|

| photo: Ann Fox |

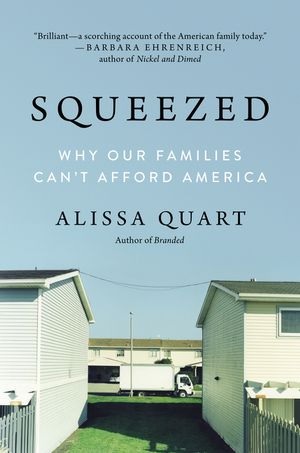

Alissa Quart (Branded

, The Republic of Outsiders), journalist, poet and executive editor of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, probes the crumbling foundation of the American Dream: an unstable middle class. In Squeezed: Why Our Families Can't Afford America

(Ecco, $27.99; reviewed below), Quart blends facts, interviews and analysis into a powerful, affecting portrait of a country--its tired, its poor... and its possibilities.

You use "Middle Precariat" to describe the status of many of the people whose stories you tell in Squeezed. Can you explain that term?

The word "precariat" was popularized seven or so years ago to describe a rapidly expanding working class with unstable, low-paid jobs. I coined the term "Middle Precariat" to describe those who should be comfortable or even bourgeois, but it hasn't worked out that way for them. These are nurses, librarians, professors, even lawyers who should be in the prime of their working lives, but some of whom can't afford to rent an apartment big enough for their families and are certainly priced out of buying their homes. They have less job security and they may not have reliable work hours. They certainly don't have pensions or adequate retirement funds. As I say in the book, the Silicon Valley-like calls for disruption may mean that even in later middle age, the Middle Precariat may have their positions "reimagined." That cruel euphemism means they are to be replaced by younger, cheaper workers and sometimes now--or eventually--by machines.

Talking to a mother who returned to school to pursue a new career, who blamed herself for her inability to provide opportunities for her daughter, you wrote: "It made me want to break my journalist role... to say, it's not just you." That thread runs throughout this book: it's not just you.

One of my impetuses for writing Squeezed was the wish to tell the people I was talking to that it was not their fault. That's real self-help, in my opinion--reassuring people (when it's true, that is) that they are suffering due to a system error rather than their own mistakes, bad choices or personal failings.

I'd sometimes share information with subjects, like data about schools, for instance, or simply remind them they are part of a broader societal failure: "It's not you--it's this country."

As you point out, "America seems not to care about care." You interview people who experienced their struggles in isolation even as they provided care for others, and often gender roles factored into that. How might we communicate better about gender roles with people unable to recognize the need for change?

The caregiving of mothers, babysitters and domestic workers and guardians is some of the worst paid and most professionally disdained work out there. Yet it is the most important. This is an outrage.

It's also very much the legacy of sexism and racism. It's the coda to a federal decision blocking domestic workers and farmworkers from labor law protections: the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 allowed private-sector employees to protest abusive working conditions or bargain collectively, but domestic workers were excluded, due to pressure from Southern lawmakers. The contempt and punishment of the emotional and physical labor of care is written into our very political code.

Still, how are we to understand the apparent contempt for care work and care workers in this country when we are also told that childhood is sanctified and romantic and motherhood is beautiful? I think we need to alter the way we position care work of any kind. One way is protecting female employees from a gender pay gap, as this discrepancy can have a lot to do with mothers taking a hit professionally after their children are born. But I also think fighting the stigma around care is a conceptual thing: we need to start to see care capacity as a moral and professional advantage rather than simply a vulnerability or a distraction from "real work." Easier said than done, of course.

You write about your own career beginnings, teaching in a community college, "hoping to start a 'career' in poetics, of all ridiculous ambitions." And now, you are indeed a poet. There's a line in your poem "Strong Copies" in Monetized--"Here's to reproduction: photography, Twitter, pregnancy."-- that ties deeply to themes in your reporting and in Squeezed. How do your different kinds of writing relate to each other?

You write about your own career beginnings, teaching in a community college, "hoping to start a 'career' in poetics, of all ridiculous ambitions." And now, you are indeed a poet. There's a line in your poem "Strong Copies" in Monetized--"Here's to reproduction: photography, Twitter, pregnancy."-- that ties deeply to themes in your reporting and in Squeezed. How do your different kinds of writing relate to each other?

I love this question because as a journalist, I've reported on, say, what happens to the people gentrified out of their cities or neighborhoods. I report on mothering, or social class or newspapers shutting down. And then these themes entered my poetry. Sometimes, I think of poetry as the afterbirth of my journalism.

My last poetry book, Monetized, has similar preoccupations as my nonfiction, like Squeezed or my first book, Branded: to monetize means to "convert into or express in the form of currency." It's a word everyone uses in the Silicon Valley when they speak of turning something into commodity. In journalism and, of course, in poetry, turning a labor of love or something in the name of the social good into something of monetary value can be hard or impossible. So Monetized is sort of an ironic title.

What books are on your nightstand?

The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner, George Orwell's Fighting in Spain, In a Day's Work by Bernice Yeung, the poetry collection Float by Anne Carson, Skating to Antarctica by Jenny Diski... basically it ranges from political reporting to poetical novels and memoirs to rigorous poetry. And you'll notice it's almost all by women. I hope I don't sound like a separatist, but most of the books I read are by women!

What are you working on now?

I am working on a collection of poetry that's quite formalist and political--lots of breaking news in it

about harassment, etc.--called

Thoughts and Prayers.

What's your hamster's name and why?

Tabitha. My daughter tells me it was a name she found "cheery." I think it came to her from Beatrix Potter's book about Tabitha the cat, which is paradoxical, of course, as cats eat hamsters.

I think she wanted a cat.

Alissa Quart: The American Squeeze

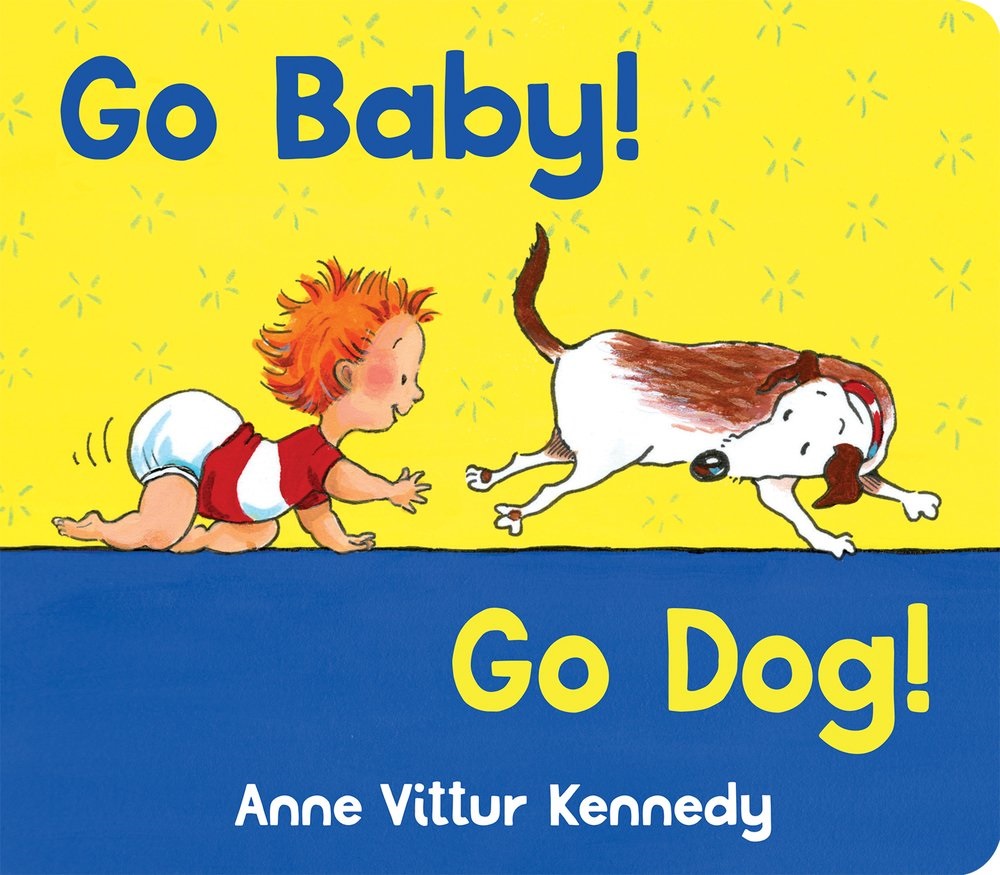

Go Baby! Go Dog! by Anne Vittur Kennedy (Whitman, $7.99, 20p., ages 1-3, 9780807529713)

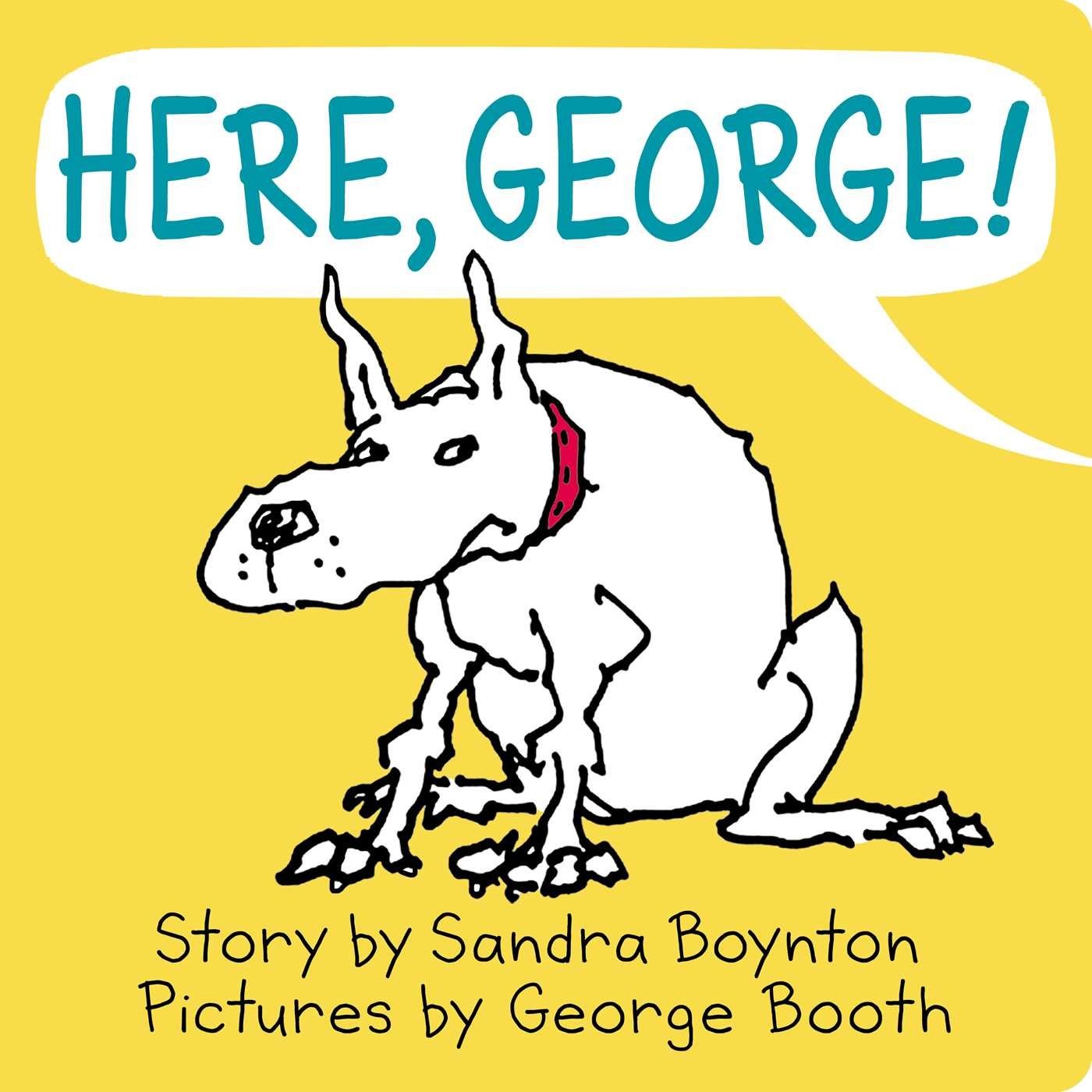

Go Baby! Go Dog! by Anne Vittur Kennedy (Whitman, $7.99, 20p., ages 1-3, 9780807529713) Here, George! by Sandra Boynton, illus. by George Booth (Little Simon, $7.99, 32p., ages 1-3, 9781534429642)

Here, George! by Sandra Boynton, illus. by George Booth (Little Simon, $7.99, 32p., ages 1-3, 9781534429642) Goodnight, Good Dog by Mary Lyn Ray, illus. by Rebecca Malone (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $8.99, 30p., ages 1-3, 9781328852427)

Goodnight, Good Dog by Mary Lyn Ray, illus. by Rebecca Malone (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $8.99, 30p., ages 1-3, 9781328852427) Baby Cakes by Theo Heras, illus. by Renné Benoit (Pajama Press, $13.95, 32p., ages 1-5, 9781772780307)

Baby Cakes by Theo Heras, illus. by Renné Benoit (Pajama Press, $13.95, 32p., ages 1-5, 9781772780307)

You write about your own career beginnings, teaching in a community college, "hoping to start a 'career' in poetics, of all ridiculous ambitions." And now, you are indeed a poet. There's a line in your poem "Strong Copies" in Monetized--"Here's to reproduction: photography, Twitter, pregnancy."-- that ties deeply to themes in your reporting and in Squeezed. How do your different kinds of writing relate to each other?

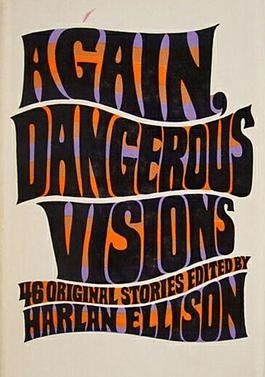

You write about your own career beginnings, teaching in a community college, "hoping to start a 'career' in poetics, of all ridiculous ambitions." And now, you are indeed a poet. There's a line in your poem "Strong Copies" in Monetized--"Here's to reproduction: photography, Twitter, pregnancy."-- that ties deeply to themes in your reporting and in Squeezed. How do your different kinds of writing relate to each other? Prolific and pugnacious science-fiction author Harlan Ellison died on June 28 at age 84. He was a major figure in the New Wave movement, known as much for his 1,700-plus stories, screenplays, essays and other writing as for his abrasive personality. Ellison won eight Hugo Awards, four Nebula Awards, five Bram Stoker Awards, two Edgar Awards and more, as well as a host of lifetime achievement awards; his list of feuds, lawsuits and alleged assaults is nearly as expansive. He was famously fired after one day at Disney when Roy O. Disney overheard him joking about a pornographic movie with Mickey Mouse. Ellison was also a supporter of the civil rights movement, an opponent of the Vietnam War and a ceaseless advocate for writers who he considered mistreated.

Prolific and pugnacious science-fiction author Harlan Ellison died on June 28 at age 84. He was a major figure in the New Wave movement, known as much for his 1,700-plus stories, screenplays, essays and other writing as for his abrasive personality. Ellison won eight Hugo Awards, four Nebula Awards, five Bram Stoker Awards, two Edgar Awards and more, as well as a host of lifetime achievement awards; his list of feuds, lawsuits and alleged assaults is nearly as expansive. He was famously fired after one day at Disney when Roy O. Disney overheard him joking about a pornographic movie with Mickey Mouse. Ellison was also a supporter of the civil rights movement, an opponent of the Vietnam War and a ceaseless advocate for writers who he considered mistreated.