_Martha_Schickler.jpeg) |

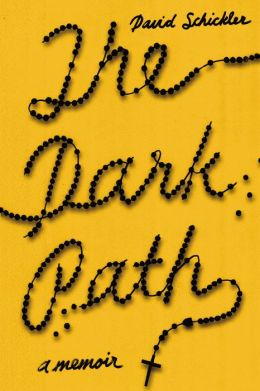

| photo: Martha Schickler |

David Schickler is the author of the linked story collection Kissing in Manhattan and the novel Sweet and Vicious. In those works he has proven an adept chronicler of modern life, its joys and corresponding sorrows, the places attraction can turn into obsession and how the intensity of relationships can turn from transformative to dangerous. These gifts for balancing dark and light are on wonderful display in Schickler's new memoir, The Dark Path (our review is below). In addition to Schickler's usual adept handling of earthly romantic entanglements, he shows that he can handle another intense relationship with equal skill--the pursuit of God--making the book sexy and profound in equal measures. Schickler is also the co-creator and executive producer of the new Cinemax series Banshee.

One of the central themes of The Dark Path is an idea you had from childhood, that God can be found in darkness and in the shadows just as easily as in more traditional places. What role has this idea/experience played in your life?

Like anyone else I've ever met in the world, I want to be loved. To be loved, you have to feel special, unique. To feel special, you sometimes need to feel that you are in on a secret. I never feel more keenly that I am in on a secret than when it is nighttime and I am alone somewhere with a woman, or else when I am in a dark or quiet church, and I close my eyes and pray to, or merely listen for, God. I prefer the dark to the light so often because I love intimacy (whether with the divine, or with former girlfriends, or now, with my wife) and intimacy can be so fragile. We think of light as something that can reveal truth, but sometimes it can wreck and ruin truth or chase it away by being too direct, too glaring, too eager to see everything at once rather than being suspensefully glad to see truth revealed one feature, one whisper, one unbuttoned button at a time.

I love truth, but I love excitement, too. And God and women and life are more exciting to me in the dark.

The priests you were drawn to in The Dark Path were Jesuits. Do you think their model of spirituality was an attraction for your own developing gifts and sense of self?

One joke about Jesuits is that they create atheists and other Jesuits. What I think that means is that Jesuits challenge you to know and be able to articulate and live out to their fullest natural consequences your feelings, intuitions and understandings about God and whether He exists and if He does, how He relates to you, personally, daily. Your beliefs about the divine make requirements on you and how you live, Jesuits might say. It is each person's job to realize that, to face it and to have an answer, Jesuits might say. You are shirking the most vital responsibility of living if you don't, Jesuits might say.

I was educated by Jesuits in high school and at Georgetown, and so I internalized that challenge of theirs very deeply. I came to feel that I had to scour the depths of my own heart and mind and life and I believed that doing so had both temporal and eternal consequences. This led me to discernments and discoveries about myself, but it also led me to put great (and definitely self-obsessed and maybe even un-Christian) pressure on myself to know, to quest, to understand, to apprehend truth as entirely as possible. This memoir is about a time in my life when doing all that exhausted me and broke me, and I had to learn a more patient way, a way that would leave room for unanswerable mystery, especially in my relationships with women.

The intensity of your relationship with Mara suffuses the whole book. You talk about trying to keep God and her "in fierce parallel." What does that phrase mean to you?

Prayer and sex were always the two things that called to me most deeply and they still are. But when I was in college, dating Mara, the different powers of those two forces (prayer and sex) were not something I had fully come to terms with yet, and so, out of fear, I thought of them as separate tracks inside me: fierce, parallel tracks. I feared that if the tracks ever crossed, the voltage of one would short out the other. I was thinking about both too rigidly, too clinically. Even the word "parallel" is a mathematical one, and it's wrong here, as is the idea of prayer or sex as a fixed track toward anything.

What they really both are, prayer and sex, are paths inside me, dark, winding, often inscrutable paths. They probe forward more than they lead forward (sort of like the best fiction does), and that is their nature, and I know and love that now, without fearing it.

You had a spiritual director betray your trust and behave in an inappropriate manner toward you. Do you think this hastened your leaving the Jesuit path? If this hadn't happened, do you think you still could have ended up a priest?

We can call it out: yep, a Catholic priest grabbed my ass one day, and yep, it was a big wake-up call, but not in the way you might expect. Rather than launching me on a life of fury toward the Catholic clergy (which many people who got far more taken advantage of than I did both feel and are justified in feeling), it just brought to great, immediate clarity for me the fact that women and the intimacies I'd shared with them were going to be in no uncertain terms shut down for me forever if I became a priest. There are many wonderful women in the Catholic church, but the priesthood is a boys' club, period. It is a club with a lot of magic and allure to it, but the best parts of the magic are practiced only by men.

The magic I felt and feel in the company of women is a kind I needed full access to. No amount of canon law was going to legislate out of my days and nights the laughter and skin and glorious mystery of women. So, while I'm not glad a priest grabbed my ass, I'm glad I had all the above brought powerfully home to me. Yes, maybe I could have been a Catholic priest if that incident hadn't happened. But I would likely have been an unhappy, half-human one, and the God I believe in would not have wanted that. There are excellent celibate priests in the Catholic church who have true vocations to celibacy. I wouldn't have been one of them.

Midway through The Dark Path you discover your gift for writing and the solace you find in others' stories. Do you think your book is as much about that discovery--the pull between art and faith--as it is about the balancing of flesh and faith?

Midway through The Dark Path you discover your gift for writing and the solace you find in others' stories. Do you think your book is as much about that discovery--the pull between art and faith--as it is about the balancing of flesh and faith?

Absolutely. The pull between art and faith remains the central drama or at least fascination inside me. On many days, I don't know how it is tenable for me to believe so deeply in Jesus Christ and simultaneously to need so deeply to laugh my ass off at Louis C.K.'s rawest routines or to have the sh*t scared out of me by The Shining or to write violent, sexy screenplays for my TV show Banshee. Tertullian allegedly said of Christianity, "I believe this because it is impossible." I feel the same way about it, and I feel that way about Breaking Bad and The Great Gatsby (the novel). Christ transgressed audaciously upon or elevated to glory the mundane: that's what great comedy, great fiction and great sex do, too. I'll spend the rest of my life wondering gladly how all those things can be simultaneously so.

There is a wonderful "warts and all" quality to your work. You are not afraid to show your missteps, of looking like an jerk or a dweeb. Did you ever wonder if you were going too far?

I am an easily bored reader of literature and lover of movies and television and art. It has always been the case for me that only stories that "go too far" (to borrow your phrase) hold any interest for me. I love Jesus Christ for going too far and Ron Burgundy in Anchorman for going too far and Mother Teresa for going too far and Kristen Wiig in her best SNL sketches for going too far.

Since I have never written a memoir, I don't know how other people go about it, but what I did was look back and try to recount almost exclusively the times when I or my life went too far: when my heart broke, when my body broke, when I laughed so hard I fell down, when my first lover and I found sexual ecstasy together, when God swept me off my feet, when my faith ended up in the gutter. That is the only way I know how to get to the truth.

I have spent my whole life almost mortally terrified of niceties and tepid social conventions: not genuine kindness or friendliness, mind you, but the kind of middling, how's-the-weather brand of conversations or interactions. Such things make me afraid that all the great hopes and fears and wonders and perversities in the human heart might get blotted out or glossed over via polite handshakes. I would rather come off as the world's greatest ass or dweeb or hero than bore people. It may be a serious sin of pride that I feel that way. But I know what kind of storytelling works for me.

My favorite Boston songwriter ever, Jonathan Richman, once wrote in his song "A Plea for Tenderness": "I don't want to hear about your stupid cats. Just talk about love or sex or starving hearts. Or just shut up, and I'll go." That pretty much sums up how I felt while I was writing this memoir, and how I feel much of the time, period. Bring on the love and sex and starving hearts!

What's the difference between being a "Saturday night writer" and a "Sunday morning writer?"

Being a "Saturday night writer" means, for me, that I'm attracted to the edgiest, most fringe elements and flavors of human nature because they are the ones that slap me awake and make me take notice and empathize and laugh and cry and sit bolt upright. I like big stakes and dire consequences. I am drawn to murder, orgasms, crazy unbridled laughter and soul-baring declarations of love (the things you might see in the movie you go to late on a Saturday night), because in moments like those, it is almost impossible for characters (and for us in the audience) to lie to one another. We are flush with truth and that jazzes me, and I think many people agree whether they confess it or not. In the song "Candy Everybody Wants," Natalie Merchant of 10,000 Maniacs wrote: "If lust and hate is the candy... if blood and love taste so sweet... then we give them what they want." Amen to that.

It is clearly the case that not every reader or TV/film viewer or patron of the arts agrees with me. Someone out there is writing gentler, spirit-calming stuff, the kind of thing you might associate more with a spiffy, proper Sunday morning. But I don't look to fiction or memoir or movies, etc., to have my spirit calmed. I can get that by praying or by (depending on the day) taking a walk or being with my wife or children or certain other family and friends. I write and read to shock myself away from self-deception about what I and humans in general are capable of. I don't think that that boils down to prurience: it is just what keeps writing and reading invigorating for me.

Looking back over your spiritual journey and your writing life, to what degree is "the dark path," the sense of God's presence in shadows and darkness, the same place you've got to enter to write good, lasting work?

I only enter a dark place when I write because I find the truth hides in dark places and I have to go there either to ferret it out or simply to gaze at it and report on what it's up to. As to the question of whether the truth I search for in the dark shadows is God or not depends upon the kind of writing I am doing.

When I wrote this memoir, I went particularly in search of God because this was and is the story of my Christian faith and the upheavals I've endured in pursuing that faith. I couldn't tell the story without plenty of whiskey and sex and violence and freaky side characters (i.e., things that might be considered dark) because those are simply things that are me or are things I can't help loving. In other words, there's a chance that the only reason in this memoir that I was so desperate to find God in the darkness is because I was in the darkness already and I wanted not to be alone there and so I hoped that God was in there with me.

But when I write fiction (books or screenplays) I don't enter a place where I purposefully find God or look for God or acknowledge God's presence. It is far too creepy and false to do that, and it will kill preemptively any chance the writing has of proceeding on its natural merits or shortcomings. When I write fictively I have to forget about God, at least consciously, the same way that I have to forget about God if I'm having sex, or trying to enjoy watching a movie or reading a novel. I just try to tell the truth in as original and entertaining a way as possible, and if God is in that truth, that is His doing and not mine. This may sound like a minor point, but to me it is vital. When I hear what is referred to as Christian rock and roll or read a fictional story that has some planned allegorical agenda to testify to Christian (or any other religious) dogma, I cannot run away fast enough. Others may derive great comfort or pleasure from such offerings, but to me they are insults to the imagination. --Donald Powell, freelance writer

David Schickler: The Pull Between Art and Faith

The scandalous bits will get the most press. Some surprised me, like colleges employing "hostesses" to squire high school recruits around campus, take them out to parties, then stay in touch until they commit, dazzling them with the carrot of a relationship. There's also academic fraud, rogue boosters, private planes, untraceable big money and third parties involved in recruiting and eligibility, especially in the "shadowy world of 7-on-7," the spring and summer touch football extravaganza of player evaluation. And the money! In the cathedral of college football, "there is just one church, one road leading in a single direction. To Austin and the University of Texas." The football program generated $103.8 million in revenue during the 2011-12 season, and $78 million in profit. Make no mistake: this is definitely not amateur hour.

The scandalous bits will get the most press. Some surprised me, like colleges employing "hostesses" to squire high school recruits around campus, take them out to parties, then stay in touch until they commit, dazzling them with the carrot of a relationship. There's also academic fraud, rogue boosters, private planes, untraceable big money and third parties involved in recruiting and eligibility, especially in the "shadowy world of 7-on-7," the spring and summer touch football extravaganza of player evaluation. And the money! In the cathedral of college football, "there is just one church, one road leading in a single direction. To Austin and the University of Texas." The football program generated $103.8 million in revenue during the 2011-12 season, and $78 million in profit. Make no mistake: this is definitely not amateur hour.

_Martha_Schickler.jpeg)

Midway through The Dark Path you discover your gift for writing and the solace you find in others' stories. Do you think your book is as much about that discovery--the pull between art and faith--as it is about the balancing of flesh and faith?

Midway through The Dark Path you discover your gift for writing and the solace you find in others' stories. Do you think your book is as much about that discovery--the pull between art and faith--as it is about the balancing of flesh and faith?