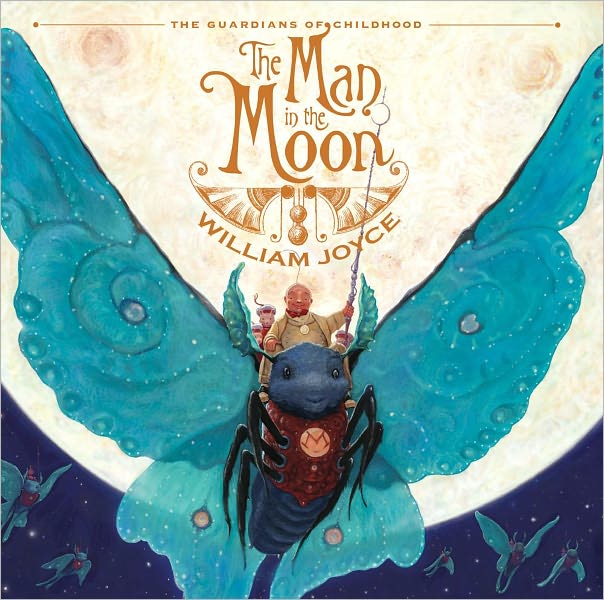

William Joyce invents a breathtaking landscape for his history of the original guardian of childhood: the Man in the Moon. As a baby, the little Man in the Moon, or MiM, as he is called, travels the intergalactic skies in the golden-sailed Moon Clipper with his mother, father and Nightlight, a kind of fairy godfather. Each night, the vessel transforms into the Moon. With the aid of a telescope, MiM's father introduces him to "the wonders of the heavens," while MiM's mother reads to him by the light of giant Glowworms, as Moonmice join the audience. Nightlight watches over the baby as he sleeps. With his open face and

William Joyce invents a breathtaking landscape for his history of the original guardian of childhood: the Man in the Moon. As a baby, the little Man in the Moon, or MiM, as he is called, travels the intergalactic skies in the golden-sailed Moon Clipper with his mother, father and Nightlight, a kind of fairy godfather. Each night, the vessel transforms into the Moon. With the aid of a telescope, MiM's father introduces him to "the wonders of the heavens," while MiM's mother reads to him by the light of giant Glowworms, as Moonmice join the audience. Nightlight watches over the baby as he sleeps. With his open face and  single perfectly placed curl, MiM resembles an otherworldly Gerber baby.

single perfectly placed curl, MiM resembles an otherworldly Gerber baby. Fans of Joyce's oeuvre will note the parallels with his earlier tour de force about a mythic man in a magical land, Santa Calls. Santa rides in his sleigh; MiM flies on his moth. The Dark Queen and her Dark Elves threaten Santa's mission, just as Pitch and his Nightmares pose a challenge to MiM's utopia. Santa learns of children's wishes through letters; their hopes and dreams travel to MiM by helium balloons. The author-artist makes brief reference to the Man in the Moon's team of helpers on "the little green and blue planet" (the other Guardians, who will get their own spotlight in upcoming books). When MiM comes up with a solution to children's nighttime fears, he enlists the aid of the Moon's minions and his team of earthling Guardians (in addition to Santa, the Tooth Fairy, the Easter Bunny, the Sandman, etc.). What happens to Pitch and Nightlight remains to be explored in subsequent episodes, but this first adventure offers a visual feast and a complete mythology of the Man in the Moon, and his mission to dispel the nightmares of the children on earth.

Fans of Joyce's oeuvre will note the parallels with his earlier tour de force about a mythic man in a magical land, Santa Calls. Santa rides in his sleigh; MiM flies on his moth. The Dark Queen and her Dark Elves threaten Santa's mission, just as Pitch and his Nightmares pose a challenge to MiM's utopia. Santa learns of children's wishes through letters; their hopes and dreams travel to MiM by helium balloons. The author-artist makes brief reference to the Man in the Moon's team of helpers on "the little green and blue planet" (the other Guardians, who will get their own spotlight in upcoming books). When MiM comes up with a solution to children's nighttime fears, he enlists the aid of the Moon's minions and his team of earthling Guardians (in addition to Santa, the Tooth Fairy, the Easter Bunny, the Sandman, etc.). What happens to Pitch and Nightlight remains to be explored in subsequent episodes, but this first adventure offers a visual feast and a complete mythology of the Man in the Moon, and his mission to dispel the nightmares of the children on earth.