I Kiss Your Hands Many Times

by Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

Some revelations have the power to change a life. In Marianne Szegedy-Maszák's touching memoir of her parents, I Kiss Your Hands Many Times, the secrets the author unlocks when she translates her deceased parents' love letters from Hungarian to English recast her family in a new light. While her parents' immigration from Hungary after World War II and Jewish mother's refugee status during the war were no secret, the fraught and intricate love story told in the love letters is one that was never recounted to the author when she was growing up.

Delving into family papers after her parents' deaths, Szegedy-Maszák discovers that her withdrawn and depressed father, Aládar, once possessed the initiative to court her mother, Hanna Kornfeld, against all odds--and drew upon the same reserves of courage when he used his diplomatic position to vocally oppose the Nazi regime, an act that led to his imprisonment in Dachau. Meanwhile, her mother, who always seemed conventional as a parent, was of the mettle to inspire and preserve a love that lasted through war and Nazi concentration camps. The impact of these revelations compelled Szegedy-Maszák to further research and explore her family's past. Her quest took her into the pitiless fray of World War II history, and to a world stage where events of unthinkable horror were unfolding. Amid these events of international tragedy, the author's family played a prominent role--her father with his anti-Nazi politics, and her mother's family with their dearly bought escape from the fate that befell most Hungarian Jews.

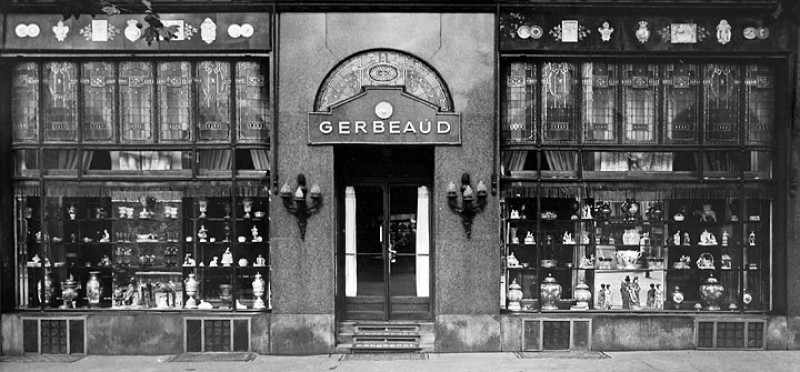

From its inception in 1940, the romance between Aládar and Hanna seemed star-crossed. He was a diplomat in a time when anti-Semitic sentiments were at their height and, moreover, was responsible not only for himself, but for the financial welfare of his family as well. For Aládar to be seen in a relationship with a Jewish woman could have jeopardized his political career as Foreign Minister. In addition, his career precluded any real courtship. Szegedy-Maszák writes about the limitations on their romantic opportunities in a manner that also vividly paints a picture of wartime Hungary: "He could not invite Hanna for dinner at the Grille, or to the movies to see The Wizard of Oz, or to the Circus, where a famous lion tamer named Togarek made women swoon and lions obediently cower. They could not meet for a coffee at the famous patisserie Gerbeaud."

Instead, the lovers saw each other most often at Ireg, the idyllic country estate of the Kornfeld family. It is particularly in her descriptions of Ireg, with its acres of land and graceful furnishings, that the author conveys bittersweet nostalgia for a vanished world. As descendants of the industrial titan Manfred Weiss, the Kornfelds lived as aristocrats--a fact that was to save their lives when the time came to escape Hungary, but also meant that the war changed their lives in uncountable ways. The serene beauty of Ireg, and the refuge it provided for Hanna and Aládar, stands in stark contrast to the postwar reality of life in exile. The priceless works of art owned by members of Hanna's family were pillaged in the war, and are on display to this day in an art museum. It would be justifiable for the author to feel outrage, yet the tone of gentle sorrow never wavers or turns to anger. Szegedy-Maszák also generously extends her grief for what is lost beyond the tragedy of her family to encompass all of Hungary, despite the pervasive anti-Semitism that almost certainly made the Nazis' mission of extermination easier. (Hungary is notorious for the thoroughness of its genocide during World War II.) For Szegedy-Maszák, perhaps the greatest loss is of the man her father might have been if not for his perceived political failures and hellish imprisonment in Dachau.

Though it is the story of a family, the author applies her skills as a journalist to researching the historical context of the time, so that I Kiss Your Hands Many Times is also the story of Hungary. The juxtaposition of the historical and personal is necessary in a story like this, as it conveys the sheer magnitude of the forces arrayed against the protagonists and their loved ones. Even the bond between Aládar and his needy sister, Lilly, is shattered by political forces, when she is jailed at least partly as a result of his activism abroad. The encounter between the historic and the personal is most viscerally embodied in a meeting between Aládar and Adolf Hitler.

What is most remarkable about the love story of Aládar and Hanna is not so much in the obstacles at its beginning--his political career and her Jewish roots--as the way their love triumphed over so many years of trauma and separation. The book is animated by the author's excitement in discovering the power of that love and its endurance through so many hardships, and even until death. --Ilana Teitelbaum

How did the research change the way you think of your parents?

How did the research change the way you think of your parents? Is there something specific you would like Americans to understand about the experience of Hungary in World War II?

Is there something specific you would like Americans to understand about the experience of Hungary in World War II?