|

| photo: Dana Kroos |

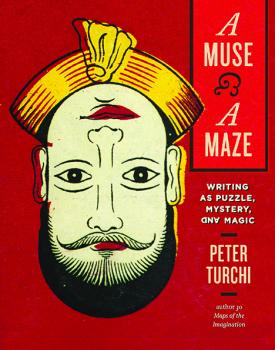

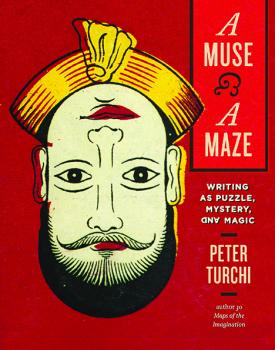

The editors of the New York Times Magazine called Peter Turchi's Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer (Trinity University Press) one of the best nonfiction books of all time. In it, he explored the intersections of the world of maps with the world of writing--how geography, physicality, and maps themselves can influence the work of a writer. In his new book, A Muse and a Maze: Writing as Puzzle, Mystery, and Magic (also from Trinity), Turchi exchanges maps for puzzles, comparing writing to puzzle solving and puzzle creating, and discusses what the differences between puzzles can show a writer facing the labyrinth of an unwritten work.

My high school librarian made photocopies for students of the daily newspaper's cryptoquip puzzle. I did them religiously, and I'm certain my reading informed the puzzling and vice versa. Where did the ideas in your book get their start?

The ideas must have gotten started at least as early as the day I read my first Encyclopedia Brown book as a boy (and then the Sherlock Holmes stories and Agatha Christie mysteries), which would have been around the same time I was introduced to jigsaw puzzles, word searches and the jumbled words in the daily paper (I didn't discover cryptoquips until much later--kudos to your high school librarian). I also did magic tricks and played a little chess. And I started writing at an early age. I didn't think about how those things--puzzles, games, magic, writing--were related until five or 10 years ago. Until then, I felt guilty about doing puzzles, as plenty of people consider them a waste of time. I decided to devote some thought to how and why different kinds of puzzles are intriguing. The actual writing got its start in the form of lectures I gave during residencies of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, N.C. It's the kind of graduate program where you can tell people that sudoku are relevant to fiction writing and they'll let you explain yourself. The ideas kept percolating, and as I translated the original lectures into essays I added and revised.

In addition to puzzles, you touch on magic and magicians. "Magician" can refer to a fantasy-world wizard or to the David Copperfield type of magic, where the practitioner uses slight-of-hand and deception to fool the audience. Which "magic" has more potency for writers?

In addition to puzzles, you touch on magic and magicians. "Magician" can refer to a fantasy-world wizard or to the David Copperfield type of magic, where the practitioner uses slight-of-hand and deception to fool the audience. Which "magic" has more potency for writers?

Just as some people have no time for puzzles, others reserve their scorn for magicians. But I'd suggest there isn't such an enormous difference in the sense of wonder we feel seeing a rabbit produced from an empty (we thought) hat; Citizen Kane (mere light and shadows on a screen); Van Gogh's Church at Auvers (thick paint on canvas); or the sense of wonder we feel reading, say, Bleak House (ink on paper) and believing not only that we've gotten a glimpse at an earlier London, but that we've spent time with a remarkably entertaining man named Charles Dickens. "Deception" has negative connotations, but writing poetry and fiction, like doing magic, is all about the strategic presentation of information, about enchantment and transcendence.

What sorts of things were the most formative for you as a writer? Did you come to maps/puzzles later in life?

As is true for a lot of writers, books and stories were important to me early. The books our mother read to my sister and me and the first books I checked out of the Baltimore County Public Library might not have qualified as literature in anyone's eyes, but they gave me an early sense of the power of narrative, the delights and surprises fiction and poetry can provide. Our father was not a reader--not that he was illiterate, but I don't remember him ever reading a book for pleasure--but he was a storyteller. He was the sort of storyteller who liked to revisit his greatest hits, like the time he and his friends got caught stealing watermelons and their fathers forced them to eat them all, and the initiation ritual in his neighborhood that involved sending a new boy running through the sewage pipes, and the time, early in their marriage, when our nearsighted mother--who, like a lot of women of the time, tried not to wear her glasses unless she absolutely had to, out of a kind of vanity--was responsible for their driving onto the runway at Friendship International Airport. In retrospect, I see those were all cautionary tales, but the important thing at the time was the great pleasure my father took in telling them. He had a darker side that we got to see fairly often; stories could make him and us laugh, so they were valuable currency, something to cherish.

Give readers an example of a story or book that you really love, one that has a puzzle, mystery or magic in its core.

Puzzles: Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita. Mystery: Graham Greene's The Quiet American. Magic: William Goldman's The Princess Bride.

But here's the point: Every story, novel and poem I love has mystery and magic at its core.

--Matthew Tiffany, LCPC, writer for Condalmo and psychotherapist

Peter Turchi: Puzzling Out Writing

A month ago, still on an islands kick, we went to Jersey and Guernsey, and realized that we were only a ferry ride away from Saint-Malo, the setting for possibly the best book of the year, All the Light We Cannot See. What luck! Almost as if we had planned it (we are never that organized). Arriving after dark, we had to walk from the dock to the walled town; once there, we immediately got lost in the winding, narrow streets. It was a perfect immersion into the magic of the book and the town. The next morning, walking the ramparts in the heavy wind, with ocean waves crashing, we were pretty darned happy. (And beautiful Guernsey--I must reread The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.) --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

A month ago, still on an islands kick, we went to Jersey and Guernsey, and realized that we were only a ferry ride away from Saint-Malo, the setting for possibly the best book of the year, All the Light We Cannot See. What luck! Almost as if we had planned it (we are never that organized). Arriving after dark, we had to walk from the dock to the walled town; once there, we immediately got lost in the winding, narrow streets. It was a perfect immersion into the magic of the book and the town. The next morning, walking the ramparts in the heavy wind, with ocean waves crashing, we were pretty darned happy. (And beautiful Guernsey--I must reread The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.) --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

In addition to puzzles, you touch on magic and magicians. "Magician" can refer to a fantasy-world wizard or to the David Copperfield type of magic, where the practitioner uses slight-of-hand and deception to fool the audience. Which "magic" has more potency for writers?

In addition to puzzles, you touch on magic and magicians. "Magician" can refer to a fantasy-world wizard or to the David Copperfield type of magic, where the practitioner uses slight-of-hand and deception to fool the audience. Which "magic" has more potency for writers? Many people consider Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy the greatest novel of all time; others say it's the greatest soap opera of all time. Perhaps it's both--such is the storytelling power of the book and the range of fascinating characters, from the doomed Anna to earnest, down-to-earth Levin to the swaggering Vronsky. With perhaps the best known first line in literature--"All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way"--the novel first appeared in book form in Russia in 1878. It's a testament to its popularity that it has been translated into English multiple times. Constance Garnett's 1901 translation, updated in 1965, although criticized by some, is excellent for those who want a suitably archaic feel to the text. Among more recent translations are the Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky version of 2000, published here by Viking and Penguin and beloved by many. And this month, Yale University Press is publishing yet another translation, by Marian Schwartz, in its Margellos series. In whatever version, this sweeping tale is highly recommended--by Oprah, too, who chose it for her book club in 2004!

Many people consider Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy the greatest novel of all time; others say it's the greatest soap opera of all time. Perhaps it's both--such is the storytelling power of the book and the range of fascinating characters, from the doomed Anna to earnest, down-to-earth Levin to the swaggering Vronsky. With perhaps the best known first line in literature--"All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way"--the novel first appeared in book form in Russia in 1878. It's a testament to its popularity that it has been translated into English multiple times. Constance Garnett's 1901 translation, updated in 1965, although criticized by some, is excellent for those who want a suitably archaic feel to the text. Among more recent translations are the Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky version of 2000, published here by Viking and Penguin and beloved by many. And this month, Yale University Press is publishing yet another translation, by Marian Schwartz, in its Margellos series. In whatever version, this sweeping tale is highly recommended--by Oprah, too, who chose it for her book club in 2004!