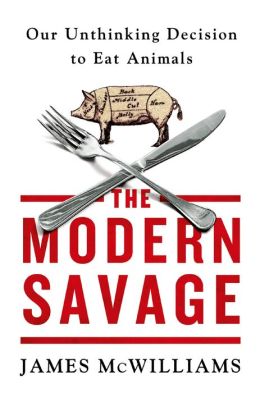

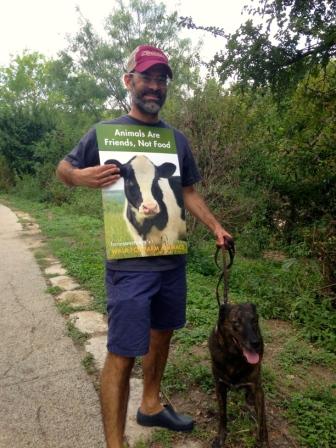

James McWilliams is a historian, professor at Texas State University and the author of Just Food: Where Locavores Get It Wrong and How We Can Truly Eat Responsibly (Little, Brown) and A Revolution in Eating: How the Quest for Food Shaped America (Columbia University Press). His new book is Modern Savage: Our Unthinking Decision to Eat Animals (Thomas Dunne Books; reviewed below). He contributes to many publications, including the Paris Review, the New York Times and Harper's.

James McWilliams is a historian, professor at Texas State University and the author of Just Food: Where Locavores Get It Wrong and How We Can Truly Eat Responsibly (Little, Brown) and A Revolution in Eating: How the Quest for Food Shaped America (Columbia University Press). His new book is Modern Savage: Our Unthinking Decision to Eat Animals (Thomas Dunne Books; reviewed below). He contributes to many publications, including the Paris Review, the New York Times and Harper's.

In the conclusion of The Modern Savage, you state, "Most ethically inclined consumers [will be persuaded by] 'the data of experience'... hard information that, as it accumulates, appeals to common sense...." Do you think most people need a personal experience of animal suffering to change their eating habits? Why do you think we often struggle to make decisions based purely on principle, rather than on self-interest?

Disembodied principles--by which I mean, principles not grounded in personal experience--are less powerful moral guides due to their abstraction from the ebb and flow of daily life. When it comes to animals and animal products, modern agriculture does a remarkable job of reinforcing this abstraction through what the anthropologist Timothy Pachirat calls "the politics of sight." Not only are we not allowed to see precisely how the sausage is made, but we're subjected to grossly fabricated narratives aimed to convince us that the animals we're eating did not suffer, led a good life and were killed lovingly. The more these narratives sink in, the harder it becomes for our principles to break through the rhetorical fog and shake our conscience back to the hard reality of slaughter and suffering. The harder it becomes, in other words, for our principles to merge with experience.

You propose we should value a creature's life based on the ability to feel, perceive or experience subjectively: "the claim that animals, like us, are living creatures that have an immense capacity to suffer--has been left off the table while the animals we claim to care so much about remain very much on it." Why do you think the pet industry is a multibillion-dollar business, yet we are willing to eat cows, pigs or chickens?

I'd actually argue that companion animals are commoditized and, to an extent, not seen as fundamentally different from animals in conventional agriculture. Pet breeding is [an industry that] obscures victims who are even less visible than the billions of farm animals reared for food. About three million potential pets are "euthanized" every year. They live horrible lives of great suffering. They never find homes because breeders reduce demand for them. It's a tragedy. That said, what's instructive is the contradiction between how we treat companion animals (the ones that find an "owner") and how we treat farm animals. One kind of animal we love and the other we eat. To my knowledge, there's no consistent moral justification for this double standard. Perhaps one reason we don't address it is that, on some level, we fear the conclusion that we'll reach and the consequences it will entail: not eating sentient animals. Humans can live with a lot of cognitive dissonance when the pleasure of the palate is at stake.

You state: "I'm not writing as a vegan zealot delivering a sermon from on high." Why do you hope to avoid this characterization?

Honestly, and I'll probably be vilified for saying this, but purity vegans who preach an uncompromising message drive me nuts. The tone of self-righteousness that permeates a lot of vegan discourse is more than off-putting. It's counter-productive. Too often, vegans forget that they were once non-vegans. They forget that we have inherited a culture in which eating animals is perceived to be as natural as breathing air and that, as a result, it's not as simple as declaring it wrong to eat animals and expecting people to go "oh, right, okay, I'll now stop eating animals." To seek change, you have to lead by charismatic example; you have to persuade with love; you have to accept gradual progress; you need patience; you have to not be an a**hole. Vegan zealots delivering sermons from on high aren't very good at these things. I simply want my readers to know that, in condemning the consumption of animals, I'm not condemning the people who eat animals. We are human, and we have limited moral resources. I just want some of those resources to be spent on this basic behavior that we rarely take time to morally evaluate. But I don't want to be seen as jerk because nobody listens to jerks and I want to be listened to.

You assert that the food reform movement is not only ineffective and intellectually dishonest, but may exacerbate the problem since 99% of the animals consumed derive from industrial sources, and non-industrial farms support the behavior that makes CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations) possible. You take three prominent food writers to task--Michael Pollan, Jonathan Safran Foer and Mark Bittman. How do you hope The Modern Savage will persuade them to rethink their loyalty to their carnivorous readers?

You assert that the food reform movement is not only ineffective and intellectually dishonest, but may exacerbate the problem since 99% of the animals consumed derive from industrial sources, and non-industrial farms support the behavior that makes CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations) possible. You take three prominent food writers to task--Michael Pollan, Jonathan Safran Foer and Mark Bittman. How do you hope The Modern Savage will persuade them to rethink their loyalty to their carnivorous readers?

These are super-smart guys. My only hope is that, as the food movement evolves, we will have a serious discussion about animal ethics. I'm not even saying veganism has to be the law of the land for the movement to be just. I just want to have the discussion. What's remarkable to me is that the food movement purports to examine every link in the food chain, except slaughter. What about the ethics of slaughter? What about the ethics of slaughter when you claim to care and even love the animal you kill? What's ironic here is that there are serious philosophical justifications that have been put forth to support the consumption of animals. I'm not saying these justifications are even remotely as convincing as the philosophical arguments against eating animals. I'm just saying there's material out there to initiate and frame a serious debate--material that goes well beyond the transformative work of Peter Singer. Typically, though, the leaders of the food movement will say things like "well, death is [only] one day" and leave it at that. That's lame.

You conclude that "[people] do not want to be conquered by logic or ideology so much as provided realistic options to explore through the exercise of free will." Why do you believe most people do not want both?

I don't dismiss the idea of moral logic and free will working together. It's just that they rarely do. One should be wary about making sweeping assessments about human behavior, but--when it comes to eating animals, at least--I've observed that humans place a premium on choice. Consumers (especially in the United States) are instinctively opposed to having their decisions aggressively shaped by external entities, especially governments. We're leery of the "nanny state." So when there's a significant ethical question at the core of a common behavior, consumers do not want to be bullied into making what someone else insists is the right choice. They want to come to their own conclusions on their own terms. Without getting too Chomsky-ish about it, this overestimation of our right to free will is one of the more insidious accomplishments of consumer capitalism, which has a way of instilling the perception of choice while directing our desires into increasingly narrow and amoral channels. We murder animals to eat them. Why should that choice be left to free will? Well, many think it should be. That's a persistent reality that, when it comes to my activism, I have no choice but to admit. All this said, I'm well aware that my book is sort of telling people what to do, even though I know they don't want to be told what to do.

The Modern Savage is very persuasive. For readers who decide to eliminate animal products from their diets, where should they begin? Do you have any favorite cookbooks or websites?

A lot of vegans say, "veganism is easy." It's not. There is no doubt that making the transition to a vegan (or even "veganish") diet--not to mention sticking to it--comes with challenges. A lot of people do it wrong, end up not feeling well, and revert back to the standard American diet, or however it was they ate beforehand. But others do it right and the personal consequences---not to mention the impact on the food system and the lives of animals---are incredible. Doing it right generally means eating whole foods, avoiding processed junk, getting B-12 from supplemented nutritional yeast or standard supplements, and eating as diversely as possible. I'm not a nutritionist, but I feel safe in saying that it's hard to go wrong when your diet is a fine balance of many different fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and whole grains. My own transition was buttressed and sustained by nothing more than access to a decent grocery store, a nearby vegan restaurant for inspiration, a community of supportive vegans and vegetarians, and knowledge of educational resources such as relevant cookbooks and vegan dietitian websites. For me, I find Mark Bittman's How to Cook Everything Vegetarian to be like a culinary bible and the websites of Jack Norris and Ginny Messina---vegan nutritionists/dieticians--to be chock full of soberly and judiciously presented information. --Kristen Galles, blogger at Book Club Classics

James McWilliams: Ethical Eating

You assert that the food reform movement is not only ineffective and intellectually dishonest, but may exacerbate the problem since 99% of the animals consumed derive from industrial sources, and non-industrial farms support the behavior that makes CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations) possible. You take three prominent food writers to task--Michael Pollan, Jonathan Safran Foer and Mark Bittman. How do you hope The Modern Savage will persuade them to rethink their loyalty to their carnivorous readers?

You assert that the food reform movement is not only ineffective and intellectually dishonest, but may exacerbate the problem since 99% of the animals consumed derive from industrial sources, and non-industrial farms support the behavior that makes CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations) possible. You take three prominent food writers to task--Michael Pollan, Jonathan Safran Foer and Mark Bittman. How do you hope The Modern Savage will persuade them to rethink their loyalty to their carnivorous readers?