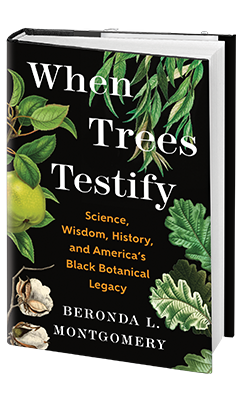

When Trees Testify: Science, Wisdom, History, and America's Black Botanical Legacy

by Beronda L. Montgomery

Beronda L. Montgomery (Lessons from Plants) weaves together personal narrative, family genealogy, American history, literature, and geography, along with her extensive knowledge of plant biology, in When Trees Testify, a profound and compelling exploration of Black botany and the many lessons trees can teach us about our past, present, and hoped-for future.

A plant biologist and self-described botanist, Montgomery traveled around the United States to visit (or revisit, in some cases) trees that feature in her memory and understanding of history. These visits provide the starting point in an exploration of what she calls "my reciprocal engagement with the essence of these living beings with whom I share space, history, and hopefully a future." There is the weeping willow tree on her aunt's property, where the low-hanging branches provided Montgomery a haven and secret hideaway as a child. And the "warm familial memories" of pecan trees, whose nuts flavored her grandparents' homemade butter pecan ice cream during the hot Arkansas summers of her girlhood. She describes her love-hate relationship with oak trees, recalling the work of collecting their fallen leaves each autumn alongside the joyful memories of bounding into leaf piles with her siblings.

Within these fond memories carried in the roots and branches of childhood trees, however, are darker truths of American history. Montgomery calls these trees "living witnesses to national history--and national shame," decisively connecting the violent history of slavery and racism in the United States to the present-day lack of representation of Black Americans in plant sciences. "Plants and African Americans are inseparable in American history," but based on the violence and trauma of those interactions, "many Black people in America rightfully have contentious relationships with plants and agricultural land... a somewhat prevalent and deep-rooted disenchantment with farming and other botanical endeavors."

Encouraging a naming and owning of this past, Montgomery works to connect various tree varieties to their nuanced histories. She recalls relatives teaching her and her cousins about which pecans would open easily, and why, noting too that scientists later felt the need to experiment to prove these hypotheses--discrediting the validity of Indigenous and intergenerational wisdom. Majestic runways of mulberry trees, such as those at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, are historically linked to failed attempts by early colonists to establish a silk industry in America--an industry dependent on the labor of enslaved children to be profitable. In the presence of the more than 600-year-old McLeod Oak at a plantation site in South Carolina, Montgomery reflects on the centuries of enslaved ancestors the tree watched work the nearby cotton fields.

And then there is America's legacy of lynching, violence that inextricably links trees to innumerable murders of, and threats against, Black Americans. Montgomery recalls a homecoming memory of a noose on display at her Arkansas public high school; the history of Billie Holiday's 1939 "divisive political song, 'Strange Fruit' "; and the frequent cultivation of poplar trees across Southern plantations, including Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest planted in Lynchburg, Va.--a place name impossible to disconnect from the ugly history of lynchings across the 19th and 20th centuries.

Montgomery does not shy away from the "both/and" that the natural world offers in spades. She revels in the beauty of cotton plants while honoring the back-breaking harm the crop played in the lives of her ancestors, even as recently as her parents' generation. Despite being the "first and only" Black person, Black professor, Black woman in many academic spaces throughout her career, she views herself as a "multigenerational cultivator of plants and holder of botanical expertise." And while she is a pioneer in these spaces, "being a pioneer is overrated. It generally speaks to progress denied, delayed, or unrecognized." She draws on historical documents to substantiate her inner knowledge of the wisdom and experience of those who came before her; in addition to recalling that her mother is better at sustaining houseplants than she is, she carries forward the legacy of Fred Montgomery, an ancestor born in 1835 Mississippi, most likely into slavery, and remembered to history only as a "married farmer."

This willingness to not only step into nuance but stay in it moves When Trees Testify into something deeper and more reflective than it first appears. As a plant biologist, Montgomery offers remarkable insights into trees of many varieties; as a complex, multi-layered person, she brings into this science a sense of self rooted in the past, grounded in the present, and looking forward to a vision of an America moving ever further from its violent past. Beautifully crafted and packed with observations sure to appeal to both plant and history enthusiasts, When Trees Testify is itself a testament to the strength, resilience, and wisdom of both the natural world and what might be possible when we bring the lessons of nature and history together in exploring Black botanical legacies in 21st-century America. --Kerry McHugh