|

| photo: Joe Henson |

Isabel Wilkerson won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing in 1994 for her work as Chicago bureau chief for the New York Times, and was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2016. Her first book, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction, among many other awards. She has taught at Princeton, Emory and Boston Universities and has lectured widely. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents will be published by Random House on August 11.

You very naturally and quickly inserted material related to the pandemic in this book. How do you handle that kind of lightness on your toes?

This book is so far-ranging: three continents, three cultures, the manifestations of the artificial hierarchies that caused so much tragedy in all three. The breadth and the scope of the research was just overwhelming. To build this story meant going into so many different aspects of life, to show how it affects all of us to one degree or another as we find ourselves entrapped in a caste system that we did not ask to be in. I was constantly adding, down to the wire. And then Covid-19 became an ever-present reality in the lives of Americans, and I had to figure out where it could go. It's been an extraordinary experience, just from a publishing standpoint, to have everyone working on this book spread out all over, trying to put together something this complicated, in addition to all the other projects that anyone who was working on this book was doing. It's a miracle. That it could come together at all is a testament to what can happen when people are dedicated and committed.

What's interesting is that it was already in there, because the book opens with a pathogen, and that was just a prescient--almost a premonition. There's something about how the mind works and intuition acts. A thesis of the book is that caste is so ever-present, an invisible powerful force in society and in all of our lives, that anything that happens somehow has a connection to caste.

This book involves such rich use of metaphor, in a serious piece of heavily researched nonfiction.

I think in metaphor. I'm primarily a narrative writer; narrative nonfiction is where I'm happiest, is the natural expression of my ideas. I find that I'm most at home in telling a story, and a metaphor is a story. It's making that connection, it's a way of reaching a reader through the most natural means that I know. I don't know of any other way.

American caste is both a novel concept and an instantly recognizable one. How does this book tread new ground?

The Warmth of Other Suns is the story of six million African Americans fleeing the Jim Crow South for the north and west over the course of much of the 20th century. Some would describe that as the story of a response to what many people would call racism. However, that word does not appear in Warmth, not in the text. It might be in the title of an article that I refer to--that book has 100 pages of notes--but that's not a term I use, because I don't think that it's sufficient to describe the phenomenon that undergirds interactions and structures of power in the United States. That doesn't mean racism does not exist, but I did not feel that it was the most applicable or accurate way to describe what people were fleeing, or what they met in the places that they fled to.

This book is a continuation of the perspective I took with Warmth. I think that using the word caste requires us as Americans to think differently. It automatically expands our sense of what we think we know. It's an uncommon word to apply to ourselves, so it gets you thinking in a way that words we're accustomed to using can blur. Because it's not a word that we're accustomed to using, it's not judgmental, doesn’t feel as if it's an accusation, doesn't automatically incite shame or blame or guilt. Not only is it accurate, but it is a portal to understanding. That's how I connect with the word as a writer.

.jpg) Historically speaking, caste has on occasion been applied to the United States. Charles Sumner had used the word; Martin Luther King had used the word. Where people have looked deeply at the structures that we have inherited throughout American history, they have often come back to this word. But there's been nothing that dives deeply into what that actually means. This was an attempt to do that, and to go to the original caste system that would come to mind most readily, which would be India, and that of the short-lived, terrifying Third Reich, and the interconnectedness of those two and that of our own country.

Historically speaking, caste has on occasion been applied to the United States. Charles Sumner had used the word; Martin Luther King had used the word. Where people have looked deeply at the structures that we have inherited throughout American history, they have often come back to this word. But there's been nothing that dives deeply into what that actually means. This was an attempt to do that, and to go to the original caste system that would come to mind most readily, which would be India, and that of the short-lived, terrifying Third Reich, and the interconnectedness of those two and that of our own country.

Then there are the pillars, which I came to as a result of going deeply into the topic: what had been written before; the Laws of Manu, which is the code for the Indian caste system; the Nuremburg Laws; and, of course, the aspect of all this that I knew best, the Jim Crow laws in our own country. I researched them ever more deeply in order to emerge with what I have described as the eight pillars of caste.

I read scores of books from multiple cultures. I collated and pulled together the histories and the ways of enforcing these caste systems into a more easily digestible rendering in one place.

At what point did you see the book take shape?

This has been simmering within me for a long time. Warmth was a precursor. It's about the Great Migration, but it's really about freedom and how far people are willing to go to achieve it, and the caste system that they were forced to flee. That's one reason why Warmth has remained so constant a presence in all the ups and downs we've seen since it came out. There's still been a hunger for it that defies the presumed topics, because the topic is so much bigger than the Migration itself.

I heard a side note on the news about anthrax emerging from the permafrost in Siberia in July of 2016. I didn't know what I might do, but I knew it was something. That was the beginning of this book. Who knew that by the time I would complete it, we would be in a global pandemic that would shut down humanity in its tracks. I didn't know at that moment I would write a book about caste, but that was the beginning of an understanding that this was big. The planet was in peril, humanity was in peril, and this was a seemingly small example that didn't get a lot of attention at the time, but it spoke to me strongly. Every passing month, every passing year after that, it became more urgent. It was a progression toward this book.

First the pandemic, and then the responses to George Floyd's murder, mark this book's entry to the world. It feels very timely, but also timeless.

Whenever I write, I seek to be timeless, and focus on the history. We keep seeing the repeat of the history that we're not paying attention to or don't know well enough. These events are shocking, but not surprising if you know the country's history. I go back to one of the many metaphors in the book, the old house: I'm essentially coming in as the inspector of the building and saying, these are the weak points that need attention. If you know your house, then you know what is wrong with it and you will seek to fix those things. If you don't know, you can't fix them. If you have no interest in knowing, you absolutely are not going to be able to fix those things.

Without transcending the artificial boundaries between us, without seeing the humanity in one another, we will continue to hurt each other. What we've seen recently has been brewing and simmering for 400 years. It rises and it falls, accelerates and slows, but it always comes back, because we're not dealing with the essential structures that have created the system we live in. Until those systems are addressed, it will continue. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Eleven book industry associations have launched the Book Industry Health Insurance Partnership (BIHIP), an alliance with Lighthouse Insurance Group (LIG) Solutions that is designed to provide members of the associations a choice of health insurance options. These include ACA-compliant major medical, Medicare/supplements, short term policies, vision, dental, critical care and supplemental coverage, as well as small group/Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs).

Eleven book industry associations have launched the Book Industry Health Insurance Partnership (BIHIP), an alliance with Lighthouse Insurance Group (LIG) Solutions that is designed to provide members of the associations a choice of health insurance options. These include ACA-compliant major medical, Medicare/supplements, short term policies, vision, dental, critical care and supplemental coverage, as well as small group/Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs).

Tomorrow Barnes & Noble is

Tomorrow Barnes & Noble is  The new B&N will require everyone to wear face masks and maintain six feet of social distancing. Staff will have regular temperature checks. Registers have protective barriers, and the store is offering curbside and pick-up service.

The new B&N will require everyone to wear face masks and maintain six feet of social distancing. Staff will have regular temperature checks. Registers have protective barriers, and the store is offering curbside and pick-up service.

"Amid all the gloom and uncertainty, opportunity knocked," she said. "We were offered a beautiful larger location for the same rent. The result is fabulous. I continue to think bookstores are a coveted tenant for landlords. Use this to your advantage during this time. Our customers are so supportive and the feeling of localism has never been stronger. I wish us all success in these very tough times."

"Amid all the gloom and uncertainty, opportunity knocked," she said. "We were offered a beautiful larger location for the same rent. The result is fabulous. I continue to think bookstores are a coveted tenant for landlords. Use this to your advantage during this time. Our customers are so supportive and the feeling of localism has never been stronger. I wish us all success in these very tough times."

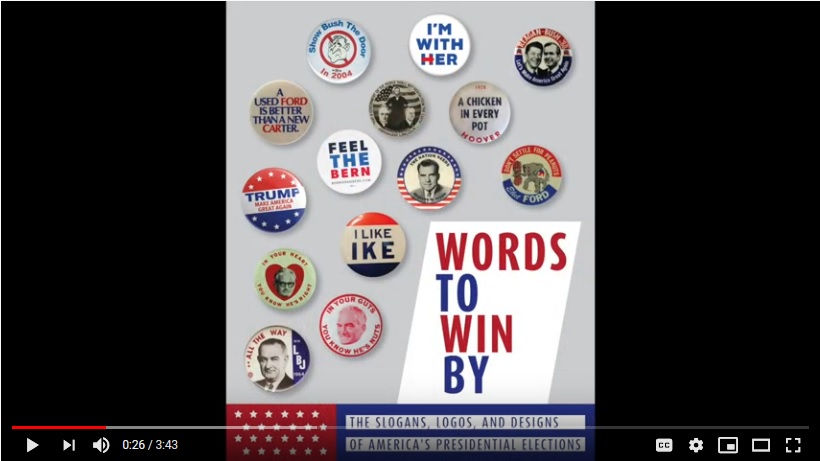

Words to Win By: The Slogans, Logos, and Designs of America's Presidential Elections

Words to Win By: The Slogans, Logos, and Designs of America's Presidential Elections

.jpg) Historically speaking, caste has on occasion been applied to the United States. Charles Sumner had used the word; Martin Luther King had used the word. Where people have looked deeply at the structures that we have inherited throughout American history, they have often come back to this word. But there's been nothing that dives deeply into what that actually means. This was an attempt to do that, and to go to the original caste system that would come to mind most readily, which would be India, and that of the short-lived, terrifying Third Reich, and the interconnectedness of those two and that of our own country.

Historically speaking, caste has on occasion been applied to the United States. Charles Sumner had used the word; Martin Luther King had used the word. Where people have looked deeply at the structures that we have inherited throughout American history, they have often come back to this word. But there's been nothing that dives deeply into what that actually means. This was an attempt to do that, and to go to the original caste system that would come to mind most readily, which would be India, and that of the short-lived, terrifying Third Reich, and the interconnectedness of those two and that of our own country. Spring by Leila Rafei adeptly casts the Arab Spring uprising as a backdrop for upheaval in the lives of three ordinary people in her extraordinary debut novel.

Spring by Leila Rafei adeptly casts the Arab Spring uprising as a backdrop for upheaval in the lives of three ordinary people in her extraordinary debut novel.