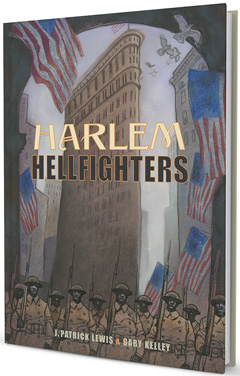

Harlem Hellfighters

by J. Patrick Lewis, illus. by Gary Kelley

The team behind And the Soldiers Sang delves deeply into another chapter of World War I--which began 100 years ago this month--with this beautiful and bittersweet tribute to the Harlem Hellfighters.

The exquisitely designed, oversize volume opens with two-dozen portraits of the men in uniform, rendered in charcoal pencil and pastels. The impact of this double-page windowframe of faces--some happy, some sad, some contemplative--informs the entire book. These 2,000 men--who began as the 15th New York National Guard, were federalized as the 369th Infantry Regiment, and were nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters by the Germans "for their tenacity," J. Patrick Lewis writes--are no longer a number, but rather individuals, as lifelike as the 24 men in those portraits. They were as talented with their instruments--playing jazz, blues and ragtime, led by "Big Jim" Reese Europe--as they were skilled on the battlefield.

From the title page, Gary Kelley sets up the tension between the two charges of the men: making music and making war. We see one of the Harlem Hellfighters, viewed through a hole in a wall pocked by bullet holes, seated at a piano with a rifle slung over his right shoulder. Kelley reinforces this dichotomy on the page opposite Lewis's introduction: the message on an iconic poster of Uncle Sam ("I want you for the U.S. Army") is obscured by a young African American man, standing at attention and sporting a tie and suspenders, a hat covering his brow, holding a trombone in his right hand.

The book traces the journey from their recruitment in April 1916 through to Big Jim's tragic death in May 1919, and portrays the mood in the United States as latecomers to the Great War, the segregation in America and how it followed the soldiers overseas. Big Jim and his band used their music to recruit others and eventually were sent to train in Spartanburg, S.C. Lewis writes that they "soon asked themselves whether German bullets could be as fatal as the rifle eyes of Southern gentry, women--highborn or down-and-out--triggered to rage, ministers sold on buckshot salvation, and deputy sheriffs certain that black was not any color of the rainbow."

In one of the most powerful spreads, a soldier stands with his back to readers on the deck of the Pocahontas, ferrying them across the Atlantic to the war raging in Europe. "Somewhere in the mid-Atlantic fog of history, two dark ships passed in the night," reads the text. The soldier gazes at a four-part horizontal sequence on the right-hand page. Readers can barely make out the sail of a ship in the top panel, but the ship draws nearer with each subsequent panel, until we can discern faces, more than half a dozen men in iron collars joined by chains; it is the ghost of a ship making the Middle Passage.

This image foreshadows the men's first three months in France, assigned to menial labor--shoveling dams, building hospitals, laying rail lines and dredging the Saint-Nazaire port. But at the other extreme, Jim Europe's band would play for the well-to-do in Aix-les-Bains. "In this elite playground, the band served honey through a horn to war-weary doughboys on leave," Lewis writes. At last, in March 1918, when they're sent to fight, the men of the 369th are taught French, how to read maps, how to use weaponry. Kelley honors them with a gorgeous re-imagining of Eugene Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830), with a valiant woman holding the French flag high as the Harlem Hellfighters race into battle.

Aside from Jim Europe himself, the most astonishing individual in the book is Henry Johnson, a former porter who in May 1918 killed four enemy soldiers, routed 24 more, and saved the life of a comrade. He won the Croix de Guerre, and was the first American serviceman to earn it--black or white. Kelley honors him in a dozen panels arranged as a windowpane, in a build-up to the heroic fight, leaving no doubt as to how he earned the nickname "Black Death." Yet the next page marks a stark contrast between the men's reputation as heroes on the front and the horrors at home: two black men hang from a tree, as President Woodrow Wilson stands by, just watching.

Upon their homecoming in February 1919, the Harlem Hellfighters took to Fifth Avenue in New York City, playing music to salute an Allied victory. But it does not end there: Big Jim, leading his band the night before they were to play for a 56th anniversary celebration honoring Robert Gould Shaw's 54th Massachusetts Regiment (originally a troop of freed slaves who fought for the Union), died at the hands of his drummer. Kelley juxtaposes a horizontal image of a soldier saluting a bronze relief sculpture of the regiment with a cameo of the stately James Reese Europe.

Kelley closes with a visual bookend featuring one of the young Hellfighters, in uniform and black mourning armband, holding a trombone in his right hand. "Three days later,/ the first black man ever to be given/ a public funeral in the city of New York/ rolled through the streets of Harlem/ past a delirium of mourners," Lewis writes. "In black armbands, the Hellfighters/ marched last, their hushed instruments/ at their sides."

This powerful image of the Harlem Hellfighters, so recently seen as vital contributors to the Allied victory, and then made mute in their sadness, all too accurately mirrors the men's experiences throughout the Great War. --Jennifer M. Brown