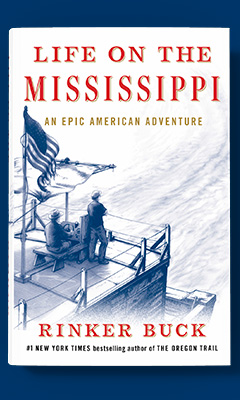

Life on the Mississippi: An Epic American Adventure

by Rinker Buck

For Rinker Buck, conquering the 2,000 miles of river between Pittsburgh and New Orleans on a hand-built wooden flatboat was more than an attempt to sate his lifelong appetite for adventure; it was a journey into the past, a way of exploring an overlooked but crucial chapter of American history. In Life on the Mississippi, his illuminative and entertaining account of his days aboard his ramshackle rivercraft, Buck describes how his fascination with "a primitive technology, a simple wooden box called a flatboat" deepened and transformed his understanding of his country and its past.

This feat--retracing a fabled route that doubles as an opening into a forgotten or misunderstood aspect of American history--is hardly the author's first. As teenagers, Buck and his brother completed a daring coast-to-coast flight across the U.S., becoming the youngest pilots to do so. The story became the stuff of legend, immortalized in his Flight of Passage, a cult favorite among aviators. Decades later, accompanied by another brother and a team of mules, Buck drove a covered wagon 2,000 miles along one of the nation's most arduous routes, the basis for his PEN/New England Award-winning book The Oregon Trail.

It was while researching the Oregon Trail pioneers that the author was first struck by the importance of "the great flatboat era," the period preceding and overlapping the westward push across the plains. The flatboat pilots of the eastern riverways had forged a "plucky, hand-me-down ingenuity"; that the flatboat has not enjoyed the same iconographic status as the covered wagon is a mistake Life on the Mississippi aims to address.

The reasons for the craft's marginalization in history, Buck suggests, are twofold. First, the lofty outlook of many traditional historians, with their "composite of high theory and 'great man' narratives," does little to reflect the "hardscrabble, edgy lives of most 19th-century Americans," of which the flatboat was a product. Secondly, few traces of the flatboat era have survived in the physical culture of the United States, which points to both the vessel's versatility and the resourcefulness of its operators. In one of the book's many revelatory details, Buck notes that most flatboats, upon reaching their destination, were stripped and sold as salvage, helping build the young nation's (largely wooden) infrastructure and boosting the boatman's profits. "History," Buck remarks, "was literally destroying a record of itself every time a flatboat landed and was taken apart to build something else."

Enthralled by the "chaotic, democratic forces that had contributed to the flatboat era," Buck is not content to simply study this history from afar; he closes the gulf of time by building a boat of his own. Though the resultant vessel is certainly flawed--the craftsmanship of the historical reenactor-cum-boatbuilder he hires to help leaves something to be desired--its charm is undeniable, its imperfections evocative of the rough-hewn texture of frontier life. Buck christens the flatboat Patience, a name that reflects his own temperament and, he soon learns, a requisite virtue of any halfway decent riverboat pilot.

Life on the Mississippi succeeds, in one way among many, as an ode to cool heads; life aboard the Patience puts the author up against the crowded and potentially hazardous industrial spaces that are the modern American riverways, requiring him to navigate around massive commercial tugboats as well as reckless pleasure boat owners. Family, friends and skeptical strangers repeatedly warn Buck that his river adventure will be the death of him, but his easygoing confidence and calm rationality win out. In fact, moments of stress and adversity often deliver Buck to a state of paradoxical serenity, and make for some of the book's most arresting scenes; when he successfully frees the stranded Patience from a mudbank, he is "filled with the most glorious feelings of freedom and self-love."

Along the way, Buck takes care to pay tribute to his many forebears in the genre of riverboat travelogue and cites the wisdom of these texts so frequently that their authors feel like crewmates. Asbury C. Jaquess's 1834 narrative and others like it provide an aesthetic as well as practical template for the Patience expedition, stoking Buck's sense of romance and getting him out of a few tight spots along the way.

More than once during his riverine odyssey, Buck recalls a passage from Jaquess's journal where the adventurer remarks that time spent sailing is among the best ways one might "acquire a knowledge of human nature." The significance of this notion is clear in Life on the Mississippi. Perhaps the book's most poignant aspect is achieved thanks to the author's ability to sketch brief, affecting portraits of the people with whom his voyage brings him into contact. Notable among these is the "river rat" Ron Richardson, whose brief appearance in the book has an outsized resonance. The story of Richardson's family and its multiple generations who lived in close connection to the river allow Buck, in a few short pages, to gesture at a whole world with America's rivers at its center. Buck's ability to deftly balance the intimate and the epic, along with his pervading charm and literary panache, make Life on the Mississippi an entertaining and engrossing read. --Theo Henderson

_Dan_Corjulo.jpg)